Encounters with Jane Tompkins

advertisement

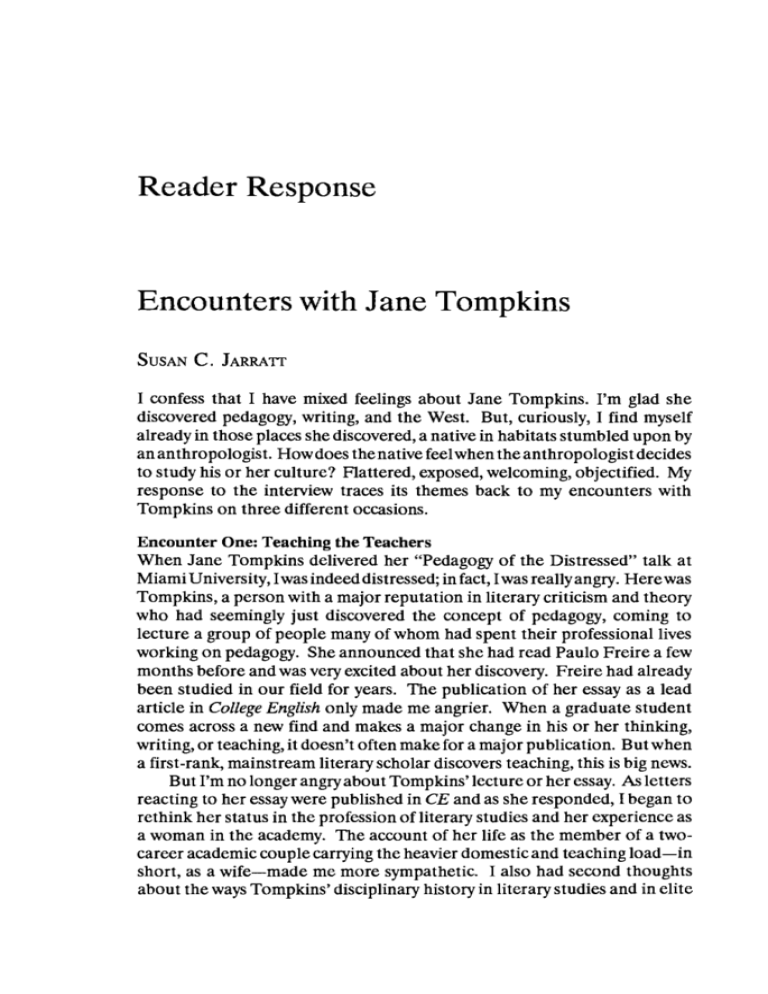

Reader Response Encounters with Jane Tompkins SUSAN C. JARRAIT I confess that I have mixed feelings about Jane Tompkins. I'm glad she discovered pedagogy, writing, and the West. But, curiously, I find myself already in those places she discovered, a native in habitats stumbled upon by an anthropologist. How does the native feel when the anthropologist decides to study his or her culture? Flattered, exposed, welcoming, objectified. My response to the interview traces its themes back to my encounters with Tompkins on three different occasions. Encounter One: Teaching the Teachers When Jane Tompkins delivered her "Pedagogy of the Distressed" talk at Miami University, I was indeed distressed; in fact, I was really angry. Here was Tompkins, a person with a major reputation in literary criticism and theory who had seemingly just discovered the concept of pedagogy, coming to lecture a group of people many of whom had spent their professional lives working on pedagogy. She announced that she had read Paulo Freire a few months before and was very excited about her discovery. Freire had already been studied in our field for years. The publication of her essay as a lead article in College English only made me angrier. When a graduate student comes across a new find and makes a major change in his or her thinking, writing, or teaching, it doesn't often make for a major publication. But when a first-rank, mainstream literary scholar discovers teaching, this is big news. But I'm no longer angry about Tompkins' lecture or her essay. As letters reacting to her essay were published in CE and as she responded, I began to rethink her status in the profession of literary studies and her experience as a woman in the academy. The account of her life as the member of a twocareer academic couple carrying the heavier domestic and teaChing load-in short, as a wife-made me more sympathetic. I also had second thoughts about the ways Tompkins' disciplinary history in literary studies and in elite 352 JAC universities kept her at a distance from composition as a discipline. These changes, however, didn't affect my puzzlement about her lack of study in our field before she made her pronouncements. One of the letters of response to her article, after praising her, gently informed Tompkins of the twenty-fiveyear existence of NCTE. This was a lack Tompkins might have remedied in the years following her entry into the domain of composition, but, unfortunately, the anthropological stance persists in theJAC interview. Tompkins' claim to a fifteen-year history as a writing instructor does not lead herto identify herself with "people who do that day to day"; she's still an outsider by choice. Though Tompkins feels "indebted" to people working in the field and acknowledges good work about writing pedagogy, she doesn't yet have many thoughts about the disCipline, claiming that her pedagogy involves "no methods at all." While having read Elbow on writing groups influences her own writing practice, Tompkins doesn't speak about applying Elbow's ideas in her own classroom. Not being trained in the discipline is a handicap impressively overcome by many first-generation rhetoric and composition scholars, including Lisa Ede and Elizabeth Flynn. Compositionists would have expected Tompkins, more than the other major scholars in philosophy, linguistics, and literary theory featured in these interviews, to have done some homework in the field, especially given the fact that she's writing a book about pedagogy. Though I'm no longer angry, I'm disappointed at her continuing distance from composition studies. In this interview, her response to the field remains primarily at the level offeelings rather than intellectual or scholarly engagement. If she were reading in the field, Tompkins would find her current ideas about Freirean-style pedagogy moving in the same direction as others who attempted at one time a direct imitation of Freire's democratization methods but now see the need for adaptation. We are now listening to what Freire has said about differences in contexts, observing