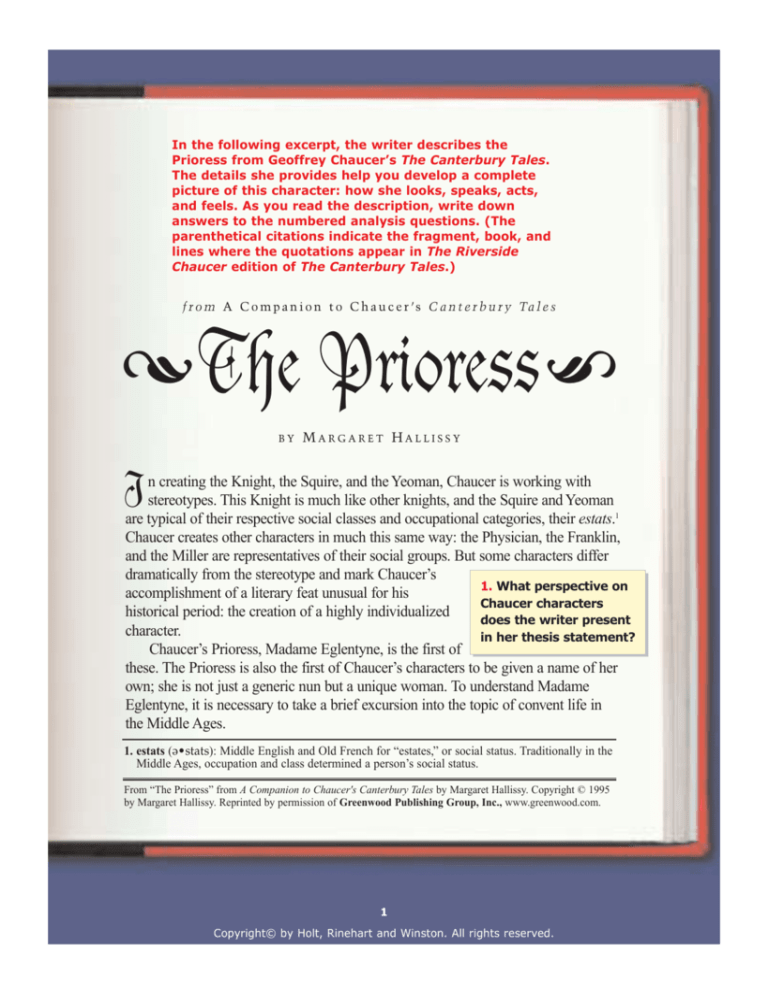

In the following excerpt, the writer describes the

Prioress from Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales.

The details she provides help you develop a complete

picture of this character: how she looks, speaks, acts,

and feels. As you read the description, write down

answers to the numbered analysis questions. (The

parenthetical citations indicate the fragment, book, and

lines where the quotations appear in The Riverside

Chaucer edition of The Canterbury Tales.)

f r o m A C o m p a n i o n t o C h a u c e r ’ s C a n t e r b u r y Ta l e s

The Prioress BY

MARGARET HALLISSY

I

n creating the Knight, the Squire, and the Yeoman, Chaucer is working with

stereotypes. This Knight is much like other knights, and the Squire and Yeoman

are typical of their respective social classes and occupational categories, their estats.1

Chaucer creates other characters in much this same way: the Physician, the Franklin,

and the Miller are representatives of their social groups. But some characters differ

dramatically from the stereotype and mark Chaucer’s

1. What perspective on

accomplishment of a literary feat unusual for his

Chaucer characters

historical period: the creation of a highly individualized

does the writer present

character.

in her thesis statement?

Chaucer’s Prioress, Madame Eglentyne, is the first of

these. The Prioress is also the first of Chaucer’s characters to be given a name of her

own; she is not just a generic nun but a unique woman. To understand Madame

Eglentyne, it is necessary to take a brief excursion into the topic of convent life in

the Middle Ages.

1. estats (ß•stats): Middle English and Old French for “estates,” or social status. Traditionally in the

Middle Ages, occupation and class determined a person’s social status.

From “The Prioress” from A Companion to Chaucer's Canterbury Tales by Margaret Hallissy. Copyright © 1995

by Margaret Hallissy. Reprinted by permission of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc., www.greenwood.com.

1

Copyright© by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved.

Medieval women were perceived as having two basic life choices: religious life

or secular life as married women. Since an unmarried woman had no real place in

medieval society, any woman who could not marry, or who chose not to, affiliated

with a religious order. A woman might become a nun for several reasons. She

might be the real thing: a person with a genuine vocation2 to place her relationship

with God above all else. She might be attracted to the ordered, peaceful life of

prayer, work, and study that the convent offered. Women could pray and work in

any estat; but at a time when intellectual opportunities were available only to the

few, the convent provided a level of education that was not available elsewhere to

women. Less in accord with the intended purpose of convent life was the custom of

using it as an alternative of last resort for women who were for any reason

unmarriageable: those whose families could not afford a dowry (money and/or land

settled upon a girl at marriage); or those who were simply too unattractive to snare

a mate. Since Chaucer’s Prioress is specifically

described as attractive, she may have been consigned 3 to 2. What background

information does the

a convent for reasons of family convenience, because it

writer give about

is clear that she lacks a true religious calling. In Madame

convent life in the

Eglentyne, Chaucer depicts charm without substance.

