Gen. Char. of Baroque Music

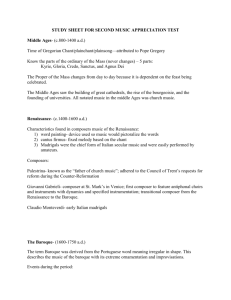

advertisement

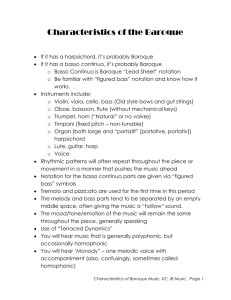

General Characteristics of Baroque Music Unity of Mood: Baroque music is famous for its “doctrine of affections (or mood).” What is happy will be happy throughout and what is sad continues to the end. Composers molded the musical language to fit moods and affections. Some definite rhythms and melodic patterns are used to define certain moods and expressions. The prime exception to this baroque principle of unity of mood occurs in vocal music in which the text contains drastic changes of emotion. These changes inspire corresponding changes in the music. But even in such cases, the given mood will continue for quite some time before it changes to another. Rhythm: Unity of mood in baroque is first conveyed by the continuity of rhythm. Rhythmic patterns heard at the beginning of the piece are reiterated many times throughout. This relentless drive gives the music forward motion. This forward motion is hardly ever interrupted. The sense of beat or pulse is also far more distinct in baroque music, especially baroque instrumental music. Melody: Baroque music creates a feeling of continuity. An opening melody will be heard over and over again in the course of the piece. Even if the character of the piece is constant, the passage is varied. Many baroque melodies are complex and elaborate. They are not easy to sing or play. Baroque melodies give and impression of dynamic expansion rather than balance and symmetry. This dynamically expanding melody is described by the German term “Fortspinnung.” Terraced Dynamics: Paralleling the continuity of mood, the dynamics of a piece (i.e., the relative softness or loudness of the music) also stays constant for some period of time before shifting to another level. When the dynamics shift, it is sudden like physically stepping up or down a step. Therefore, terraced dynamics are a distinctive quality of baroque music. Gradual changes such as crescendos and decrescendos are unheard due in part to the capabilities of the keyboard instruments of the time. For instance, when the stops are activated on the pipe organ, they are either “on” or “off,” and cannot be gradually turned on or off. Texture*: The favored texture in baroque composition varies from early to late baroque. Early baroque music tends to be homophonic as composer reacted against the highly schooled polyphonic textures predominant in the Renaissance, and as operatic composers explored the freer rhythms of spoken language. Late baroque music, the kind most often heard today, is predominantly polyphonic in texture. Soprano and Bass lines are often set in opposition to each other and are often more important than the interior lines. Nevertheless, imitation between various lines is very common. While polyphony was the dominant texture in the late baroque, short snatches of homophonic texture often occur in Handel’s music and, more rarely, in Bach’s music. Basso continuo and figured bass: In any baroque piece, it is common to see in the printed music various numerals below the bass line. These figures represent a type of shorthand notation that told the keyboardist which chords to play in the accompaniment. In baroque music, the bass line is performed by two instrumentalists—1) a sustaining bass instrument such as the cello to play the actual bass notes, and 2) a keyboard player (harpsichord or organ) who improvised the accompaniment based on the figures. Words and Music In vocal music, baroque composers were motivated to provide in their music a faithful representation of the text. Often this representation involved the use of “word painting.” In word painting, significant words in the text are given special treatment in the melodic line. An example might be a rising line on the words, “heaven” or “sky,” and a descending line on the words, “valley,” “hell,” or the “abyss.” *Texture in music refers to the number of melodic lines present at any given moment and how these lines relate to each other. Monophonic Texture consists of a single melodic line with no harmony or other accompaniment. Homophonic Texture consists of a single harmonic line supported by harmony. In Polyphonic Texture more than one melodic line competes for the listener’s attention. General Principles of Baroque Composition Unifying Principles (i.e., “ordering principles”) 1. Unity of Rhythm 2. Unity of Mood 3. Organic repetition of musical ideas—rhythmic and melodic 4. Tonality (major-minor) and the harmonic structure Contrasting Principles 1. Polarization of the Soprano and Bass Lines 2. Contrast---between bodies of sound, between loud and soft, etc. 3. Polyphonic texture (i.e., two or more melodies sounding simultaneously).