Rethinking Allison's Models

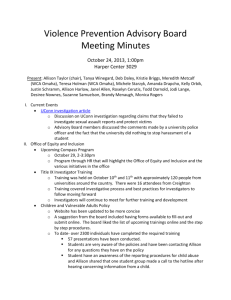

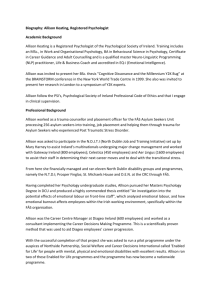

advertisement