that the needs and positions of U.S. students-their literacies-are different from those of Freire's students. The next stage in critical pedagogy will attend to a double agenda: encouragingstudents to take responsibility, as Tompkins suggests, for their education, along with recognizing the need for knowledge eXChange-knowledge about how language works dialogically, and about material and social conditions for the production of discourse in various cultural contexts. Critical pedagogues like Henry Giroux, Ira Shor, and Kathleen Weiler have moved in this direction, but there is a great need for feminists and others associated with social movements in the U.S. to articulate responses to this Challenge. I found myself speculating about how the new book on pedagogy might weigh in on this issue. We might take a clue from Tompkins' idea about performance. Tompkins describes traditional teaching as performance, with the teacher exercising authority and delivering information. In moving away from that mode, Tompkins implies she is no longer a performer, only herself. This understanding of performance differs from some current feminist readings of Reader Response 353 subjectivity in general, and gender in particular, as performances (for example, see Bizzell and Butler). The idea is that everyone is performing a self, a gender, all the time, and that institutional positions such as teacher and student are always performances as well, with a range of possible choices about how to carry out those performances. On this analysis, Tompkins chooses not her real self over a performing self, but rather changes the kind of performance to one that allows for more emotion in the classroom. Opening the classroom to emotion and personal experience is a tactic endorsed by teachers from a number of positions: certain feminisms, cultural studies, critical pedagogy, andexpressivist composition. But this tactic serves different ends in these different contexts. In service of what political project can we see Tompkins' "liberatory" teaching, then? When she speaks of getting students to take responsibility, Tompkins sounds somewhat like advocates of critical pedagogy. But her characterizations of students and of the act of writing suggest different alignments. Tompkins focuses on the experiences of "the individuals who happen to be in the room" -single collections of life-experience presumably undifferentiated by social factors such as class, race, gender. Further, Tompkins' way of talking about writing as self-discovery casts her as the subject of expressivist pedagogy: a writer on an internal journey. In the comparison of writing with therapy, she sounds much like Elbow, advocating writing as "self-development, self-discovery." Though I don't share this view of composition theory, I respect those who advance strong and serious arguments for it. But Tompkins' further comments in this vein, references to writing as grooming, like "getting a massage orworkingout," seem to trivialize the focus on the individual, making writing sound like a yuppie pastime. Much ink has been shed in the arguments about expressive versus social constructionist theories of writing. As with many important debates, much rides on the definitions of its terms. Not only does Tompkins seem unaware ofthose debates in composition theory, she seems to be several stages behind that dialogue in her treatment of the writing subject so unproblematically as a given, "natural" self. I feel quite certain that Tompkins is very aware of current theories of subjectivity but is purposely avoiding them-to be accessible, to try to cut through an alienating theoretical language, to reposition herself and her writing in the academy. Tompkins' career trajectory leads her away from theory in general; she wants now to uncomplicate and merge personal and academic, home and school. While I respect a personal decision made at some profeSSional risk in an exposed public arena, in my view, Tompkins' stance is not the most productive one for composition studies now. The most exciting advances in arguments about composition and literary studies are coming out of current work in feminist theory