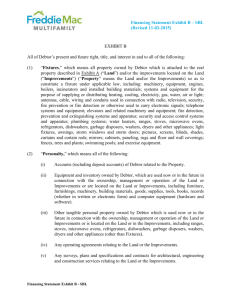

the 2010 amendments to ucc § 9-503: sufficiency of

advertisement