Journeying out of silenced familial spaces

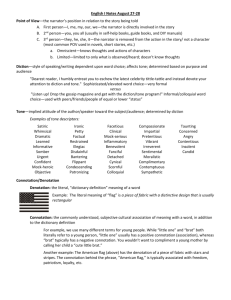

advertisement