Document 1A: Frederick Jackson Turner's Frontier Thesis of

Document 1A : Frederick Jackson Turner's Frontier Thesis of American History

From http://www.blackhills-info.com/quinn/Frontier.html

President Roosevelt's 1905 inauguration lavishly depicted western life. Cowboys prancing

Pennsylvania Avenue, General Custer's old Seventh Cavalry passing for review, and

American Indians, including once-notorious Geronimo, paying their respects to a new

"Great White Father," were all present. The still-fresh frontier experience had many onlookers nostalgic.

Nevertheless, in 1890 the U.S. Census Bureau had proclaimed the frontier closed.

Frederick Jackson Turner, a University of Wisconsin historian, saw great significance in this and in 1893 propounded his now-famous "frontier thesis" before the American Historical

Association. Turner is considered to be the founder of Western history.

The thesis ran:

Up to our own day American history has been in a large degree the history of the colonization of the Great West. The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward explain American development.

The frontier Americanized Americans. The individual was rapidly acclimatized, though the process lasted 300 years. Cheap or even free land provided a "safety valve" which protected the nation against uprisings of the poverty-striken and malcontent. The frontier also transformed the adventurer. The frontier produced a man of coarseness and strength...acuteness and inquisitiveness, [of] that practical and inventive turn of mind...[full of] restless and nervous energy...that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom....

Here was something new, something independent of European experience, Turner thought. The hinterland slighted Eastern habits of deference to authority and its premium on social organization; while social conditions crystallized back East, the West produced the world's first authentically free man. Turner was idealistic about the West. In his

"Contributions of the West to American democracy," he said

The paths of the pioneers have widened into broad highways. The forest clearing has expanded into affluent commonwealths. Let us see to it that the ideals of the pioneer in his log cabin shall enlarge into the spiritual life of a democracy where civic power shall dominate and utilize individual achievement for the common good.

Document 1B : Background on the Morrill Act

Once the South left the Union, the remaining northern states began passing a number of measures which the South had blocked prior to 1860. Many of these laws, such as the authorization of the transcontinental railroads, helped to spur on economic growth and expansion in the western territories.

In 1862 Congress passed two such measures. The Homestead Act permitted any citizen, or any person who intended to become a citizen, to receive 160 acres of public land, and then to purchase it at a nominal fee after living on the land for five years. The

Homestead Act provided the most generous terms of any land act in American history to enable people to settle and own their own farms.

Just as important was the Morrill Act of that year, which made it possible for the new western states to establish colleges for their citizens. Ever since colonial times, basic education had been a central tenet of American democratic thought. By the 1860s, higher education was becoming more accessible, and many politicians and educators wanted to make it possible for all young Americans to receive some sort of advanced education.

Sponsored by Congressman Justin Morrill of Vermont, who had been pressing for it since

1857, the act gave to every state that had remained in the Union a grant of 30,000 acres of public land for every member of its congressional delegation. Since under the

Constitution every state had at least two senators and one representative, even the smallest state received 90,000 acres. The states were to sell this land and use the proceeds to establish colleges in engineering, agriculture and military science. Over seventy "land grant" colleges, as they came to be known, were established under the original Morrill

Act; a second act in 1890 extended the land grant provisions to the sixteen southern states.

The importance of the land grant colleges cannot be exaggerated. Although originally started as agricultural and technical schools, many of them grew, with additional state aid, into large public universities which over the years have educated millions of

American citizens who otherwise might not have been able to afford college.

THE MORRILL ACT (1862)

An Act donating Public Lands to the several States and Territories which may provide

Colleges for the Benefit of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That there be granted to the several States, for the purposes

hereinafter mentioned, an amount of public land, to be apportioned to each State a quantity equal to thirty thousand acres for each senator and representative in Congress to which the States are respectively entitled by the apportionment under the census of eighteen hundred and sixty: Provided, That no mineral lands shall be selected or purchased under the provisions of this act.

Sec. 2. And be it further enacted, That the land aforesaid, after being surveyed, shall be apportioned to the several States in sections or subdivisions of sections, not less than one quarter of a section; and whenever there are public lands in a State subject to sale at private entry at one dollar and twenty five cents per acre, the quantity to which said State shall be entitled shall be selected from such lands within the limits of such State, and the

Secretary of the Interior is hereby directed to issue to each of the States in which there is not the quantity of public lands subject to sale at private entry at one dollar and twenty-five cents per acre, to which said State may be entitled under the provisions of this act, land scrip to the amount in acres for the deficiency of its distributive share: said scrip to be sold by said States and the proceeds thereof applied to the uses and purposes prescribed in this act, and for no other use or purpose whatsoever...

