MU 370 Music Literature Proficiency Study Guide

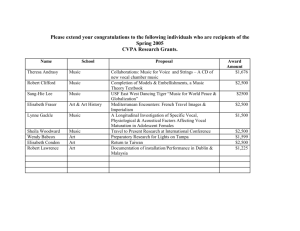

advertisement

Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 1 MU 370 - Music Literature Proficiency Music Core Outcome: Understand how music has been created, performed and perceived throughout history and cultures, while acquiring an acquaintance with a wide selection of music literature. Requirements The student is to describe the stylistic traits of ten musical selections (including descriptions of melody, harmony, texture, emotion, and medium), place the selection in a time-frame and culture, and give reasons for this placement. Listening: 5 selections of music from throughout history and cultures are played. Written: 5 written selections of music (scores) from throughout history and cultures are given. Preparation Courses that help prepare for the proficiency: MU 131 Global Music MU 331/332/333 Music History I, II, III Listening: Attend lots of concerts and recitals, on-campus and off. Take advantage of student discounts. NOTE: Concert attendance is a requirement for MU 284 Music Portfolio. Make sure that the concerts you attend help develop a strong knowledge and experience of the richness of music, including classical. Periodically turn to a classical music radio station (locally KQAC 89.9 – allclassical.org). Try to determine the composer/era/stylistic traits of the piece before the announcer comes back on. Study groups. Get together with peers. Check out recordings from library and play “drop the needle” for each other. One chooses a selection. The others describe the stylistic traits and guess composer/era. One good way to study is to focus upon a certain genre that spans several stylistic eras (for example, a cappella choral music ranging from medieval times to the present, or string quartet that ranges from the classical period to the present). Visual analysis: Make note of the stylistic traits of the music found in the Norton Anthology. Fill out the Stylistic Trait Inventory (page 17) for sample pieces you encounter during your studies. Continually ask: “What makes the music we are studying distinct from previous music I know about? How is it the same?” Review genres, composers, and traits for each period. Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 2 Terminology – Accurate observations of a work’s stylistic traits are clues to a work’s historical place in literature. The concepts embodied in musical terminology help define these traits. A music major should be proficient in the understanding and use of the following technical words: Medium: choir, orchestra, solo keyboard, voice and piano, string quartet, piano quintet, etc. Genre: sacred, secular, choral, vocal, instrumental, symphonic, operatic, chamber music Texture: monophonic heterophonic homophonic (block chords, melody and accompaniment) polyphonic (imitative, non-imitative) Dynamics: none indicated, terraced, abrupt changes, gradual changes, extreme contrast Duration Tempo: none indicated, slow/medium/fast, changes within piece, extremes, detailed instructions Meter: none indicated, duple/triple, simple/compound, ametric/ metric, complex, changing, polymetric Patterns: present/not present Type: rhythmic modes (patterns of long/short), pattern length (beat, measure, phrase) Sub-divisions of beat: 2’s, 3’s, 4’s, 5’s, 7’s etc Syncopations Pitch Scale basis: modal, diatonic, chromatic, pentatonic, 12-tone row, pitch-set, octatonic Chord type(s): perfect intervals triadic, seventh chords, extended tertian, altered, added notes quartal, clusters degree of tension: consonant/dissonant Chord progression/harmonic movement: functional (I-IV-V-I type progressions), root movements by 2nds or 3rds or 5ths, harmonic rhythm (regular/irregular, fast/slow) Cadences: perfect/imperfect authentic, plagal, Landini, step-wise, deceptive, incomplete Tonality: beginning and ending on same/different pitch centers, modulations, atonal, polytonal Melody/phrase: Relationship between notes (conjunct/disjunct) Range (narrow/wide) Complexity (simple/ornamented) Phrases (symmetrical/irregular, antecedent/consequent, length: 2+2+4) Construction (motivic, sequential) Character (vocal/instrumental, lyric, gestural, virtuosic) Text Language (Latin, Italian, French, German, English, etc.) Type (mass: ordinary/proper, poetry, prose) Relationship of text to music: syllabic/melismatic text-painting strophic/through-composed Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 3 