The Power of the Slanted Word

advertisement

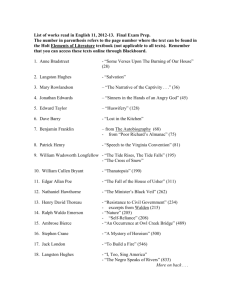

NYISSIA SPRUILL NYISSIA SPRUILL The Power of the Slanted Word Every poet has a style. Sometimes, that style changes from literary piece to literary piece, but nevertheless something shines through the poem to tell the reader it is specifically this poet and no other. Langston Hughes has a trend in some of his poems. He uses italics in order to convey something surprising or something that could not be spoken out loud. He uses this technique in three poems—“Genius Child” (1937), “Harlem” (1951), and “World War II” (1949). The italics seem to serve as whispers or echoes. Perhaps his use of italics reflects back to his generation during the Harlem Renaissance where, artistically, there was a boom among African-Americans, but socially and politically there was an ongoing repression and struggle to be recognized and respected by white people. These italics may reflect those times when how one truly felt could not be said. It had to be whispered. During the 1930s, even talent had to be a secret. In “Genius Child,” Langston Hughes writes of a child considered dangerous because of his intelligence. It is possible that he is writing of himself, as he was and is considered a genius. The line “Nobody loves a genius child” (“Genius Child,” ll. 5, 11) appears, italicized, in the middle and at the end of the poem. This placement clarifies and emphasizes the lines in the first stanza that say, “Sing it softly, for the song is wild. / Sing it softly as ever you can— / Lest the song get out of hand” (ll. 2–4). The italicized line is placed after these lines, suggesting that “Nobody loves a genius child” (l. 5) is the song that is supposed to be sung so softly. But why must such a thing be sung softly? Is it perhaps because to be a genius child is wrong? No, there is nothing wrong with being a genius child. But to be so as an African-American in the 1930s was wrong. It was wrong socially and politically. At that time, intelligence or talent from the African-American community was not something praised outside of it; nobody loved a genius child from the African-American community. To whites, he was a threat to their theory of why they segregated themselves. To African-Americans, he was a hero but at the same time his existence clashed with the ideas of some AfricanAmericans who believed themselves to be inferior. Throughout the poem, Hughes clarifies these ideas, and in doing so, helps accentuate 1 DISCOVERIES and explain his use of italics. Langston Hughes uses the rest of the poem to help the reader attain a better understanding of this genius child. Ingeniously, after he states that it is not possible for one to love a genius child, he places himself in the shoes of his oppressors. Can you love an eagle, Tame or wild?” Wild or tame, Can you love a monster Of frightening name? (“Genius Child,” ll. 6–10) He is the eagle, the monster, and he understands how one could not love things wild or tame. For how can one love another who presents danger, or causes fear? This is the underlying question that causes Hughes to end the above lines in question marks. As a genius child, he caused fear, because he was an obvious negation of one of the reasons why African-Americans were oppressed. African-Americans were considered to lack the intellectual capacity to perform complicated, sophisticated tasks; thus they were kept as porters and maids. But Langston was different, and this was a threat. Thus after the repetition of the italicized line, Langston italicizes another line at the end—“Kill him” (l. 12). Just as “uppity” African-Americans were lynched in the South, unwanted intellectuals were “lynched” in the North also. However, in the North they were not killed literally, but little by little their spirit was killed until they willingly lost that thing that made them special. “Nobody loves a genius child” (ll. 5, 11) for he is a threat to a justified, separatist way of life. Then what should one do with him? Langston Hughes is well aware of the answer. A genius child cannot even whisper, it must be hushed permanently or killed, so that only his harmless “soul [can] run wild” (l. 12). So one must “sing [the song] softly” (ll. 2–3) or else one will not be tolerated. Thus, Hughes uses italics. But how long can one allow oneself to be held down from singing out loud? In “Harlem” Langston Hughes wonders what happens to a dream that is constantly quieted and promised but never fulfilled. In the historical background, the reader should recognize that the “deferred dream” (“Harlem,” l. 1) refers to the Civil Rights Movement and the promises made by the government to better the social conditions of African-Americans. 2 NYISSIA SPRUILL However, these promises were left unfulfilled. What will happen to this “dream deferred” (l. 1)? Eventually, it no longer will be deferred. It will become a reality through force rather than by waiting for the actions of others. This force will not necessarily be violent. There were peacefully resistant demonstrations during the Civil Rights Movement. Nonetheless, the demonstrations reflected a people who were tired of promises and ready for a change. The initial idea for such an explosion cannot be blatant. In the beginning it can only be suggested and whispered, because if the beginnings of resistance are discovered, it will be destroyed. Thus, Langston uses italics in the last verse of the poem. The line “Or does it explode” (l. 11) refers to the dream finally coming to fruition through exciting and controversial means. Such a desire to change society has to be whispered at first. Hughes realizes other possible results of a dream deferred. Using question marks, He explores the numerous possible reactions to a dream constantly repressed by others. These other possibilities lead up to the italicized part, and in doing so emphasize the strength of his question of whether the deferred dream will explode. Through similes and imagery he emphasizes these possible reactions: Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore— And then run? (“Harlem,” ll. 2–5) Here two possibilities are presented. One could just forget the dream, give up and believe that it will never happen. Or one could let desire for the repressed dream escalate and out of frustration react violently to those who repressed it. The direct distinction in “dry up” and “fester . . . then run” is what aids in describing possibilities that are distinctively different from each other. The contrast of similes helps each idea accentuate the other. In the same stanza, Langston presents two more possibilities: Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar over— Like a syrupy sweet? (ll. 6–8) Once again there is a contrast, this time between stinking “rotten meat” and sugary sweets. Is one constantly reminded of this dream, a dream that can never be fulfilled, or is it just forgotten? Interpretation of these 3 DISCOVERIES lines varies from person from person, but there is no denying Langston’s use of sharply contrasting ideas in order to emphasize his points. At the end of the poem, Langston presents another distinction, the most controversial of all. Through it he provides an imploding-exploding image. “Maybe it just sags / like a heavy load.” Maybe the dream remains with the person unfulfilled, but constantly there. “Or does it explode?” (l. 11) This line has the most meaning in the poem, and is its true purpose. The previous contrasts merely lead up to this final distinction. The line is italicized because it is the most controversial of the poem, and the truest meaning is conveyed when, visually, it is distinct from the previous lines. Furthermore, the line can only be italicized—whispered—because such an idea at that time could lead to harm to the person suggesting it. The previously discussed poems identify with Hughes and his contribution to the quest for equality. In “World War II,” however, he does not deal with repression or race, but rather with the effects of war. The poem is different from the others, not only because it is in third person rather than first person, but also because of the way Langston uses italics. Here he uses them to relay a reality that many seemed to have forgotten rather than to communicate social inequality, as in the previous poems. At the beginning of the poem, Langston reflects on the optimism during the time after World War II. Economically, the United States was on a record high, and it is for this reason that Americans were happy. During this part of the poem there seems to be a group voice, as if a conversation is occurring amongst a group of people. One says, “What a grand time was the war” (“World War II,” l. 10), and has an agreeing response of “Oh, my, my” (l. 2). Langston repeats these lines, and his repetition, if not the entire first stanza of the poem, is a representation of American sentiment at the time. It generalizes and makes a collage of the conversations many Americans had regarding the war. Some hoped the war would not end, but there was one of a different sort who realized that the war was not a “grand time” (ll. 1, 3, and 7). It was a time of death and tragedy. This person is recognized in the echo. The echo is italicized, and, as an echo, is most likely meant to be heard as a whisper throughout the entire poem. Furthermore, the italics mark the difference between this new voice and that of the group. “Did / Somebody / Die?” (ll. 10–12) The distinct placement of each word on separate lines adds to the incredulity of the statement, and emphasizes the absurdity that such devastating death could be 4 NYISSIA SPRUILL forgotten. Not only in appearance but also in meaning, the statement serves as a foil to the rest of the poem as an underlying memory that many have chosen to forget, but is there nevertheless. Thus, Langston Hughes uses italics in order to emphasize the taboo subjects of the times. The placement of the italics serves to shock and remind people of what they seem either to not want to know or to have forgotten. The ideas italicized are so controversial they must be whispered for fear that they will be lost or destroyed. For though the italicized words are whispers, like whispers, when spoken softly they are still noticed by others. Thus, these whispers do not serve as quiet sayings that others should not know, but rather as screaming truths that others do not seem to want to know or realize. Historically, we know that Langston was addressing controversial and loud topics of the time. So why not whisper them? ❖❖❖ 5