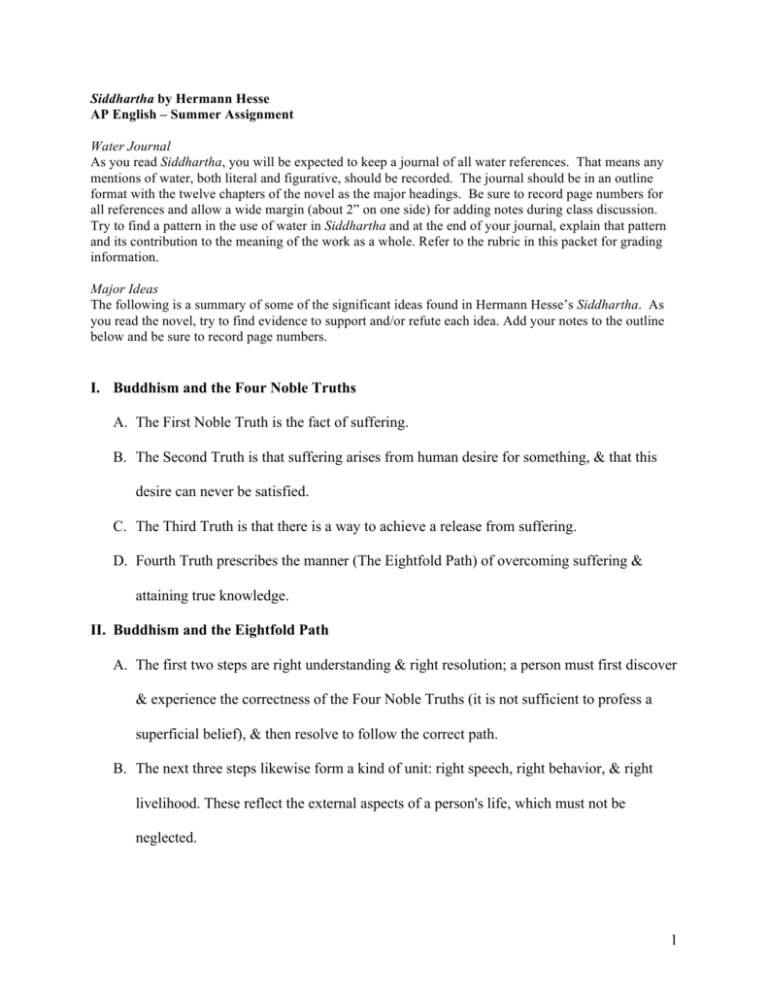

Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse

AP English – Summer Assignment

Water Journal

As you read Siddhartha, you will be expected to keep a journal of all water references. That means any

mentions of water, both literal and figurative, should be recorded. The journal should be in an outline

format with the twelve chapters of the novel as the major headings. Be sure to record page numbers for

all references and allow a wide margin (about 2” on one side) for adding notes during class discussion.

Try to find a pattern in the use of water in Siddhartha and at the end of your journal, explain that pattern

and its contribution to the meaning of the work as a whole. Refer to the rubric in this packet for grading

information.

Major Ideas

The following is a summary of some of the significant ideas found in Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha. As

you read the novel, try to find evidence to support and/or refute each idea. Add your notes to the outline

below and be sure to record page numbers.

I. Buddhism and the Four Noble Truths

A. The First Noble Truth is the fact of suffering.

B. The Second Truth is that suffering arises from human desire for something, & that this

desire can never be satisfied.

C. The Third Truth is that there is a way to achieve a release from suffering.

D. Fourth Truth prescribes the manner (The Eightfold Path) of overcoming suffering &

attaining true knowledge.

II. Buddhism and the Eightfold Path

A. The first two steps are right understanding & right resolution; a person must first discover

& experience the correctness of the Four Noble Truths (it is not sufficient to profess a

superficial belief), & then resolve to follow the correct path.

B. The next three steps likewise form a kind of unit: right speech, right behavior, & right

livelihood. These reflect the external aspects of a person's life, which must not be

neglected.

1

C. The interior disciplines constitute the final three steps: right efforts, right mindfulness,

and right contemplation. By this means, the follower of Buddha can arrive at Nirvana.

III. Siddhartha and Hinduism

A. The basic central problems of Siddhartha and the Bhagavad Gita, an important poetical

document of the Hindu religion, are similar: how can the hero attain a state of total

happiness and serenity by means of a long and arduous path?

