Interagency Collaboration: a review of the literature

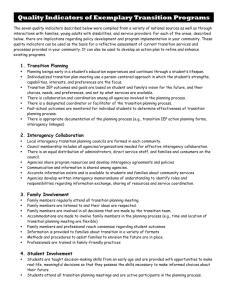

advertisement