View/Open - Creighton University

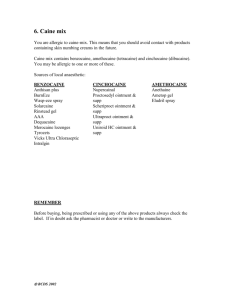

advertisement