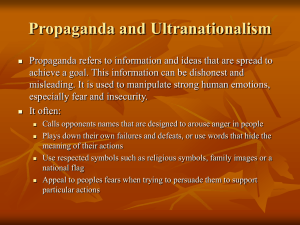

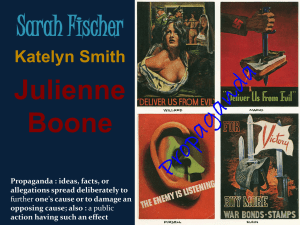

Nazi Propaganda and the Volksgemeinschaft

advertisement