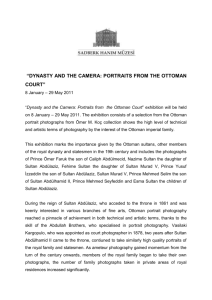

Sultan Abdülhamid II and Palestine: Private lands and imperial policy

advertisement