Sec. 4. And be it further enacted, That all moneys derived from the sale of the lands aforesaid by the States to which the lands are apportioned, and from the sale of land scrip hereinbefore provided for, shall be invested in stocks of the United States, or of the States, or some other safe stocks, yielding not less than five per centum upon the par value of the said stocks; and that the moneys so invested shall constitute a perpetual fund, the capital of which shall remain forever undiminished, (except so far as may be provided in section fifth of this act,) and the interest of which shall be inviolably appropriated, by each State which may take and claim the benefits of this act, to the endowment, support, and maintenance of at least one college where the leading object shall be, without excluding other scientific and classical studies, and including military tactics, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and mechanic arts, in such manner as the legislatures of the State may respectively prescribe, in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life...

Sixth. No State while in a condition of rebellion or insurrection against the government of the United States shall be entitled to the benefit of this Act...

Source: U.S. Statutes at Large 12 (1862): 503.

Document 1C: Carey Act of 1894

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Carey Act of 1894 allowed private companies in the U.S. to erect irrigation systems in the western, semi-arid states, and profit from the sales of water. Through advertising, these companies attracted farmers to the many states which successfully utilized the act, Notably

Idaho and Wyoming.

The Act established the General Land Office, which was controlled by the federal government. This land office assigned as many as one million acres (4,000 km_) of land for each western state. Each state then had to regulate the new land, selecting private contractors, selecting settlers, and the maximum price they could charge for water.

Potential settlers who met specific requirements were granted 160 acres each. Projects were financed by the development companies, who eventually handed over control to an operating company.

In most states, settlers had to pay an entry fee, plus a small amount for each acre of land, and meet several guidelines. In Iowa, for example, settlers had to cultivate and irrigate at least one sixteenth of their parcel within one year from the date which water became available. After another year, one eighth had to be cultivated, and by the third year — had the settler lived in the land, and paid all necessary fees — they would receive the deed to that parcel.

Document 1D: Timber Culture Act of 1873

Summary:

An 1870s weather hypothesis suggested that growing timber increased humidity and perhaps rainfall. Plains country residents urged the Federal Government to encourage tree planting in that area, believing trees would improve the climate. Also, 1870 government land regulations dictated that home seekers in Kansas, Nebraska, and Dakota could acquire only 320 acres of land. To encourage tree planting and increase the acreage open to entry,

Congress passed the Timber Culture Act in 1873, declaring that 160 acres of additional land could be entered by settlers who would devote forty acres to trees. Some 10 million acres were donated under this act, but fraud prevented substantive tree growth. The act was repealed in 1891.

Document 1E: Desert Land Act of 1877

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Desert Land Act was passed by the United States Congress on 3 March 1877 to encourage and promote the economic development of the arid and semiarid public lands of the Western United States. Through the Act, individuals may apply for a desert-land entry to reclaim, irrigate, and cultivate arid and semiarid public lands.

The act offered 640 acres of land to anyone who would pay a $1.25 an acre and promise to irrigate the land within 3 years. Individuals taking advantage of the act were required to submit proof of their efforts to irrigate the land within three years, but as water was relatively scarce, a great number of fraudulent "proofs" of irrigation (estimated as high as

95% for early claims) were provided.

Document 1F: The Dawes Act--February 8, 1887

Congressman Henry Dawes, author of the act, once expressed his faith in the civilizing power of private property with the claim that to be civilized was to "wear civilized clothes...cultivate the ground, live in houses, ride in Studebaker wagons, send children to school, drink whiskey [and] own property."]

An act to provide for the allotment of lands in severalty to Indians on the various reservations, and to extend the protection of the laws of the United States and the

Territories over the Indians, and for other purposes.

Be it enacted, That in all cases where any tribe or band of Indians has been, or shall hereafter be, located upon any reservation created for their use, either by treaty stipulation or by virtue of an act of Congress or executive order setting apart the same for their use, the President of the United States be, and he hereby is, authorized, whenever in his opinion any reservation or any part thereof of such Indians is advantageous for agricultural and grazing purposes to cause said reservation, or any part thereof, to be surveyed, or resurveyed if necessary, and to allot the lands in said reservations in severalty to any Indian located thereon in quantities as follows:

To each head of a family, one-quarter of a section;

To each single person over eighteen years of age, one-eighth of a section;

To each orphan child under eighteen years of age, one-eighth of a section; and,

To each other single person under eighteen years now living, or who may be born prior to the date of the order of the President directing an allotment of the lands embraced in any reservation, one-sixteenth of a section; . . .