B. Stages of hero development in the Bhagavad Gita

1. Action: produced by acceptance of the Divine element in an individual

2. Knowledge: knowledge of the Self and of the Absolute, which ultimately are

revealed to be identical

3. Wisdom: The seeker reveres and even worships the Absolute, with which he is

identical

4. Seeker must find his own path; the Quest for Truth is important.

IV. Stages of hero development in Hesse’s works (incl. Siddhartha)

A. Innocence

B. knowledge ("sin")

C. together, these lead to a higher state of innocence accompanied by increased awareness &

consciousness

V. Christian elements in Siddhartha

A. Importance of love

B. Protestant character; i.e. faith alone leads to salvation

C. Presumably good works follow from faith

D. Forms and rituals are empty

2

Hermann Hesse

Hermann Hesse (1877-1962), German poet and novelist, who has depicted in his works the duality of

spirit and nature, body versus mind and the individual's spiritual search outside the restrictions of the

society. Hesse was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1946.

Hermann Hesse was born into a family of Pietist missionaries and religious publishers in the Black Forest

town of Calw, in the German state of Wüttenberg on July 2, 1877. His parents expected him to follow the

family tradition in theology. Hesse entered the Protestant seminary at Maulbronn in 1891, but he was

expelled from the school. After unhappy experiences at a secular school, Hesse worked in several jobs.

In 1899 Hesse published his first works, Romantische Lieder and Eine Stunde Hinter Mitternacht. Hesse

became a freelance writer in 1904, when his novel Peter Camenzind gained literary success. The book

reflected Hesse's disgust with the educational system. In the same year he married Maria Bernoulli, with

whom he had three children. A visit to India in 1911 interested Hesse in studies of Eastern religions and

culminated in the novel Siddhartha (1922). It was based on the early life of Gautama Buddha. The culture

of the ancient Hindus and the ancient Chinese had a great influence on Hesse's works.

In 1912 Hesse and his family took a permanent residence in Switzerland. In the novel Rosshalde (1914)

Hesse explored the question of whether the artist should marry. The author's reply was negative. During

these years his wife suffered from growing mental instability and his son was seriously ill. Hesse spent

the years of World War I in Switzerland, attacking the prevailing moods of militarism and nationalism.

Hesse's breakthrough novel was Demian (1919). It was a Faustian tale of a man torn between his orderly

bourgeois existence and a chaotic world of sensuality.

Leaving his family in 1919, Hesse moved to Montagnola, in southern Switzerland. In 1922 appeared

Siddhartha, a novel of asceticism set in the time of Buddha. Its English translation in the 1950s became a

spiritual guide to the generation of American Beat poets. Hesse's second marriage to Ruth Wenger (192427) was unhappy. These difficult years produced Der Steppenwolf(1927). During the Weimar Republic

(1919-1933) Hesse stayed aloof from politics.

In 1931 Hesse married his third wife, Ninon Dolbin, and began in the same year work on his masterpiece

Das Glasperlenspiel, which was published in 1943. In 1942 Hesse sent the manuscript to Berlin for

3

publication. It was not accepted by the Nazis and the work appeared for the first time in Zürich. . Hesse's

other central works include In Sight of Chaos (1923), a collection of essays, the novel Narcissus and

Goldmund (1930) and Poems (1970).

After receiving the Nobel Prize Hesse wrote no major works. He died of cerebral hemorrhage in his sleep

on August 9, 1962 at the age of eighty-five. He is still one of the best-selling German writers throughout

the world.

“Hermann Hesse.” The Literature Network. Available: http://www.online-literature.com/hesse/.

Accessed: 2 December 2003.

And if you are caught without your book, access the novel online here: http://www.onlineliterature.com/hesse/siddhartha/

4

Works of Hermann Hesse: Composition, Publication, And Translation Of Siddhartha

( Monarch Notes ) Hesse, Hermann; 01-01-1963

Genesis and publication

Siddhartha was begun in 1919, when Hesse was enjoying one of his most happy and productive

periods. He quickly finished the first four chapters and published them in a periodical. He turned then to

other projects (including the story Klingsor's Last Summer), and resumed work on Siddhartha later in the

winter of 1919-1920. He completed the second portion, consisting of chapters five through eight, and then

found himself unable to complete his story.

Hesse recorded his thoughts from these months in a diary which he published in 1932, in the

German periodical Corona. In this diary, Hesse speaks of many things, especially of his feeling of

loneliness and isolation and his inability to work. He is depressed by the many letters which he is

receiving from Germans who rebuke him for his lack of patriotism for his native land during the recent

war. He calls 1920 the "most unproductive year" of his life, and exclaims, "Oh, how I wish I were able to

work" Siddhartha, specifically, is a problem. As long as he was depicting Siddhartha's seeking, learning,

suffering, and errors, he was able to proceed without difficulty. But now that it is time to portray the

triumphant Siddhartha, he finds that it is impossible to go on.

