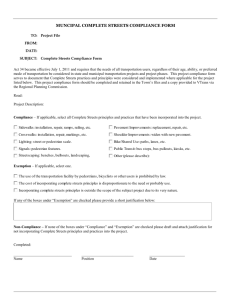

Missouri Livable Streets

advertisement