...

SEC. 5. That upon the approval of the allotments provided for in this act by the Secretary of the Interior, he shall . . . declare that the United States does and will hold the land thus allotted, for the period of twenty-five years, in trust for the sole use and benefit of the

Indian to whom such allotment shall have been made, . . . and that at the expiration of said period the United States will convey the same by patent to said Indian, or his heirs as aforesaid, in fee, discharged of such trust and free of all charge or encumbrance whatsoever: . . .

SEC. 6. That upon the completion of said allotments and the patenting of the lands to said allottees, each and every member of the respective bands or tribes of Indians to whom allotments have been made shall have the benefit of and be subject to the laws, both civil and criminal, of the State or Territory in which they may reside; . . .And every Indian born within the territorial limits of the United States to whom allotments shall have been made under the provisions of this act, or under any law or treaty, and every Indian born within the territorial limits of the United States who has voluntarily taken up, within said limits, his residence separate and apart from any tribe of Indians therein, and has adopted the habits of civilized life, is hereby declared to be a citizen of the United States, and is entitled to all the rights, privileges, and immunities of such citizens, whether said Indian has been or not, by birth or otherwise, a member of any tribe of Indians within the territorial limits of the United States without in any manner impairing or otherwise affecting the right of any such Indian to tribal or other property. . . .

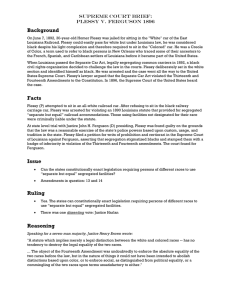

Document 1G : Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark United States Supreme Court decision in the jurisprudence of the United States, upholding the constitutionality of racial segregation even in public accommodations (particularly railroads), under the doctrine of

"separate but equal".

The decision was handed down by a vote of 7 to 1, with the majority opinion written by

Justice Henry Billings Brown and the dissent written by Justice John Marshall Harlan.

"Separate but equal" remained standard doctrine in U.S. law until its final repudiation in the later Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

Background

After the end of the American Civil War in 1865, during the period known as

Reconstruction, the federal government was able to provide some protection for the civil rights of the newly-freed slaves. But when Reconstruction abruptly ended in 1877 and federal troops were withdrawn, southern state governments began passing Jim Crow laws that prohibited blacks from using the same public accommodations as whites. The

Supreme Court had ruled, in the Civil Rights Cases (1883), that the Fourteenth

Amendment applied only to the actions of government, not to those of private individuals, and consequently did not protect persons against individuals or private entities who violated their civil rights. In particular, the Court invalidated most of the Civil Rights Act of

1875, a law passed by the United States Congress to protect blacks from private acts of discrimination.

In 1890, the State of Louisiana passed Act 111 that required separate accommodations for blacks and whites on railroads, including separate railway cars, though it specified that the accommodations must be kept "equal". Concerned, several black and white citizens in

New Orleans formed an association, the Citizen's Committee to Test the Separate Car Act, dedicated to the repeal of that law. They raised $1412.70 which they offered to the thenfamous author and Radical Republican jurist, Albion W. Tourgee, to serve as lead counsel for their test case. Tourgee agreed to do it pro bono. Later, they enlisted Homer Plessy, who was one-eighth black (an octoroon in the now-antiquated parlance), to serve as plaintiff. Their choice of a plaintiff who could "pass" for white was a deliberate attempt to exploit the lack of clear racial definition in either science or law so as to argue that segregation by race was an "unreasonable" use of state power.

The case

On June 7, 1892, Plessy boarded a car of the East Louisiana Railroad that was designated by whites for use by white patrons only. Although Plessy was only one-eighth black and seveneighths white, under Louisiana state law he was classified as an African-American, and thus required to sit in the "colored" car. When he refused to leave the white car and move to the colored car, he was arrested and jailed. At his trial, Homer Adolph Plessy v. The State of

Louisiana, Plessy argued that the ELR had denied him his constitutional rights under the

Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments. However, the judge presiding over his case,

John Howard Ferguson of Massachusetts, ruled that Louisiana had the right to regulate railroad companies as long as they operated within state boundaries. Plessy was thus found guilty of violating the segregation law, and sentenced to pay a US$300 fine.

