Case No. 13-8618 ROBERT MARK EDWARDS, Petitioner, vs

advertisement

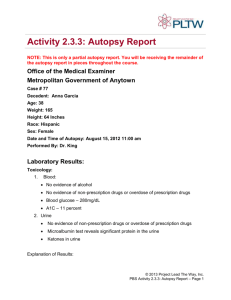

Case No. 13-8618 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES ROBERT MARK EDWARDS, Petitioner, vs. STATE OF CALIFORNIA, Respondent. On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of California REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONER Quin Denvir Counsel of Record State Bar No. 49374 1614 Orange Lane Davis, CA 95616 Telephone:(916) 307-9108 Attorney for Petitioner Robert Mark Edwards TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............................................................................iii REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONER ................................................................. 1 CONCLUSION................................................................................................ 16 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Crawford v. Washington, 541 U.S. 36 (2004)........................................................................................7 Gamache v. California, ___ U.S. ___, 131 S. Ct. 591 (2010) ..........................................................13 Malaska v. State, 2014 WL 808164 (Md. Ct. Spec. App. Feb. 28, 2014) ................................6 People v. Aranda, 55 Cal. 4th 342, 283 P.3d 632 (2012) ........................................................13 People v. Dungo, 55 Cal. 4th 608, 266 P.3d 442 (2012).......................................................4, 6 People v. Edwards, 57 Cal. 4th 658, 306 P.3d 1049 (2013).........................................................6 People v. Jackson, 2014 WL 825247 (Cal. Mar. 3, 2014) ........................................................13 People v. Pearson, 56 Cal. 4th 393, 297 P.3d 793 (2013)...........................................................7 People v. Rodriguez, 2014 WL 655994 (Cal. Feb. 20, 2014).........................................................6 People v. Whitt, 51 Cal. 3d 620, 798 P.2d 849 (1990)..........................................................13 State v. Griep, 2014 WL 625743 (Wisc. Ct. App. Feb. 19, 2014) .......................................6 State v. Mecier, 2014 WL 712660 (Me. Feb. 25, 2014) .........................................................6 iii Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S. 288 (1989)......................................................................................7 Whorton v. Bockting, 549 U.S. 406 (2007)......................................................................................7 Williams v. Illinois, ___ U.S. ___, 132 S. Ct. 2221 (2012) ..........................................................6 Statutes Cal. Gov’t Code § 27491 ...................................................................................2 Cal. Gov’t Code § 27491.1 ................................................................................2 iv REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONER The State’s Brief in Opposition (BIO) fails to detract from the compelling reasons why certiorari review is warranted to resolve whether statements in an autopsy report created as part of a homicide investigation and concluding that the nature and extent of the death and injuries sustained by the homicide victim were caused by criminal conduct are testimonial. Nor do the State’s quibbles with the procedural history and record diminish the suitability of this case as a vehicle for resolving the issue. The petition for certiorari should be granted. 1. The State court ignores the basic constitutional premise set forth in the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari (“Petition”) that governs this case: statements contained in an autopsy report created as part of an investigation of a death that obviously was a homicide, and prepared for the purpose of establishing criminal liability, are testimonial. Instead, the State urges the Court to deny the Petition, asserting that the question whether statements in an autopsy report are testimonial is an “inherently fact bound” inquiry that requires no resolution of law by the Court. The State further argues, incorrectly, that under its “fact bound” rubric, the statements in the autopsy report in this case are not testimonial because the “primary purpose” for autopsies in California is not criminal investigation. The State’s central argument that the autopsy report in this case, and the statements contained therein, were not testimonial because “the primary purpose of 1 autopsies in California is not criminal investigation” (BIO 18, 26, see also BIO 19, 20) fails for two important reasons. First, although California Government Code section 27491 applies also to certain types of deaths other than homicides, section 27491.1 specifically directs that autopsies be prepared in cases involving suspected homicides and expressly mandates that the coroner perform investigative and reporting duties in such cases. Cal. Gov’t Code § 27491 (enumerated circumstances in which coroner is required to investigate include “known or suspected homicide, suicide, or accidental poisoning” and “deaths under such circumstances as to afford a reasonable ground to suspect that the death was caused by the criminal act of another”); Cal. Gov’t Code § 27491.1 (specifying the duties of the coroner when “person has died under circumstances that afford a reasonable ground to suspect that the person’s death has been occasioned by the act of another by criminal means”). 