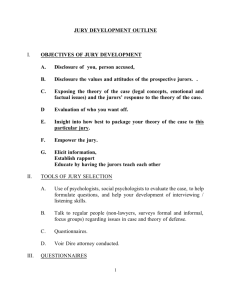

Voir Dire: Questioning Prospective Jurors

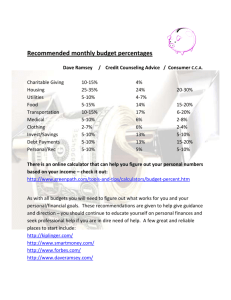

advertisement