WESTERN EUROPEAN MUSIC TRAITS MEDIEVAL (Antiquity to 1400) ELEMENT Antiquity to 1200 Dynamics None indicated Medium Solo or 2-part vocal, unison chorus; instrumental melodies and vocal accompaniment. Ars Antiqua (1200-1300) Ars Nova (1300-1400) Secular: 1, 2, and 3 pt. vocal. Secular: 2, 3-part vocal Sacred: 1, 2, 3, & 4 pt. vocal. Sacred: 2, 3, & 4 pt. vocal. Instrumental dance music: rare indications of specified insts. Insts. used to accompany or replace vocal parts. Duration Tempo derived from meter. Meter & rhythmic patterns related to rhythmic modes/poetic meters. mensural notation; more complex rhythms, some extreme syncopation. Pitch Scales medieval modes derived from Ancient Greek modes Melody No symmetrical phrases; little use of sequence and repetitions; conjunct lines; vocally conceived More disjunct; Secular: repetition according to fixed forms. Chords & tonality No functional tonality No chords, intervals in organum P1, P4, P5, P8 considered consonant, other intervals considered dissonant but widely used in mid-phrase. P intervals, also 3rds, 6ths, some triads Final cadences P5 or P8 sonority Linear approach (7-8,2-1) Texture Monophonic 2, 3, 4-part non-imitative polyphony bottom line has cantus firmus (from chant) and generally moves slower top line usually moves most active Forms All periods: mostly vocal forms used by voices and instruments. hymns, theater music. Chant, organum, secular songs Composers Sacred motet (using cantus firmus, 2,3,4-part voices) Instrumental dances Isorhythmic motet Mass movements Virelai, ballade, rondeau Ballata, caccia, madrigal Anonymous Secular troubadours, trouvères, minnesingers Euripides (fl. 5th century BCE) Leonin (fl. 1175, France) Perotin (fl. 1180-1220, France) Guillaume de Machaut (c. 1300-1377, France) Francesco Landini (c. 1325-1397, Italy) Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 4 RENAISSANCE (1400-1600) Dynamics None indicated until late 16th century Medium Vocal: 2,3,4,5-parts, occasionally more, instruments double voice lines or play alone Instrumental: specific compositions for keyboard, lute, and viol are written. Duration Tempo derived from time signature. Meter Duple and triple (no bar-lines used). Individual lines often work independently Rhythmic patterns Less use of rhythmic patterns than in medieval music. Melodies in motets and mass movements often move from slow to fast durations, without any repetitions of rhythmic patterns. Pitch Scales Medieval or "church" modes; use of accidentals approaches major and minor. Melody Sacred music avoids symmetry. Some use of sequence and repetition. Secular music sometimes has more balanced phrases. Added leading tones, some chromaticism. Chords Perfect intervals; major and minor triads; other sounds treated carefully. Chords arise from combination of melodies. Suspensions common. Chord progression and tonality Functional harmony not present although many V-I and IV-I cadences. Some focus on different tonal centers at beginning and end. Final cadences Perfect intervals, major triads, minor triads extremely rare in practice. Texture Homophony (blocked chords) in secular songs, early madrigal, chanson, and a few sacred works Polyphony (2, 3, 4 or more voices) in sacred works and later madrigals. Imitative polyphony (beginning of each line) in 16th century. Many sacred works based upon cantus firmus. Forms Sacred: motet, mass, complete mass settings often cyclic (based upon cantus firmus) Secular: chanson, madrigal, lied Instrumental: canzona, ricercare, in nomine, dance pairs. Composers John Dunstable (c. 1385-1453, English) Guillaume Dufay (c. 1400-1474, Franco-Flemish) Gilles Binchois (c. 1400-1460, French) Johannes Ockeghem (c. 1430-1497, Netherlands) Josquin des Prez (c. 1440-1521, Franco-Flemish) Heinrich Isaac (c. 1450-1517, Netherlands) Jacob Obrecht (c. 1451-1505, Franco-Flemish) Giovanni da Palestrina (c. 1525-1594, Italy) Roland de Lassus (1532-1594, Franco-Flemish) William Byrd (1543-1623, English) Tómas Luís de Victoria (c. 1949-1611, Spanish) Giovanni Gabrielli (c. 1557-1612, Italian) Carlo Gesualdo (c. 1560-1613, Italian) Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643, Italian) Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 5 BAROQUE (1600-1750) Dynamics Terraced, abrupt loud-soft changes Medium Presence of continuo (a harmonic bass line played by a bass instrument with chordal realization played by keyboard player) Instrumental: Trio sonata (2 treble instruments and continuo), solo