Middle Ages? How does

Although the Prioress is appealing, she represents the

the Prioress’s physical

decline of convent life in the Middle Ages, from a haven appearance relate to

for saints and scholars to a finishing school for proper,

this information?

but vapid,4 ladies.

The Prioress is exceedingly well-mannered. She smiles sweetly and demurely,

and uses only the mildest oath. She knows how to chant the liturgy, intoning it

through her nose in a seemly manner. She can speak French, a genteel

accomplishment then as now, but only as it is taught in England, not as it is spoken

in Paris; in other words, there is a superficiality even to such limited learning as she

has. Many behavior manuals available in the fourteenth century stressed proper

behavior at table, and the Prioress has learned these social graces. She doesn’t drop

bits of food on the way to her mouth, nor does she allow bits of food to fall onto

her breast; she does not “wet her fingers in the deep [bowls of] sauce” (1, A, 129)

when she dips a bit of food into them, she wipes her upper lip clean of grease

2. vocation (vó•ká’Çßn): a calling.

3. consigned (kßn•sínd’): handed over.

4. vapid (vap’id): dull, shallow, boring.

2

Copyright© by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved.

before she drinks from her wine glass; she reaches for her

3. What details does the

food politely rather than grabbing for it in a rude, lowerwriter provide about the

class manner. All this detail shows that she was “well

Prioress’s manners?

taught” (1, A, 127) on how to behave in company. But

What do these social

what has this to do with the religious life? The fact that

graces suggest about

the Prioress knows such “courtesy” (1, A, 132) suggests

the Prioress’s character?

that she is attracted more to fashionable society than to

the convent.

Other details of Madame Eglentyne’s portrait show that in conducting herself

as a courtly lady she is implicitly violating the spirit of her religious commitment.

“Great deportment,” a pleasant, “amiable,” “stately . . . manner” (1, A, 137–140),

are all qualities more suitable to the courtly lady than to the nun. A nun is not

supposed to “counterfeit the manners/Of court” or worry if she is being “held

worthy of reverence” in society (1, A, 139–141). The cumulative effects of all these

details would indicate to the medieval reader that the Prioress’s values were secular,

not religious; and the point would be reinforced by her behavior with animals.

In the medieval convent, pets were either strongly discouraged or downright

forbidden. Since the nun was supposed to direct her love toward God alone, a pet

would be a distraction, a worldly affection that the nun should reject. But the

Prioress is emotionally overinvolved with animals, particularly small, cute ones:

She was so charitable and so full of pity

That she would weep, if she saw a mouse

Caught in a trap, if it were dead or bled.

(1, A, 143–145)

4. How does this long

quotation support the

writer’s claim that the

Prioress’s feelings

toward animals are

excessive?

This behavior often appeals to animal lovers in Chaucer’s modern audience, but “charity” for the medieval nun is supposed to mean love

directed upward toward God, not directed downward toward what medieval people

regard as lower beings.

Even worse than weeping for a mouse is the Prioress’s 5. What actions of the

Prioress does the writer

behavior with her dogs. Some medieval religious orders

describe in this parallowed cats; but dogs were never allowed. Despite this

agraph? Why are these

prohibition,

actions at odds with her

vocation as a nun?

3

Copyright© by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved.

She had small hounds that she fed

With roasted flesh, or milk and white bread,

And she wept bitterly if one of them were dead.

(1, A, 146–148)

Little lapdogs were popular accessories of the flirtatious courtly lady; she

could cuddle cutely with them, thus displaying her “tender heart” (1, A, 150) and

in general looking utterly adorable. Such behavior would be silly and trivial even

in a marriageable young girl, and it is entirely inappropriate for a nun. The

Prioress’s feeding the small hounds with roast meat and white bread—both

culinary treats in the Middle Ages—shows that her convent is extravagant

(religious rules prescribed humble fare) and that leftovers are not being given to

the poor. The Prioress weeps for dead pets, but she should be weeping for the

sorry state of her own spiritual development. Her “conscience” (1, A, 150) is

misinformed about the proper object of her tender-hearted solicitude.

Her sense of appropriateness is also defective in the matter of her array.5 Nuns

were supposed to be indifferent to their appearance and unconcerned with

clothing. The habits or uniform apparel adopted by religious orders (the wearing

of which was abandoned only in the mid-twentieth century) were based on the

garb of widows. Simple, modest, and inexpensive, the nun’s habit was supposed to

contrast with the lavish array of wealthy women in secular life. Thus the Prioress

violates the spirit of religious life by wearing an attractively pleated wimple or

head-dress, an elegant cloak, and an expensive set of coral prayer beads. Most

questionable of all is her brooch. If lavish and costly clothing was forbidden to a

nun, all the more was jewelry. Worse, this gold brooch

6. What details about

contains an inscription: “Amor vincit omnia,” love

the Prioress’s clothing

conquers all (1, A, 162). What kind of love is suggested

does the writer

by this brooch? The love of God or the love of a man?

provide? Why do you

Chaucer leaves the matter tantalizingly unresolved. But in think she discusses the

presenting a character who conforms to the stereotype of

brooch last?

the courtly lady, with her small nose, her grey eyes, her

small, soft, red mouth, Chaucer calls our attention to the moral ambiguity

surrounding a person whose appearance and behavior fit her more for secular life

than for religious life.

5. array (ß•rá’): fine clothing.

4

Copyright© by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved.