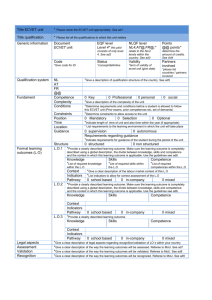

Questions & Answers about ECVET

advertisement