Dissatisfied with the outcome of his case, Plessy took it to the Supreme Court of Louisiana.

However, he again found an unreceptive ear; was found guilty once more, and the state

Supreme Court upheld Ferguson's ruling. Undaunted, Plessy took his case all the way to the United States Supreme Court in 1896. Two legal briefs were submitted on Plessy's behalf. One was signed by Albion W. Tourgee and James C. Walker and the other by

Samuel F. Phillips and his legal partners F.D. McKenney and Amoooo Fatlock. Oral arguments were held before the Supreme Court on April 13, 1896. Only Tourgee and

Phillips appeared in the courtroom to speak for the plaintiff (Plessy himself was not present). It would become one of the most famous decisions in American history.

The decision

In a 7 to 1 decision in which Mr. Justice Brewer did not participate,[1] the Court rejected

Plessy's arguments based on the Thirteenth Amendment, seeing no way in which the

Louisiana statute violated it. In addition, the majority of the Court rejected the view that the Louisiana law implied any inferiority of blacks, in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Instead, it contended that the law separated the two races as a matter of public policy.

Justice Brown finally declared, "We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff's argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it."

While the Court did not find a difference in quality between the whites-only and blacksonly railway cars, this was manifestly untrue in the case of most other separate facilities, such as public toilets and cafés, where the facilities designated for blacks were poorer than those designated for whites.

Justice John Marshall Harlan, a former slave owner who experienced a conversion as a result of Ku Klux Klan excesses, and champion of black civil rights, wrote a scathing dissent in which he predicted the court's decision would become as infamous as that in Dred Scott v. Sandford. Harlan went on to say:

But in view of the Constitution, in the eye of the law, there is in this country no superior, dominant, ruling class of citizens. There is no caste here. Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.

It should be noted, however, that Justice Harlan also stated that:

There is a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States. Persons belonging to it are, with few exceptions, absolutely excluded from our country. I allude to the Chinese race.

As an aftermath, the case helped cement the legal foundation for the doctrine of separate but equal, the idea that segregation based on classifications was legal as long as facilities were of equal quality. However, Southern state governments refused to provide blacks with genuinely equal facilities and resources in the years after the Plessy decision. The states not only separated races but, in actuality, ensured differences in quality. In January

1896, Homer Plessy pleaded guilty to the violation and paid the fine.

Influence of Plessy v. Ferguson

Plessy legitimized the move towards segregation practices begun earlier in the South.

Along with Booker T. Washington's Atlanta Compromise address, delivered the same year, which accepted black social isolation from white society, Plessy provided an impetus for further segregation laws. In the ensuing decades, segregation statutes proliferated, reaching even to the federal government in Washington, D.C., which re-segregated during

Woodrow Wilson's administration in the 1910s.

Document 1H: Ida B. Wells, “Lynch Law In All Its Phases,” (1893) from: http://www.blackpast.org/?q=1893-ida-b-wells-lynch-law-all-its-phases

Ida B. Wells emerged in the 1890s as the leading voice against the lynching of African

Americans following the violent lynching of three of her friends . The speech she gave on the subject at Boston's Tremont Temple on February 13, 1893 and which was originally published in Our Day magazine in May 1893, appears below.

I am before the American people to day through no inclination of my own, but because of a deep seated conviction that the country at large does not know the extent to which lynch law prevails in parts of the Republic nor the conditions which force into exile those who speak the truth. I cannot believe that the apathy and indifference which so largely obtains regarding mob rule is other than the result of ignorance of the true situation. And yet, the observing and thoughtful must know that in one section, at least, of our common country, a government of the people, by the people, and for the people, means a government by the mob; where the land of the free and home of the brave means a land of lawlessness, murder and outrage; and where liberty of speech means the license of might to destroy the business and drive from home those who exercise this privilege contrary to the will of the mob. Repeated attacks on the life, liberty and happiness of any citizen or class of

citizens are attacks on distinctive American institutions; such attacks imperiling as they do the foundation of government, law and order, merit the thoughtful consideration of far sighted Americans; not from a standpoint of sentiment, not even so much from a standpoint of justice to a weak race, as from a desire to preserve our institutions. The race problem or negro question, as it has been called, has been omnipresent and all pervading since long before the Afro American was raised from the degradation of the slave to the dignity of the citizen. It has never been settled because the right methods have not been employed in the solution. …. The operations of law do not dispose of negroes fast enough, and lynching bees have become the favorite pastime of the South.

…

On the morning of March 9, the bodies of three of our best young men were found in an old field horribly shot to pieces. These young men had owned and operated the "People's

Grocery," situated at what was known as the Curve a suburb made up almost entirely of colored people about a mile from city limits. Thomas Moss, one of the oldest letter carriers in the city, was president of the company, Cal McDowell was manager and Will Stewart was a clerk. There were about ten other stockholders, all colored men. The young men were well known and popular and their business flourished, and that of Barrett, a white grocer who kept store there before the "People's Grocery" was established, went down. One day an officer came to the "People's Grocery" and inquired for a colored man who lived in the neighborhood, and for whom the officer had a warrant. Barrett was with him and when

McDowell said he knew nothing as to the whereabouts of the man for whom they were searching, Barrett, not the officer, then accused McDowell of harboring the man, and

McDowell gave the lie. Barrett drew his pistol and struck McDowell with it; thereupon

McDowell who was a tall, fine looking six footer, took Barrett's pistol from him, knocked him down and gave him a good thrashing, while Will Stewart, the clerk, kept the special officer at bay. Barrett went to town, swore out a warrant for their arrest on a charge of assault and battery. McDowell went before the Criminal Court, immediately gave bond and returned to his store. Barrett then threatened (to use his own words) that he was going to clean out the whole store. Knowing how anxious he was to destroy their business, these young men consulted a lawyer who told them they were justified in defending themselves if attacked, as they were a mile beyond city limits and police protection. They accordingly armed several of their friends not to assail, but to resist the threatened Saturday night attack. When they saw Barrett enter the front door and a half dozen men at the rear door at 11 o'clock that night, they supposed the attack was on and immediately fired into the crowd, wounding three men. These men, dressed in citizen's clothes, turned out to be deputies who claimed to be hunting for another man for whom they had a warrant, and whom any one of them could have arrested without trouble. When these men found they had fired upon officer of the law, they threw away their firearms and submitted to arrest, confident they should establish their innocence of intent to fire upon officers of the law.

The daily papers in flaming headlines roused the evil passions of whites, denounced these poor boys in unmeasured terms, nor permitted a word in their own defense. The

neighborhood of the Curve was searched next day, and about thirty persons were thrown into jail, charged with conspiracy. No communication was to be had with friends any of the three days these men were in jail; bail was refused and Thomas Moss was not allowed to eat the food his wife prepared for him. The judge is reported to have said, "Any one can see them after three days." They were seen after three days, but they were no longer able to respond to the greetings of friends. On Tuesday following the shootings at the grocery, the papers which had made much of the sufferings of the wounded deputies, and promised it would go hard with those who did the shooting, if they died, announced that the officers were all out of danger, and would recover. The friends of the prisoners breathed more easily and relaxed their vigilance. They felt that as the officers would not die, there was no danger that in the heat of passion the prisoners would meet violent death at hands of the mob. Besides, we had such confidence in the law. But the law did not provide capital punishment for shooting which did not kill. So the mob did what the law could not be made to do, as a lesson to the Afro-American that he must not shoot a white man, no matter what the provocation. The same night after the announcement was made in the papers that thee officers would get well, the mob, in obedience to a plan known to every eminent white man in the city, went to the jail between two and three in the morning, dragged out these young men, hatless and shoeless, put them on the yard engine of the railroad which was in waiting just behind the jail, carried them a mile north of the city limits and horribly shot them to death while the locomotive at a given signal let off steam and blew the whistle to deaden the sound of the firing. "It was done by unknown men," said the jury, yet the Appeal Avalanche which goes to press at 3 a.m., had a two column account of the lynching. The papers also told how McDowell got hold of the guns of the mob and as his grasp could not be loosened, his hand was shattered with a pistol ball and all the lower part of his face was torn away. There were four pools of blood found and only three bodies. It was whispered that he, McDowell killed one of the lynchers with his gun, and it is well known that a police man who was seen on the street a few days previous to the lynching, died very suddenly the next day after. "It was done by unknown parties," said the jury, yet the papers told how Tom Moss begged for his life, for the sake of his wife, his little daughter and his unborn infant. …..

The following table shows the number of men lynched from January 1, 1882, to January 1,

1892: In 1882, 52; 1883, 39; 1884, 53; 1885, 77; 1886, 73; 1887, 70; 1888, 72; 1889, 95; 1890,

100; 1891, 169. Of these 728 black men who were murdered, 269 were charged with rape,

253 with murder, 44 with robbery, 37 with incendiarism, 32 with reasons unstated (it was not necessary to have a reason), 27 with race prejudice, 13 with quarreling with white men,

10 with making threats, 7 with rioting, 5 with miscegenation, 4 with burglary. One of the men lynched in 1891 was Will Lewis, who was lynched because "he was drunk and saucy to white folks." A woman who was one of the 73 victims in 1886, was hung in Jackson, Tenn., because the white woman for whom she cooked, died suddenly of poisoning. An examination showed arsenical poisoning. A search in the cook's room found rat poison.

She was thrown into jail, and when the mob had worked itself up to the lynching pitch, she was dragged out, every stitch of clothing torn from her body, and was hung in the public court house square in sight of everybody. That white woman's husband has since died in the insane asylum, a raving maniac, and his ravings have led to the conclusion that he and not the cook, was the poisonier of his wife. A fifteen year old colored girl was lynched last spring, at Rayville, La., on the same charge of poisoning. A woman was also lynched at Hollendale, Miss. last spring, charged with being an accomplice in the murder of her paramour who had abused her. These were only two of the 159 persons lynched in the South from January 1, 1892, to January 1, 1893. Over a dozen black men have been lynched already since this new year set in, not yet two months old. It will thus be seen that neither age, sex nor decency are spared. Although the impression has gone abroad that most of the lynchings take place because of assaults on white women only one third of the number lynched in the past ten years have been charged with that offense, to say nothing of those who were not guilty of the charge. And according to law none of them until proven so. But the unsupported word of any white person for any cause is sufficient to cause a lynching.

Document 1I : Interstate Commerce Act (1887)

From: http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true&doc=49

In 1887 Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act, making the railroads the first industry subject to Federal regulation. Congress passed the law largely in response to public demand that railroad operations be regulated. The act also established a fivemember enforcement board known as the Interstate Commerce Commission. In the years following the Civil War, railroads were privately owned and entirely unregulated. The railroad companies held a natural monopoly in the areas that only they serviced.

Monopolies are generally viewed as harmful because they obstruct the free competition that determines the price and quality of products and services offered to the public. The railroad monopolies had the power to set prices, exclude competitors, and control the market in several geographic areas. Although there was competition among railroads for long-haul routes, there was none for short-haul runs. Railroads discriminated in the prices they charged to passengers and shippers in different localities by providing rebates to large shippers or buyers. These practices were especially harmful to American farmers, who lacked the shipment volume necessary to obtain more favorable rates.

Early political action against these railroad monopolies came in the 1870s from “Granger” controlled state legislatures in the West and South. The Granger Movement had started in the 1860s providing various benefits to isolated rural communities. State controls of railroad monopolies were upheld by the Supreme Court in Munn v. Illinois (1877). State

regulations and commissions, however, proved to be ineffective, incompetent, and even corrupt. In the 1886 Wabash case, the Supreme Court struck down an Illinois law outlawing long-and-short haul discrimination. Nevertheless, an important result of Wabash was that the Court clearly established the exclusive power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce. (See Gibbons v. Ogden.)

The Interstate Commerce Act addressed the problem of railroad monopolies by setting guidelines for how the railroads could do business. The act became law with the support of both major political parties and pressure groups from all regions of the country.

Applying only to railroads, the law required "just and reasonable" rate changes; prohibited special rates or rebates for individual shippers; prohibited "preference" in rates for any particular localities, shippers, or products; forbade long-haul/short-haul discrimination; prohibited pooling of traffic or markets; and most important, established a five-member

Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC).

The law’s terms often contradicted one another. Some provisions were designed to stimulate competition and others to penalize it. In practice, the law was not very effective.

The most successful provisions of the law were the requirement that railroads submit annual reports to the ICC and the ban on special rates the railroads would arrange among themselves, although determining which rates were discriminatory was technically and politically difficult. Years later the ICC would become the model for many other regulatory agencies, but in 1887 it was unique. The Interstate Commerce Act challenged the philosophy of laissez-faire economics by clearly providing the right of Congress to regulate private corporations engaged in interstate commerce. The act, with its provision for the

ICC, remains one of America’s most important documents serving as a model for future government regulation of private business.