keyboard, ensembles Vocal: solo and chorus, opera, oratorio, cantata Duration Tempo Slow, moderate, fast; few changes within piece especially in later Baroque, no real extremes. Meter Duple and triple (both simple and compound). Standard meters for specific dance movements. Meter reinforced by regular harmonic rhythm. Rhythmic patterns Lots of repetition and very metric. Limited number of note values in a piece, especially fast ones. Slow movements have more variety; they are often decorations. Pitch Scales Major and minor; some remnants of the church modes. Melody Some symmetrical phrases (especially in dance movements), but often melodies are through-composed, based upon one rhythmic or pitch pattern without symmetric phrase structure. Sequences are prevalent. Instrumentally-conceived lines (even in vocal music), often disjunct and with wide range. Chords Major and minor triads. Mm7, mm7, dim 7th’s; occasionally other 7th’s. Extensive use of non-chords tones, used very carefully. Harmonic foundation controls melodic lines, rather than melody lines creating harmony as in the Renaissance. Chromaticism: secondary chords and modulations to closely-related keys. Chord progression and tonality Functional harmony (I-IV-V-I) prevalent by 1650. Cycle of 5th’s. Regular harmonic rhythm supports meter. Final cadences Major and minor triads. Authentic and plagal cadences. Use of anticipations and suspensions. Occasional use of pedal point to extend final cadence. Texture Continuo homophony Chorale - homophony (block chords) with some independence in each line Trio sonata (4 players) Concerto grosso (group of soloists with larger ensemble) Polyphonic textures in fugues Some pieces based upon a cantus firmus (these are often chorale tunes rather than chants) Forms Binary forms found in dance movements (suites) Ostinato variations: ground, chaconne, passacaglia Ritornello movements in concerto movements Fugue Larger multi-movement vocal works: cantata, passion, mass, opera, oratorio Vocal forms (single movements within larger works): da capo aria, recitative, chorus Keyboard: preludes, toccatas, fantasias, chorale preludes Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Baroque (continued) Composers Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643, Italian) Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643, Italian) Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672, German) Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687, Italian/French) Dietrich Bxtehude (c. 1637-1707, German) Arcangelo Correlli (1653-1713, Italian) Henry Purcell (c. 1659-1695, English) Alessandro Scarletti (1660-1725, Italian) François Couperin (1668-1733, French) Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741, Italian) Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764, French) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750, German) George Frideric Handel (1685-1759, German) Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757, Italian) Page 6 Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 7 CLASSICAL (1750-c.1820) Dynamics Loud, soft, gradual changes with use of crescendo and diminuendo signs Medium Vocal: opera, mass, oratorio, solo song Instrumental: piano chamber groups (string trio, string quartet, string quintet, piano trio, mixed groups) solo instrument with piano (i.e. piano and violin sonata) orchestra: moderate sized. Emphasis on strings (melody in violins). Winds in pairs with contrasting melodic material. Orchestration is in blocks (by phrase and section). Duration Tempo Slow, moderate, fast. Few changes within piece, although the impression may be that there are contrasts (for example in a sonata, the secondary theme in whole notes may sound slower than the primary theme in eighth and sixteenth notes) Extremes of tempos are beginning to be explored (such as very fast finales) Meter Duple and triple (simple and compound). Set meter in certain dance movements (minuet and trio) Rhythmic patterns Metric patterns with occasional syncopation. Reuse of limited number of patterns, less than baroque. Pitch Scales Major and minor Melody Clear balance of phrase structure (4+4, antecendent/consequent) Motivic development in use, but a balance of unity and contrast in play as well. Sequence often important. Melodies often exhibit balance between disjunct (instrumental) and conjunct (vocal) Outlining triads and seventh chords are important melodic element. Chords Major and minor triads; seventh