In several lengthy and highly interesting passages, Hesse discusses the development of his

interest in Indian thought, and his changing ideas on this important subject. Although he has been

studying India intensively for some twenty years, only recently has his interest extended beyond

philosophy to narrower questions of religion and theology. Buddhism, especially, has attracted his

attention and he sees in it a relationship to Christian Protestantism. Hesse also comments on the figure of

the Buddha, to some extent echoing Siddhartha's sentiments. Although Buddha undoubtedly did attain

Nirvana, Hesse says, modern man cannot follow his path - each man must rather find his own way to his

own goal.

In the course of the published "diary" fragment - which is actually a polished, if highly personal,

essay - Hesse states that he is overcoming his period of inactivity, and the final words are: "Siddhartha is

once again present. Things are moving forward." He did soon complete the novel and it was published in

its entirety in 1992 under the title Siddhartha: An Indic Poetic Work.

Translation

An English version by Silda Rosner appeared in 1951. This translation has been reprinted many

times, and was for some years the most popular of Hesse's works in English. Like all of Hesse's novels, it

is currently available in this country in paperback. Although not without weaknesses (no translation, it

should be pointed out, is ever entirely without weaknesses), this is an entirely satisfactory and faithful

rendering of Hesse's novel in both style and content.

Explanation Of Selected Eastern Terminology

Atman: a complicated Sanskrit term which has many meanings: breath, the self, the Universal Self.

Brahma: the Lord of Creation.

Brahman: 1) the Central Power of the universe; 2) (also spelled "Brahmin") a member of the highest of

the four Hindu classes. Typically a Brahman, such as Siddhartha's father, is an erudite man who

studies and teaches the scriptures and performs religious ceremonies.

Jetavana: historically, a garden, one of the residences of Gotama, the Buddha.

Kama: the Hindu god of desire.

5

Krishna: one of the most famous incarnations of Vishnu, the Preserver, in Hindu theology.

Lakshmi: the Hindu goddess of beauty and good fortune.

Magadha: an important kingdom in ancient India.

Mara: in Buddhist theology, the spirit of evil and enemy of the Buddha.

Maya: illusion.

Nirvana: in Buddhism, a state, extremely difficult to define (or to attain!) characterized by a release from

the bonds of suffering.

Om: defined in the novel as "Perfection" (in the chapter "By the River").

Prajapati: Creator or Supreme Deity.

Sakya: a clan name of Gotama the Buddha.

Samana: a mendicant ascetic.

Samsara: the world characterized by endless repetition, without Nirvana.

Satyam: Truth and Reality.

Upanishads: mystical utterances at the conclusion of the Vedas.

Vedas: ancient scriptural literature of Hinduism.

Vishnu: the Preserver, a major Hindu deity.

Hesse And India

India had long fascinated the romantically-inclined Germans. Many of the poets of German

Romanticism were interested in India as well as in other Eastern cultures, and Goethe shared this interest.

The Indic tradition in German literature remained alive during the nineteenth century, and a number of

authors of that period translated or imitated works from Indian literature. Hesse was familiar with much

of this long and rich tradition.

Hesse's own family background provided a specific link to India. Both of his parents had lived as

missionaries in India and had grown familiar with the culture of that land. His grandfather had likewise

been a missionary in India, and was quite knowledgeable in the area of Indian philosophy and theology,

as was Hesse's own father. Both men amassed impressive collections of books on the subject. Hermann

accordingly had access to the mysteries of India from several sources. Early in his childhood he acquired

a keen interest in the East, an interest which he was never to lose.

Shortly after 1900, Hesse began the serious study of Indian culture. His interest deepened, and as

the years passed he fabricated an idealized image of this distant land. As his own personal problems grew

more acute, he came to think of India as a land of salvation. In 1991 he undertook a voyage to India,

seeking peace and happiness. In a sense his voyage was a failure. Hesse was not able to apply India's

magic to his own situation and his specific personal problems were not solved. But on a higher level his

voyage did prove to be a success. While in India Hesse came to believe in "Oneness," "Harmony," or

whatever this mysterious aspect of Indian thought might be called in Western languages which have no

adequate terminology for it. Hesse began to search for a means of symbolically expressing this feeling

and finally, after much labor and anguish, was able to find this expression in Siddhartha.

Hesse's interest in India did not cease with the publication of Siddhartha. The East is important in

several of the later works, especially, of course, in Journey to the East, but also in The Glass Bead Game.

