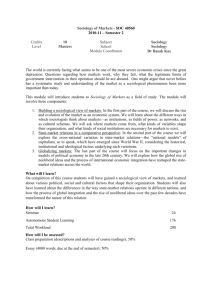

Sociological Understandings of Conduct for a Noncanonical Activity

advertisement