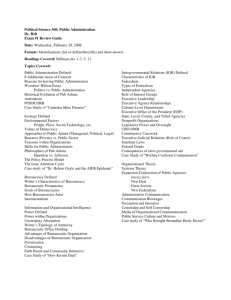

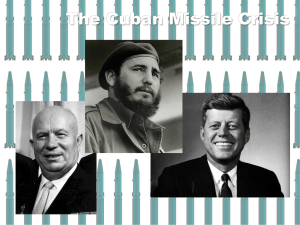

The Organizational Process and Bureaucratic Politics Paradigms

advertisement