6

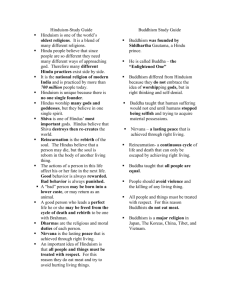

Hinduism

( The 1998 Canadian Encyclopedia ) DAVID J. GOA AND HAROLD G. COWARD; 09-06-1997

Hinduism, the religion of about 400 million people in India, Africa, Indonesia and the West Indies.

Immigration from these countries (principally India) to Canada has provided the base for a Canadian

population of about 120,500 Hindus (1991c, the last figures available). Evidence of the existence of

Hinduism dates back 4000 years. It reached a stage of high philosophical, religious and psychological

development by 1500 BC and has sustained it to the present.

Supremacy in India

Hinduism has maintained its supremacy in India despite numerous migrations into the country and

attempts at evangelization by other religions; notably, BUDDHISM, ISLAM and CHRISTIANITY.

Hindu culture and religion possess a unique vitality which has enabled Hinduism to become the

foundation of the religions practised by over half the world's population. People in China, Japan, Tibet,

Burma [Myanmar], Thailand and Ceylon [Sri Lanka] all look to India as their ancestral spiritual home.

Uniqueness of Hindu World

For the Hindu, God is the one supreme universal spirit that underlies all human, animal and material life,

and towards which all religious feelings and theology strive. To Hindus each religion's and every

devotee's particular picture of God represents a true aspect of God. But the uniqueness of the Hindu world

view centres on 4 important concepts: anadi (beginninglessness), karma (the moral law of life), samsara

(rebirth) and moksha (freedom or release). The basic Indian world view assumes a cycle of birth, death

and rebirth leading the believer to the desire for release from this endless round of suffering "suffering,"

because life in this world implies separation from the divine.

Cycles of Creation

Hindu thought has no concept for the creation of the universe, assuming that everything the universe,

God, scripture and humanity has existed without beginning. Within this view is the idea of cycles of

creation with relative beginnings. Each cycle begins from a pre-existent seed state, grows, flowers,

withers and dies. But, just as a dying flower leaves seeds for its own propagation, each cycle drops a seed

which begins the next state.

Destiny

In Hindu belief, the universe we are now experiencing is in one such relative cycle of creation. A

consequence of this view is typified in the term "karma." Each person is responsible for his or her own

destiny. If one performs good actions and thinks good thoughts, this will establish the probability of a

good future even in the next cycle of creation. The doctrine of karma teaches that when a person acts or

thinks, a memory trace or seed laid in the unconscious will predispose the individual to that same kind of

action or thought in the future. Each person is reborn (reincarnated) again and again, according to his or

her karma.

Doctrine of Reincarnation

Many of the thoughts and desires we find when we analyse our unconscious impulses come from

thoughts and actions of previous lives. What we experience in this life is in part a consequence of all the

good and bad actions and thoughts of previous lives. The doctrine of reincarnation is manifested in

society by the caste system, which has 4 levels at which an individual may be reborn, according to the

karmic merit accumulated: brahman (priest or teacher), kshatriya (warrior or politician), vaishya

(merchant or professional) and sudra (servant or labourer). Long after these categories were established,

some sudras became known as untouchables, or "outcastes."

7

Reaching the Level of the Gods

The karmic balance in the unconscious at the time of death determines the state or level at which a person

will be reborn. Through countless lives one can spiral upwards, finally to reach the level of the gods.

There the individual experiences the honour of sitting in the place of a deity, exercising the deity's cosmic

function until the good merit is exhausted. If through evil living one is reborn as an animal, he will simply

follow his instincts and experience the suffering that such instincts produce. Such is the cycle of rebirth,

"samsara." How to find a way out of this cycle is an important question in Hinduism and Buddhism. The

Hindu answer is called "moksha."

Moksha

“Moksha” is release from the merry-go-round of birth, death and rebirth. The 3 ways of obtaining release

are the yoga of knowledge, the yoga of action and the yoga of devotion. The yoga of knowledge involves

intellectual and psychological techniques developed by Hindu holy men to control their actions and

analyse their unconscious. They remove the karmic obstructions of previous lives, recovering the nature

of their true selves. The true self is shown to be nothing other than Brahman, or God. The goal of all

knowledge, therefore, is the experience of union with the divine.

The yoga of action requires that duty be done with no thought for oneself or for the benefit or suffering

that one experiences in fulfilling it. Through the performance of one's duty as a dedication to the Lord, a

kind of inner purification takes place, resulting in divine union. The yoga of devotion, the most common

path, requires that prayers, the chanting of scripture and meditation on the image of the Lord be

undertaken with such intensity that inner karmic obstructions are burned up and the Lord is revealed

within consciousness. All that is required is willingness to surrender oneself completely in devotion to

God. Regardless of which path is followed, the end is the same: the discovery of the true nature within

oneself of a spiritual soul (atman) which is at one with God.

The 1998 Canadian Encyclopedia copyright ©1998 by McClelland & Stewart, Inc. All rights reserved. Any

commercial use is strictly forbidden.

DAVID J. GOA AND HAROLD G. COWARD, Hinduism. , The 1998 Canadian Encyclopedia, 09-06-1997.

*********************************************

Hinduism (hin´dOOizum)

( The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition ) ; 01-01-1993

Hinduism (hin´dOOizum)

Western term for the religious beliefs and practices of the vast majority of the people of India. One of the

oldest living religions in the world, Hinduism is unique among the world religions in that it had no single

founder but grew over a period of 4,000 years in syncretism with the religious and cultural movements of

the Indian subcontinent. Hinduism is composed of innumerable sects and has no well-defined

ecclesiastical organization. Its two most general features are the caste system and acceptance of the Veda

as the most sacred scriptures.

Early Hinduism

Hinduism is a synthesis of the religion brought into India by the Aryans (c.1500 B.C.) and indigenous

religion. The first phase of Hinduism was early Brahmanism, the religion of the priests or Brahmans who

performed the Vedic sacrifice, through the power of which proper relation with the gods and the cosmos

is established. The Veda comprises the liturgy and interpretation of the sacrifice and culminates in the

Upanishads, mystical and speculative works that state the doctrine of Brahman, the absolute reality that is

the self of all things, and its identity with the individual soul, or atman (see Vedanta). Later Upanishads

8

refer to the practices of yoga and contain theistic elements that are fully developed in the Bhagavad-Gita.

Post-Vedic Hinduism in all its forms accepts the doctrine of karma, according to which the individual

reaps the results of his good and bad actions through a series of lifetimes (see transmigration of souls).

Also universally accepted is the goal of moksha or mukti, liberation from suffering and from the

compulsion to rebirth, which is attainable through elimination of passions and through knowledge of

reality and finally union with God.

Responses to Buddhism and Jainism

In the middle of the first millennium B.C., an ossified Brahmanism was challenged by heterodox, i.e.,

non-Vedic, systems, notably Buddhism and Jainism. The priestly elite responded by creating a synthesis

that accepted yogic practices and their goals, recognized the gods and image worship of popular

devotional movements, and adopted greater concern for the daily life of the people. There was an increase

in writings, such as the Laws of Manu (see Manu), dealing with dharma, or duty, not only as applied to

the sacrifice but to every aspect of life. Their basic principle is varna-ashrama-dharma, or dharma in

accordance with varna (class or caste) and ashrama (stage of life). The four classes are the Brahmans,

Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (farmers and merchants), and Shudras (laborers). The four stages of life

are brahmacharya or celibate student life (originally for study of the Veda), grihastha or householdership,

vanaprastha or forest hermitage, and sannyasa, complete renunciation of all ties with society and pursuit

of spiritual liberation. (In practical terms these stages were not strictly adhered to. The two main

alternatives have continued to be householdership and the ascetic life.) The entire system was conceived

as ideally ensuring both the proper function of society as an integrated whole and the fulfillment of the

individual's needs through his lifetime. The post-Vedic Puranas deal with these themes. They also

elaborate the myths of the popular gods. They describe the universe as undergoing an eternally repeated

cycle of creation, preservation, and dissolution, represented by the trinity of Brahma the creator, Vishnu

the preserver, and Shiva the destroyer as aspects of the Supreme.

Medieval and Modern Developments

In medieval times the esoteric ritual and yoga of Tantra and sects of fervent devotion (see bhakti) arose

and flourished. The groundswell of devotion produced poet-saints all over India who wrote religious

songs and composed versions of the epics in their vernaculars. This literature plays an essential part in

present-day Hinduism, as do puja, or worship of enshrined deities, and pilgrimage to sacred places. The

most popular deities include Vishnu and his incarnations Rama and Krishna, Shiva, the elephant-headed

god Ganesha, and the Mother-Goddess or Devi, who appears as the terrible Kali or Durga but also as

Sarasvati, the goddess of music and learning, and as Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth. All the gods and

goddesses, each of which has numerous aspects, are regarded as different forms of the one Supreme

Being. Modern Hindu leaders such as Swami Vivekananda, Mohandas Gandhi, and Aurobindo Ghose,

have given voice to a movement away from the traditional ideal of world-renunciation and asceticism and

have asserted the necessity of uniting spiritual life with social concerns.

Bibliography

See C. N. E. Eliot, Hinduism and Buddhism (3 vol., 1921; repr. 1968); A. B. Keith, The Religion and Philosophy of

the Veda and Upanishads (1925, repr. 1971); Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, The Hindu View of Life (1927, repr. 1962);

Louis Renou, Religions of Ancient India (1953, repr. 1968) and Hinduism (1961); R. G. Zaehner, Hinduism

(1962); A. T. Embree, ed., The Hindu Tradition (1966, repr. 1972); T. J. Hopkins, The Hindu Religious Tradition

(1971); P. H. Ashby, Modern Trends in Hinduism (1974); A. L. Basham, The Origins and Development of

Classical Hinduism (1989).

The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition. Copyright ©1993, Columbia University Press. Licensed from Lernout &

Hauspie Speech Products USA, Inc. All rights reserved.

Author not available, Hinduism (hin´dOOizum). , The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition, 01-01-1993.

9

Buddhism

(The 1998 Canadian Encyclopedia ) LESLIE S. KAWAMURA; 09-06-1997

Buddhism is a major world religion encompassing various systems of philosophy and ethics. It was

founded around 500 BC by a prince of the Sakya clan, Siddhartha Gotama, who came to be known as

Gotama the Buddha. Though accounts of the founder's life vary, the Northern (Sanskrit) and Southern

(Pali) traditions agree that Siddhartha was born in Lumbini Garden (present-day Nepal), attained

enlightenment at Bodhgaya (India), began preaching in Benares (Varanasi) and entered nirvana (passed

away) at Kusinara (Kasia, India).

At the age of 29 Siddhartha turned his back on his life as a prince in order to seek enlightenment. After 6

years as an ascetic he became Buddha (Sanskrit bodhi, "enlightened" or "awakened"), and now

recognized the principle of relativity (the interdependence of all phenomena), which implied that nothing

lasts forever (anitya); everything will eventually become dissatisfying (duhkha); nothing has a nature of

its own (anatman); and, when attachment to calculated and established values is extinguished (nirvana),

bliss (santi) is gained. Thus to become a Buddha does not mean that one becomes divine.

A Buddha is one who recognizes that nothing, including his soul, has an eternal essence. Wishing to share

his insight (dharma), Gotama Buddha preached his first sermon on the Middle Path and on the Four

Noble Truths: the unsatisfactoriness of life, the origin of that unsatisfactoriness, its cessation and the path

leading to its cessation. The 5 monks who attended him were the first Buddhist congregation (sangha) in

Gotama Buddha's 45 years of preaching.

After his death a schism arose between those determined to emulate the religious practices that led

Gotama to enlightenment, and others stressing the experience of enlightenment itself. Gradually 2 distinct

traditions appeared. The Theravada system, developed by those holding the former view, bases its

philosophy and ethics on the Pali texts compiled by Buddhists in southern India. It spread through Burma,

Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Thailand and other South East Asian countries.

The latter system, the Mahayana tradition, bases its philosophy and ethics on the Sanskrit texts from

northern India. It spread to Korea, Vietnam, Japan and other East Asian countries by way of China and

Tibet. As each tradition spread, it changed to accommodate the language, culture, customs and attitudes

of the new country. As well, some Buddhist teachings have influenced, or become integral to, various

NEW RELIGIOUS MOVEMENTS.

LESLIE S. KAWAMURA, Buddhism. , The 1998 Canadian Encyclopedia, 09-06-1997.

******************************************

Buddhism (bood´izum)

(The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition ) ; 01-01-1993

Buddhism (bood´izum)

religion and philosophy founded in India c.525 B.C. by Siddhartha Gautama, called the Buddha. In 1990

there were some 303 million Buddhists worldwide. One of the great world religions, it is divided into two

main schools: the Theravada or Hinayana in Sri Lanka and SE Asia, and the Mahayana in China,

Mongolia, Korea, and Japan. A third school, the Vajrayana, has a long tradition in Tibet and Japan.

Buddhism has largely disappeared from its country of origin, India, except for the presence there of many

refugees from the Tibet region of China and a small number of converts from the lower castes of

Hinduism.

10

Basic Beliefs and Practices

The basic doctrines of early Buddhism, which remain common to all Buddhism, include the "four noble

truths": existence is suffering (dukhka); suffering has a cause, namely craving and attachment (trishna);

there is a cessation of suffering, which is nirvana; and there is a path to the cessation of suffering, the

"eightfold path" of right views, right resolve, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right

mindfulness, and right concentration. Buddhism characteristically describes reality in terms of process

and relation rather than entity or substance. Experience is analyzed into five aggregates (skandhas). The

first, form (rupa), refers to material existence; the following four, sensations (vedana), perceptions

(samjna), psychic constructs (samskara), and consciousness (vijnana), refer to psychological processes.

