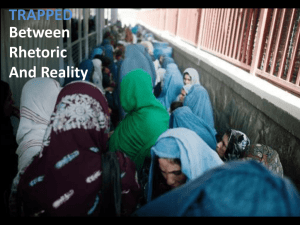

Civilians Under Fire - Doctors Without Borders

advertisement