chords; chromatic chords including diminished seventh chords in from parallel minor, augmented 6th chords, Neapolitans) Chord progression and tonality Functional harmony (I-IV-V-I) strongly evident; regular harmonic rhythm; may slow down at cadences. Modulations to closely-related keys. Final cadences Authentic cadences (V7-I) with major and minor triads. Texture Melody and accompaniment is primary texture, with many different type of accompaniment patterns Polyphonic lines added to this homophonic texture Absence of cantus firmus-based pieces Composers such as Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven experiment with more polyphonic textures Forms Individual movements Sonata-movement (exposition, development, recapitulation) Rondo Theme and Variations Minuet and Trio; Scherzo-Trio Multi-movement works Instrumental: Symphony, Sonata, Concerto, String Quartet Solo voice: art song, German lieder Larger vocal works: mass, oratorio, opera (recitative-aria) Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Classical (continued) Composers Giovanni Sammartini (1701-1775, Italian) Giovanni Battista Pergolesi (1710-1736, Italian) Carl Phillip Emanuel Bach (1714-1788, German) Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787, Bohemia) Johann Stamitz (1717-1757, German) Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809, Austrian) Johann Christian Bach (1735-1782, German) Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805, Italian) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791, Austrian) Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827, German) Page 8 Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 9 ROMANTIC/19TH CENTURY Dynamics Extreme contrasts in dynamic levels and abrupt changes Medium Vocal: voice and piano, solo voice/choir with orchestra (opera, mass, oratorio) Piano Piano and solo instruments Chamber groups (piano trio, string quartet, woodwind quintet) Orchestra: expanded in size. Melodic material in all instruments, use of solo instruments for color. Addition of large woodwind, brass (and perhaps percussion) sections. Duration Tempo Extremes of tempo; many changes within piece; elaborate instructions given including “character” markings. Meter Duple and triple (simple and compound). Some free sections. Rhythmic patterns Metrical and simple in some works. Others use varied rhythmic patterns, syncopation, or other devices to shift the beat or obscure metric structure. Symmetry of phrase still prevalent, especially in dance works. Pitch Scales Major and minor, but also evidence of borrowing between them. Much more use of chromaticism. Melody Less emphasis on balance and clarity; more emphasis on dramatic and expressive elements. Cadences avoided to create longer sections. Motivic development important to some (ie. Brahms). Other composers strive for mood transformation of melody by tempo, dynamic and timbral changes. Chords All triads and sevenths. Later in century use of 9th’s, 11th’s, and 13th’s. Chromatic chords: borrowed chords, secondary dominants, augmented 6th’s, Chord progression and tonality Functional harmony (I-IV-V-I) still prevalent, but expanded by chord substitutions, delay of resolutions, slowing down harmonic rhythm, and modulating or abrupt shifts to distantly-related keys (such as chromatic thirds). Final cadences Major and minor triads (V7-I), but often prolonged/delayed and decorated. Texture Primary texture is melody and accompaniment. Some use of non-imitative polyphony (usually to evoke an older historical period). Forms Continuation of classical models, but seen less as principles of development and more as formal structures. These structures tend to be expanded by length and complexity. Connection between movements (cyclic forms). Extra-musical considerations: program music. Piano: intermezzo, etude, nocturne, rhapsody, fantasy, as well as sonata. Voice: art song, song cycle. Chamber ensembles such as string quartet, piano trio. Orchestral: symphonies, tone-poems Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Romantic (continued) Composers Gioacchino Rossini (1792-1868, Italian) Franz Schubert (1797-1828, Austrian) Gaetano Donizetti (1797-1848, Italian) Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835, Italian) Hector Berlioz (1803-1869, French) Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy (1809-1847, German) Frédéric Chopin (1810-1856, Polish) Robert Schumann (1810-1856, German) Franz Liszt (1811-1886, Hungarian) Giuseppi Verdi (1813-1901, Italian) Richard Wagner (1813-1883, German) Anton Bruckner (1824-1896, Austrian) Johannes Brahms (1833-1897, German) Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893, Russian) Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904, Czech) Edvard Grieg (1843-1907, Norwegian) Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924, Italian) Hugo Wolf (1860-1903, Austrian) Gustav Mahler (1860-1911, Austrian) Claude Debussy (1860-1918, French) Richard Strauss (1864-1940, German) Jean Sibelius (1865-1957, Finnish) Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) Page 10 Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 11 CONTEMPORARY (1900-present) Dynamics Quite varied between composers, extreme emphasis in some; some works have every note marked a different dynamic. Medium All traditional combinations (voice and instruments) in every possible combination. Electronics, recordings of natural sounds, variety of percussion and non-western instruments. Duration Varies from very simple to very complex. New notations using time graphs and performer-controlled determinations. Addition of mixed meters, unusual groupings (2-3-2-2), non-synchronous meters. Pitch Scales Use of variety of pitch systems: major and minor scales; modes; symmetric scales such as octatonic; nonwestern scales; 12-tone rows; microtones. Melody Ranges from very short ideas with limited pitches to extremely disjunct non-symmetrical lines. Some pieces avoid any semblance of melody. Chords All possibilities: tertian, quartal, secundal, symmetric structures, poly-chords, no chordal basis. Chord progression and tonality Some composers continue to use functional tonality; some will avoid it. Some find ways to create tonal centers without the use of functional harmonic progressions. Some will explore bi-tonality. Final cadences Depends upon musical language and aesthetic chosen. Texture Any combination of monophonic, homophonic, or polyphonic. Sound blocks: juxtaposition, stratification, Explorations of new sounds and textures. Forms No predictable model. Use of forms from earlier times as well as new ones. Chance music (aleatory) NOTE: Beginning in the early 20th-century, composers of western music “art-music” have been involved in diverse musical styles. It is difficult to describe a unified style. Popular music has tended to be based upon a more functional/traditional foundation. Composers Charles Ives (1874-1954, American) Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951, Austrian) John Cage (1912-1992 , American) Benjamin Britten (1913-1976, English) Béla Bartók (1881-1945, Hungarian) Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971, Russian) Anton Webern (1883-1945, Austrian) Edgard Varèse (1883-1965, French) Pierre Boulez (b. 1925, French) Luciano Berio (b. 1925-2003 , Italian) Karlheinz Stockhausen (b. 1928, German) George Crumb (b. 1929, American) Paul Hindemith (1895-1963, German) Krzysztof Pendericki (b. 1933, Polish) Aaron Copland (1900-1990, American) Elliott Carter (1908- , American) Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992, French) John Adams (b. 1947, American) list incomplete These charts are based upon those in An Introduction to the Literature and Structure of Music by David Neumeyer and Mary H. Wennerstrom (Waveland Press, 1980) Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 12 GLOBAL MUSIC TRAITS AFRICA Dynamics Traditional community based music requires projection. Loud dynamics created through multi-part ensembles, full voices, and buzzing devices added to instruments. Medium Vocals tend to predominate. Instruments depend on region and specific genre. Bell oriented drum ensembles in west Africa. Mbira in Zimbabwe. Kora, kontingo or balo among Manding jali. Duration Tempo Little tempo change. Tempo is often determined by specific dances. Meter Polymeter Rhythmic patterns Often asymmetric groupings of 2s and 3s. Ensembles are usually polyrhythmic. Pitch Scales Scales and intonation are variable and dependant on culture. Variations within cultures also occur. Melody Often repetitive with subtle variations. Melodies sometimes created through interlocking parts. Instrumental and vocal melodies often follow speech tones of associated text. Chords In general, music is constructed in polyphonic layers without European notions of harmony. Ghanaian melodies are often harmonized in 3rds due to European influence. Chord progression and tonality Mbira music has non-Western harmonic