1 Respondent’s assertion that “the scope of the coroner’s statutory duty to investigate is the same, regardless of whether the death resulted from criminal activity” (BIO at 25) is thus inaccurate. 1 Section 27941.1 requires the coroner “to immediately notify the law enforcement agency having jurisdiction over the criminal investigation when a person has died under circumstances that afford a reasonable ground to suspect that the person’s death has been occasioned by the act of another by criminal means.” That report to law enforcement must state, besides the name of the decedent and the location of the remains, “other information received by the coroner relating to the death, including any medical information of the decedent that is directly related to the death.” Ibid. Appendix C to the petition is the report required by Section 27941.1 in Ms. Deeble’s case. 2 Second, as to the primary purpose, the state court’s premise was that “criminal investigation was not the primary purpose for the autopsy report’s description of [the victim’s] body; it was only one of several purposes.” People v. Dungo, 55 Cal. 4th 608, 620 (2012). “The autopsy report continued to serve several purposes, only one of which was criminal investigation.” Id. at 621. However, the fact that the report may have served other purposes2 does not mean that criminal investigation was not its primary purpose. 3 In this regard, the Court has held that, “in identifying the primary purpose of an out of court statement, we apply an objective test. [Citation] We look for the primary purpose that a reasonable person would have ascribed to the statement, taking into account all of the surrounding circumstances.” Williams v. Illinois, __U.S.__, 132 S.Ct. 2221, 2 The other “purposes” described by the court are better termed “uses”: “The usefulness of autopsy reports, including the one at the issue here, is not limited to criminal investigation and prosecution; such reports serve many other equally important purposes. For example, the decedent’s relatives may use an autopsy report in determining whether to file an action for wrongful death. And an insurance company may use an autopsy report in determining whether a particular death is covered by one of its policies. [Citation] Also, in certain cases an autopsy report may satisfy the public’s interest in knowing the cause of death, particularly when (as here) the death was reported in the local media. In addition, an autopsy report may provide answers to grieving family members. 3 “Primary” means “of chief importance, (www.oxforddictionaries.com), not “sole” or “exclusive.” 3 principal” 2243(2012). Taking into account all the circumstances of the Deeble autopsy, a reasonable person would have understood its primary purpose as criminal investigation. There is no dispute that Dr. Robert Richards, the pathologist who performed the autopsy in this case, understood that the victim’s death was a homicide when he conducted the autopsy and prepared the autopsy report at the direction of, and in concert with, law enforcement personnel.4 As set forth in the Petition, several features of the autopsy report indicate that its primary purpose was to facilitate a criminal investigation, including that it was completed on the Orange County Sheriff’s Department letterhead, contained the sheriff department’s case number for the homicide investigation on each of its pages, and several law enforcement officers were listed on the report as “autopsy witness[es]” (three sheriff’s deputies and two detectives investigating the homicide, a criminalist who investigated the crime scene, and a deputy coroner from the Sheriff-Coroner’s office). Pet. at 3-4. Moreover, all of the statements in the autopsy report that are at issue in this case were produced to establish criminal liability; that is, they established that the death was a homicide and/or that a perpetrator inflicted particular injuries relevant 4 Prior to conducting the autopsy and creating the report, Dr. Richards obtained information confirming that the victim died as the result of a homicide, including information that there were ligatures around the victim’s neck and wrists and law enforcement officers informed Dr. Richards that the victim was found hanging by her neck with a belt ligature attached to a dresser drawer. 