The central Buddhist teaching of non-self (anatman) asserts that in the five aggregates no independently

existent, immutable self, or soul, can be found. All phenomena arise in interrelation and in dependence on

causes and conditions, and thus are subject to inevitable decay and cessation. The casual conditions are

defined in a 12-membered chain called dependent origination (pratityasamutpada) whose links are:

ignorance, predisposition, consciousness, name-form, the senses, contact, craving, grasping, becoming,

birth, old age, and death, whence again ignorance. With this distinctive view of cause and effect,

Buddhism accepts the pan-Indian presupposition of samsara, in which living beings are trapped in a

continual cycle of birth-and-death, with the momentum to rebirth provided by one's previous physical and

mental actions (see karma). The release from this cycle of rebirth and suffering is the total transcendence

called nirvana.

From the beginning, meditation and observance of moral precepts were the foundation of Buddhist

practice. The five basic moral precepts, undertaken by members of monastic orders and the laity, are to

refrain from taking life, stealing, acting unchastely, speaking falsely, and drinking intoxicants. Members

of monastic orders also take five additional precepts: to refrain from eating at improper times, from

viewing secular entertainments, from using garlands, perfumes, and other bodily adornments, from

sleeping in high and wide beds, and from receiving money. Their lives are further regulated by a large

number of rules known as the Pratimoksa. The monastic order (sangha) is venerated as one of the "three

jewels," along with the dharma, or religious teaching, and the Buddha. Lay practices such as the worship

of stupas (burial mounds containing relics) predate Buddhism and gave rise to later ritualistic and

devotional practices.

Early Buddhism

India during the lifetime of the Buddha was in a state of religious and cultural ferment. Sects, teachers,

and wandering ascetics abounded, espousing widely varying philosophical views and religious practices.

Some of these sects derived from the Brahmanical tradition (see Hinduism), while others opposed the

Vedic and Upanishadic ideas of that tradition. Buddhism, which denied both the efficacy of Vedic ritual

and the validity of the caste system, and which spread its teachings using vernacular languages rather than

Brahmanical Sanskrit, was by far the most successful of the heterodox or non-Vedic systems. Buddhist

tradition tells how Siddhartha Gautama, born a prince and raised in luxury, renounced the world at the age

of 29 to search for an ultimate solution to the problem of the suffering innate in the human condition.

After six years of spiritual discipline he achieved the supreme enlightenment and spent the remaining 45

years of his life teaching and establishing a community of monks and nuns, the sangha, to continue his

work.

After the Buddha's death his teachings were orally transmitted until the 1st century B.C., when they were

first committed to writing (see Buddhist literature; Pali). Conflicting opinions about monastic practice as

well as religious and philosophical issues, especially concerning the analyses of experience elaborated as

the systems of Abhidharma, probably caused differing sects to flourish rapidly. Knowledge of early

differences is limited, however, because the earliest extant written version of the scriptures (1st century

A.D.) is the Pali canon of the Theravada school of Sri Lanka. Although the Theravada [doctrine of the

elders] is known to be only one of many early Buddhist schools (traditionally numbered at 18), its beliefs

as described above are generally accepted as representative of the early Buddhist doctrine. The ideal of

11

early Buddhism was the perfected saintly sage, arahant or arhat, who attained liberation by purifying self

of all defilements and desires.

The Rise of Mahayana Buddhism

The positions advocated by Mahayana [great vehicle] Buddhism, which distinguishes itself from the

Theravada and related schools by calling them Hinayana [lesser vehicle], evolved from other of the early

Buddhist schools. The Mahayana emerges as a definable movement in the 1st century B.C., with the

appearance of a new class of literature called the Mahayana sutras. The main philosophical tenet of the

Mahayana is that all things are empty, or devoid of self-nature (see sunyata). Its chief religious ideal is the

bodhisattva, which supplanted the earlier ideal of the arahant, and is distinguished from it by the vow to

postpone entry into nirvana (although meriting it) until all other living beings are similarly enlightened

and saved. The bodhisattva is an actual religious goal for lay and monastic Buddhists, as well as the name

for a class of celestial beings who are worshiped along with the Buddha. The Mahayana developed

doctrines of the eternal and absolute nature of the Buddha, of which the historical Buddha is regarded as

a temporary manifestation. Teachings on the intrinsic purity of consciousness generated ideas of potential

Buddhahood in all living beings. The chief philosophical schools of Indian Mahayana were the

Madhyamika, founded by Nagarjuna (2d century A.D.), and the Yogacara, founded by the brothers

Asanga and Vasubandhu (4th century A.D.). In this later Indian period, authors in different schools wrote

specialized treatises, Buddhist logic was systematized, and the practices of Tantra came into prominence.