movement. Texture Usually multipart (not just melodic but also percussion-based) and polyphonic. Ostinato often underlies melodies. Forms Call and response is common. Bell based polymetric percussion ensembles associated with west Africa. Manding jali music influenced blues and jazz form of repetitive sections interspersed with improvised sections. Length of performances and improvisations are variable due to requirements of the occasion. Composers Music is often passed down through oral tradition either through hereditary music specialists or communal transmission. The original composers are not known in most traditional music. This is not so true in contemporary popular music. While the basic composition may be traditional, master musicians often add their own variations and embellishments suited to the performance context. Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 13 ANDEAN SOUTH AMERICA Dynamics Not emphasized in folk traditions but may be used for effect in modern folk arrangements. Medium Pre-European music includes vocal, percussion, flutes, and large panpipe ensembles. The harp and guitar were introduced by the Spanish. Mestizo music often includes European band instruments for festival processions. Duration Tempo Many types of music are played at tempi appropriate to specific dances. Meter Juxtaposed or alternating meters of 6/8 and 3/4 are characteristic of mestizo music. Rhythmic patterns Rhythmic patterns often distinguish dance genres such as sanjuan and wayno. African influenced music tends to have more rhythmic layering. Pitch Scales Variable. Alternation of major and minor scales within a song is a common characteristic of mestizo music. Tuning variances in traditional ensembles result in a slight dissonant quality of sound. Melody Traditional songs tend to include much repetition. Chords Panpipe ensembles will often play in parallel 4th and 5th. Mestizo music tends to harmonize in 3rds and follow European chord movement. Tessitura Tends to be high. Texture Can range from large homogenous panpipe ensembles playing in parallel motion to monophonic vocal or instrumental melodies with or without percussion. May or may not include chordal accompaniment on guitar or charango. Mestizo music tends to harmonized. Forms Dependant on region and associated dances or other genres. Tends to be strophic. Composers Traditional musicians may perform their own compositions. Contemporary folk ensemble may perform traditional songs without a known composer or perform works of more contemporary composers. Composers of the nueva cancion movement provided many songs with lyrics about social injustices performed in a traditional style to show solidarity with the common people. Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 14 INDIA CLASSICAL MUSIC Dynamics Dependant on artistic expression of performer Medium A basic ensemble consists of 1-2 melodic soloists (vocal and/or instrumental), 1-2 percussionists, drone source (tambura or electronic) Duration Tempo Long concert forms tend to get progressively faster Meter Rhythm is organized by tala cycles. Alap (alapana) is unmetered. Rhythmic patterns Drummers learn patterns specific to each tala before embarking on improvisations. Melodic/rhythmic patterns of three usually indicate a cadence. Pitch Scales Ragas are classified in part by scale but several ragas may use the same note inventory. A typical raga averages about 7 pitches. Intonation is variable, especially in Hindustani music. Melody Melody is influenced by melodic ideas, specific ornamentation, and pitch hierarchy particular to the raga being performed. Light classical forms may use folk melodies. Chords Indian music emphasizes melodic development rather than harmony. The drone provides a tonal reference for interval intonation and a tonal center. cadences Endings are signaled by patterns repeated three times. Texture Usually monophony with an underlying drone (i.e., diaphony). When there are two melodic performers they either play in unison, alternate solos, or one shadows the other. Forms In general, long concert forms progress rhythmically from unmetered to pulsed to metered by tala. The most common Carnatic concert form is the kriti, a three part religious song. Through improvisations this form can be expanded. The most common instrumental concert form of the Hindustani tradition is alap-jor-jhalla-gat. Composers Hindustani melodies are usually passed down from guru to student. Instrumental melodies may not have a name. Carnatic melodies tend to be songs by known composers. The best known composers of kriti are Shyama Shastri, Tyagaraga, and Muttuswami Dikshitar. Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 15 INDONESIA Dynamics Balinese gamelan kebyar has abrupt dynamic changes within the same piece. Javanese gamelan has soft style and loud style pieces that have few dynamic changes. Medium Gamelan ensembles, Balinese kecak. Duration Tempo Balinese gamelan kebyar may have abrupt tempo changes. Javanese tempo changes are less frequent and are accomplished through irama changes in which the pulse doesn't change but the space between balungan notes changes. Tempo changes are initiated by the drummer. Meter Concepts of meter don't apply. A melody is filled in with patterns in multiples of 4 pulses dependant on irama level. Pitch Scales Two scales types exist in gamelan: pelog (7 tone) and slendro (5 tone). The actual interval sizes and pitch vary from ensemble to ensemble. Melody Melody lengths are determined by form and must conform to modes. Embellishments of melodies come from standard patterns unique to each instrument. Final cadences Endings are signaled by the drummer and are marked by the large gong. Texture Gamelan texture is heterophonic in concept but this is not apparent to the new listener. Each instrumentist interprets the melody in idioms appropriate to his instrument. Melodies are punctuated by instruments of the gong family. Forms Form is determined by the length of the melody and how that melody is punctuated by gongs. Some forms are composed for specific dance choreographies. Composers Many traditional pieces have been passed down aurally without a known composer. From the 20th century to the present many new pieces have been composed. Some composers stay in traditional forms while others experiement in new styles. Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 16 JAPAN Dynamics Dynamics in ensemble playing such as the gagaku ensemble are often a matter of how many instruments are playing at one time. In solo or small ensemble playing dynamic changes can occur in subtle ways, e.g., the swells heard on single notes of the shakuhachi. Medium Traditional music can encompass vocal and instrumental soloists or ensembles. In general, ensembles include a balance of instruments of unique timbre rather than a more homogeneous sound such as that found in a string-biased symphony orchestra. Instruments most associated with the Edo period include koto, shakuhachi, and shamisen. Duration Tempo A flexible pulse is characteristic. The aesthetic of jo-ha-kyu includes an increase in tempo as the piece proceeds, but this is usually subtle. Meter Duple meters predominate, but much music is unmetered or flexible. Rhythmic patterns Percussion instruments in gagaku play stereotyped rhythmic patterns particular to each instrument. Pitch Scales Scales are diverse and dependant on genre. Pentatonic scales are most common. Intonation is traditionally variable but has moved toward European equal temperament. Melody Most traditional melody is composed but often gives the impression of natural spontaneous expression. Timbre Timbre is important to the Japanese aesthetic. Music often emphasizes changes and contrasts in timbre through instrumentation or techniques on individual instruments or voices. Harmony Functional harmony not present but chord clusters exist in the sound of the sho. Genres Very diverse and a reflection of the influences on Japanese culture. Gagaku developed from Chinese and Korean court music. Shakuhachi music was originally associated with Zen monks. Shamisen has folk origins, but is also essential to many types of Edo period styles such as teahouse music (e.g. kouta), kabuki theater, and bunraku. Modern music is a mix of Western and Japanese elements (e.g., enka) or purely Western in origin. Taiko is a 20th century mix of old instruments and aesthetics with new. Texture Monophonic or heterophonic. Slight delays of phrasing between the shamisen and voice emphasizes the unique sound of each. Gagaku music is comprised of heterophonic melodies performed by aerophones with punctuated points of emphasis played on chordophones, idiophones, and membranophones. Forms Idiomatic to each genre. Jo-ha-kyu (exposition-development-speed up to the end) structure is common. Composers Many traditional compositions are attributed to the masters and founders of guilds. New compositions were discouraged in traditional Japan. Modern Japan has many composers of very diverse styles. Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 17 Stylistic Trait Inventory Piece: _____________________________________ Composer: ______________________ Date: _____________ Period:_________________________ Medium: voice, choir, orchestra, solo keyboard, voice and piano, string quartet, piano quintet, other:______ Genre: sacred, secular, choral, vocal, instrumental, symphonic, operatic, chamber music, other:____________ Texture: monophonic heterophonic homophonic (block chords, melody and accompaniment) polyphonic (imitative, non-imitative) Dynamics: none indicated, terraced, abrupt changes, gradual changes, extreme contrast Duration Tempo: none indicated, slow/medium/fast, changes within piece, extremes, detailed instructions Meter: none indicated, duple/triple, simple/compound, ametric/ metric, complex, changing, polymetric Patterns: none, patterns of long/short, pattern length (beat, measure, phrase) Sub-divisions of beat: 2’s, 3’s, 4’s, 5’s, 7’s etc Syncopations Pitch Scale basis: modal, diatonic, chromatic, pentatonic, 12-tone row, pitch-set, octatonic Chord type(s): perfect intervals triadic, seventh chords, extended tertian, altered, added notes quartal, clusters degree of tension: consonant/dissonant Chord progression/harmonic movement: functional (I-IV-V-I type progressions), root movements by 2nds or 3rds or 5ths, harmonic rhythm (regular/irregular, fast/slow) Cadences: perfect/imperfect authentic, plagal, Landini, step-wise, deceptive, incomplete Tonality: beginning and ending on same/different pitch centers, modulations, atonal, polytonal Melody/phrase: Relationship between notes (conjunct/disjunct) Range (narrow/wide) Complexity (simple/ornamented) Phrases (symmetrical/irregular, antecedent/consequent) Construction (motivic, sequential) Character (vocal/instrumental, lyric, gestural, virtuosic) Text Language (Latin, Italian, French, German, English, etc.) Type (mass: ordinary/proper, poetry, prose) Relationship of text to music: syllabic/melismatic text-painting strophic/through-composed Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 18 MU 370 Music Literature Proficiency Sample Exam Name:__________________________________ Describe stylistic elements for each of the ten selections of music . You may use short answer or single words if appropriate. You do NOT need to include details for every category listed, but you should include at least five accurate observations for each selection, observations that lead you to make an educated placement within a style period and types of music. After listing stylistic elements, identify a probable date of composition (or within a musical stylistic period). a probable composer active during the time period and writing the particular genre. a probable genre or form of composition. For non-western music (from Global Music), provide a probable geographical area and genre. Grading: Each example is worth 10 points. You may earn up to 5 points for accurately describing appropriate stylistic elements, 1 point for each accurate statement. You may earn up to 5 points for placing the selection within an appropriate historical context. 2 points for each accurate statement. Credit will not be given for conflicting answers unless you provide specifics. For example, you will not receive credit for placing a piece in both the baroque and contemporary eras, unless you clearly state which elements point to the baroque era and which point to the contemporary. You will need to earn at least 30 points out of a total of 50 points to pass the listening part of the proficiency. You will need to earn at least 30 points out of a total of 50 points to pass the written part of the proficiency. Listening Examples Each will be played twice. The length of the selection is given as well as if the selection is complete or an excerpt. Written Examples Each selection is noted if it is complete or an excerpt. Feel free to label noteworthy details on the score. Aural Example 1 Duration: 1’52”. Complete selection. Description of music’s features Medium Texture Dynamics Duration (Tempo \ Meter \ Patterns) Pitch (Scale basis \ Melody/phrase \ Chord type(s) \ Chord progression - harmonic movement \ Tonality Place in History and Culture Likely date of composition: Likely stylistic period: Likely composer: Likely genre/form: Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 19 Marylhurst University Department of Music July 18, 2011 Page 20