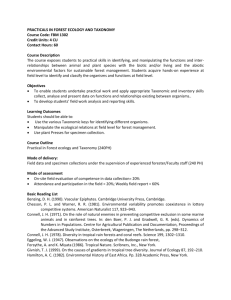

Global Ecological Forest Classification and Forest Protected Area

advertisement