Common issues for tenants

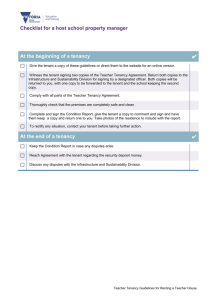

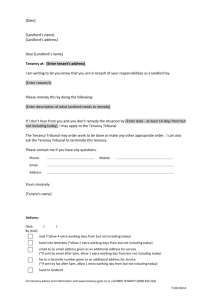

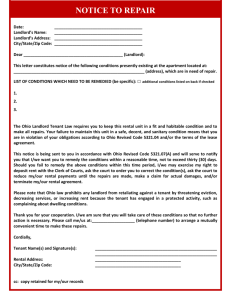

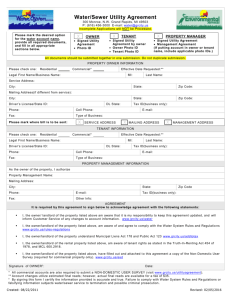

advertisement