and cultural studies, places where "experience" and "self' are both valued and analyzed. Especially given the current work exposing the negative feminization of composition, turning for answers to key questions in composition theory 354 lAC toward an unmediated experience of the personal, strongly associated with the feminine, is a bad idea. Encounter Two: Feminism, or How Political Is the Personal? When I picked up the issue of New Literary History centered on feminist epistemology, it was with an uneasy feeling. Already knowing I had major intellectual objections to the key essay, I placed myself in the positions of the feminists who were asked to respond. How would I have handled such a task? How would I have negotiated my conflicting desires to argue, critique, even displace the feminist author's views with my own and to preserve solidarity among feminists, a marginal group in academic knowledge-production? Tompkins' response to the situation struck me as perfect. She acknowledged the difficulty, responded to the author as an academic woman in a maledominated field, while at the same time encasing a cri tiq ue ofthe essay wi thin her response. Her creative approach to the task exemplifies critique in the strong sense: respectful, engaged, and committed. I often include her essay, "Me and My Shadow," on reading lists for graduate seminars, and it surprised me the first time female graduate students reacted with anger and resentment to it. They said, "Tompkins has the leisure, the freedom to respond in such a relaxed way because of her status. If one of us tried to write such a piece, it would never be published." Tompkins addresses the complaint in the lAC interview effectively. Should she not move into a personal mode because it is possible for her to do so and not for others? No. The more interesting question is how she deploys the personal, the autobiographical: what kind of personal self she creates or performs. As in her remarks about the function of writing, Tompkins keeps alive the idea of a self uncovered, discovered. In the questions about deconstructive writing and the reference to Cixous, there was an opportunity to refigure the relation of writing to "self," but instead "self' gets collapsed back into "self-creation" without any exploration of text or performance in deconstruction. One self Tompkins was neither confessing nor professing in this interview was the feminist. Throughout the interview Tompkins resists identifying her practice with feminism, which she seems to eq ua te with "female." The text is full of qualifications of the term: her teaching is "historically feminist, or by circumstances feminist"; the current relationship between the personal and the academic is for Tompkins "de facto feminist." In many moments, the evocation of feminism suggests to Tompkins the exclusion of men; to be "feminist" is to be "cordoned off." Again, this response can be placed in her own personal history. Her relation to the academy features competition and "personal injury," to which she responded by attacking the "male critical establishment." As Tompkins recreates that history and its present for herself, she implicitly associates feminism with that attack, but she then Reader Response 355 implies that softening it, moving away from it as she is now, requires moving away from feminism. The most telling moment ofthis limited definition offeminism comes in her response to the question about a need for a specifically "female-oriented radical pedagogy." Tompkins speculates that a "specifically feminist pedagogy" would be needed in specific circumstances. The example she gives is a literacy program for pregnant women in North Carolina. Only "other" women need feminism? The implication here is that feminism is a benevolent, philanthropic enterprise aimed at a group of ''women'' in reduced circumstances. This is a reform, nota trans formative feminism: a matronizing (rather than patronizing) gesture which fails to acknowledge the larger structures of gender power, the possibility that patriarchy affects women and men in every class and in every classroom. This interview creates an odd picture of feminism, the