The Spread of Buddhism

In the 3d century B.C. the Indian emperor Asoka greatly strengthened Buddhism by his support and sent

Buddhist missionaries as far afield as Syria. In succeeding centuries, however, the Hindu revival initiated

the gradual decline of Buddhism in India. The invasions of the White Huns (6th century) and the Muslims

(11th century) were also significant factors behind the virtual extinction of Buddhism in India by the 13th

century. In the meantime, however, its beliefs had spread widely. Sri Lanka was converted to Buddhism

in the 3d century B.C., and Buddhism has remained its national religion. After taking up residence in Sri

Lanka, the Indian Buddhist scholar Buddhaghosa (5th century A.D.) produced some of Theravada

Buddhism's most important scholastic writings. In the 7th century Buddhism entered Tibet, where it has

flourished, drawing its philosophical influences mainly from the Madhyamika, and its practices from the

Tantra. Buddhism came to SE Asia in the first five centuries A.D. All Buddhist schools were initially

established, but the surviving forms today are mostly Theravada. About the 1st century A.D. Buddhism

entered China along trade routes from central Asia, initiating a four-century period of gradual

assimilation. In the 3d and 4th centuries Buddhist concepts were interpreted by analogy with indigenous

ideas, mainly Taoist, but the work of the great translators Kumarajiva and Hsüan-tsang provided the basis

for better understanding of Buddhist concepts.

The 6th century saw the development of the great philosophical schools, each centering on a certain

scripture and having a lineage of teachers. Two such schools, the T'ien-t'ai and the Hua-yen,

hierarchically arranged the widely varying scriptures and doctrines that had come to China from India,

giving preeminence to their own school and scripture. Branches of Madhyamika and Yogacara were also

founded. The two great nonacademic sects were Ch'an or Zen Buddhism, whose chief practice was sitting

in meditation to achieve "sudden enlightenment," and Pure Land Buddhism, which advocated repetition

of the name of the Buddha Amitabha to attain rebirth in his paradise. Chinese Buddhism encountered

resistance from Confucianism and Taoism, and opposition from the government, which was threatened by

the growing power of the tax-exempt sangha. The great persecution by the emperor Wu-tsung (845) dealt

Chinese Buddhism a blow from which it never fully recovered. The only schools that retained vitality

were Zen and Pure Land, which increasingly fused with one another and with the native traditions, and

after the decline of Buddhism in India, neo-Confucianism rose to intellectual and cultural dominance.

From China and Korea, Buddhism came to Japan. Schools of philosophy and monastic discipline were

transmitted first (6th century-8th century), but during the Heian period (794-1185) a conservative form of

Tantric Buddhism became widely popular among the nobility. Zen and Pure Land grew to become

12

popular movements after the 13th century. After World War II new sects arose in Japan, such as the Soka

Gakkai, an outgrowth of the nationalistic sect founded by Nichiren (1222-82), and the Risshokoseikai,

attracting many followers.

Bibliography

See H. C. Warren, Buddhism in Translations (1896, repr. 1963); D. T. Suzuki, Zen Buddhism (1956); Arthur

Wright, Buddhism in Chinese History (1959, repr. 1979); Edward Conze, Buddhism (1953, repr. 1959), Buddhist

Scriptures (1959), and Buddhist Thought in India (1962, repr. 1967); Erik Zürcher, Buddhism (1962); K. S. S.

Ch'en, Buddhism in China (1964, repr. 1972); W. T. de Bary, The Buddhist Tradition in India, China, and Japan

(1969); Trevor Ling, The Buddha (1973); Robert Lester, Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia (1973); Walpola

Rahula, What the Buddha Taught (2d ed. 1974); Daigan and Alicia Matsunaga, Foundations of Japanese Buddhism

(1974-76); S. J. Tambiah, World Conqueror and World Renouncer (1976); Leon Hurvitz, Scripture of the Lotus

Blossom of the Fine Dharma (1976); R. H. Robinson, The Buddhist Religion (3d ed. 1982); and Richard Gombrich,

Theravada Buddhism (1988); Jun Ishikawa, The Bodhisattva (1990).

The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition. Copyright ©1993, Columbia University Press. Licensed from Lernout &

Hauspie Speech Products USA, Inc. All rights reserved.

Author not available, Buddhism (bood´izum). , The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition, 01-01-1993.

13