political movement and intellectual operation within which Tompkins' life and work make sense. At times it seemed that Tompkins defines feminism as many of my undergraduates do: an aggressive, woman-promoting, male-deriding, inyour-face movement that has nothing to do with them, that wishes only to exclude men. Certainly, there are feminists and feminisms that fit that description. But so many of the ideas and plans Tompkins presents in the interview and in her work-the critique of Westerns as misogynist, the need to reconnect the personal and academic, the need for understanding students and teachers as whole people with emotional and material existences as well as intellectual-all these projects have deeply feminist connections. That Tompkins is silent on those and offers in place only an interest in the responsibility or pain of the individual throws her comments by default into a liberal theory of democracy in which people are individuals with separate emotions and lives and with responsibilities within a social contract system. This stance is disappointing and not consistent with the Freirean source. Despite Tompkins' attempt to distance herself from the epistemology of her husband, she speaks more to an audience of potentially hostile men than to feminists or even other women. At moments, Tompkins aligns the genders in a more productive way. Her remarks about a men's movement suggest a relational change and note potential problems with this particular men's movement. I also appreciated her response to the question of Freire and sexism. It's too easy to ignore Freire's intellectual history and context, to pick up on the exclusive language and dismiss the conceptual and liberatory power of his work. Encounter Three: Beautiful Blue Eyes Jane Tompkins came to Miami University again, this time to talk about Buffalo Bill. As a native Texan, I once again felt "discovered." She suggested that her visit to a museum in Wyoming constituted an unmediated encounter with "the West"; it was an attempt to cut through the layers of aggrandize- 356 JAC ment and reaction by confronting Bill face to face. Ergo the eyes, noted in the Lawrence Ferlinghetti poem she distributed with the lecture. I thought about buffalo eyes-those wild and totally guileless marbles offear. Because you only see them in movies as the camera gets close when they're about to get killed. I also thought about all the pairs of cunning blue eyes I've seen under the brims of cowboy hats in kicker bars. Picture Harlin in Thelma and Louise. There's no innocently cutting through that Western, male ethos, descended directly from B.B. Cody. I think about the boy in my brother's high school class who had a beautiful eye (color unknown) kicked out by a cowboy boot in a totally typical little brawl one night. I didn't need to go to a museum to encounter "the West." But then Tompkins knows all this. That's why my reactions are mixed. I was puzzled by the questions on West ofEverything. What better to do with Westerns than put our best critical energies into exploring their violence and misogyny? I also wondered about the question on animal rights. Why not talk about Indians instead of animals, especially in 1992? The "Indians" chapter has been anthologized for writing classes and written about by at least one compositionist (Schilb). Tompkins anticipated the sharp focus on Native Americans this year, examining the way knowledge is created. Through writing this response I discovered that Jane Tompkins likes to discover things and that I don't like to feel "discovered." Writing this response wasn't much like massage. It felt more like scraping a pumice stone over rough and calloused skin-callouses that protect, skin that gets red and painful. Miami University Oxford, Ohio Works Cited Bizzell, Patricia. "The Praise of Folly, The Woman Rhetor, and Post-Modern Skepticism." Rhetoric Society Quarterly 22.1 (Winter 1992): 7-17. Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble. Feminism and the Subversion ofIdentity. New York: Routledge, 1990. Schilb, John. "The Role of Ethos: Ethics, Rhetoric, and Politics in Contemporary Feminist Theory." PRE/TTEXT11 (1990): 211-34.