4 to specific criminal liability. The statements at issue thus clearly “pertain to criminal prosecution.” The statement regarding the cause of death – asphyxiation due to ligature strangulation – clearly indicates criminal conduct, as do the statements about many of the victim’s other alleged injuries. For example, the critical hearsay statements from the autopsy report admitted through the testimony of Dr. Richard Fukumoto -- the pathologist who was not present at and did not perform the autopsy -- were conclusions concerning criminal activity: • The lacerations on the victim’s right ankle were caused by two wires, RT 2129-30 (testifying that Dr. Richards described “something [] scratched the surface of the skin . . . . caused by wires probably coming together and inflicting the injury”), 5191-92 (“There were ligature marks on the ankles . . . . caused by a blunt instrument with a[n] . . . edge”); • The alleged injury to the victim’s left ear drum was caused by a sharp instrument, RT 2127 (“incision . . . caused by sharp instrument or an instrument that has a point”), 5189; • The victim’s fractured nose suggested physical violence, RT 2130-31, 5333 (testifying that fracture of her nasal bone was evidence of blunt trauma), 5197 (discussing the “blow” to the nose); 5 • Residue on the victim’s face came from adhesive tape, RT 2160-61, 5197; • The victim’s alleged vaginal and anal injuries resulted from sexual assault, RT 2137-38, 2147-48, 5195-96. The State, in large part simply repeating the California Supreme Court’s conclusions in People v. Dungo, 55 Cal. 4th 608, 266 P.3d 442 (2012), argues that most of the above hearsay statements are not testimonial because they are simply “anatomical and physiological observations about the condition of the body,” “comparable to observations made by an examining physician for treatment purposes.” BIO at 23-24 (quoting Dungo, 55 Cal. 4th at 619); see also BIO at 26. The State, however, fails to explain how the conclusions included in these hearsay statements set forth above, which indicate criminal activity and thus pertain to criminal prosecution, are analogous to observations a physician would make when treating a patient. As the above examples demonstrate, the California Supreme Court’s distinction between objective anatomical observations and forensic conclusions, adopted by the State in the BIO, “is too amorphous to be workable” and has no merit. See Pet. at 14-19 (quoting People v. Edwards, 57 Cal. 4th 658, 774, 306 P.3d 1049 (2013) (Corrigan and Liu, JJ., concurring and dissenting)). Critically, in this case the “observations made by an examining physician” were 6 not made “for treatment purposes,” but rather to facilitate the criminal investigation and prosecution. BIO at 23-24 (quoting Dungo, 55 Cal. 4th at 619). 2. Although the State acknowledges that state and federal courts “have reached different results in addressing the admissibility of [ ] autopsy reports under the Confrontation Clause,” the State asserts that the split does not reflect a conflict in interpretation of law that requires this Court’s resolution. BIO at 17. The State is mistaken. This case presents an ideal vehicle for resolving the increasingly divergent decisions in federal and state courts on whether hearsay statements in an autopsy report are testimonial statements subject to the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment, a conflict that has persisted in the wake of this Court’s plurality opinion in Williams v. Illinois, ___ U.S. ___, 132 S. Ct. 2221 (2012). There is a live controversy on this issue and an urgent need to resolve the conflict. Indeed, since the Petition was filed in this case, at least three state decisions have issued that further illustrate the depth of the disagreement across the country on the questions presented. See Malaska v. State, 2014 WL 808164 (Md. Ct. Spec. App. Feb. 28, 2014) (holding autopsy report to be sufficiently formalized to be testimonial for purposes of the Confrontation Clause); State v. Mecier, 2014 WL 712660 (Me. Feb. 25, 2014) (holding that the admission of testimony of a medical examiner who did not conduct autopsy did not violate the Confrontation Clause); People v. Rodriguez, 2014 WL 655994 (Cal. Feb. 20, 2014) (applying the same 7 logic of the court’s direct appeal opinions in Dungo and Edwards and holding that testimony regarding statements from an autopsy report by a pathologist who did not conduct the autopsy did not violate the Confrontation Clause because the statements described “objective facts about the condition of the victim’s body” and were not prepared for the primary purpose of furthering a criminal investigation). An additional state decision has issued since the filing of the Petition related to the question presented regarding surrogate expert testimony. See State v. Griep, 2014 WL 625743 (Wisc. Ct. App. Feb. 19, 2014) (noting that surrogate expert testimony “in effect put[s] the statements in the report into evidence” even where the report at issue is not admitted into evidence). /// /// /// /// /// /// /// 8 3. The State’s assertions that this case is an inappropriate vehicle for resolving this important issue are disingenuous. The State argues that this case is a poor vehicle procedurally because the trial occurred before this Court’s opinion in Crawford v. Washington, 541 U.S. 36 (2004), and Petitioner’s trial counsel failed to preserve the issue by failing to object to Dr. Fukumoto’s testimony on Confrontation Clause grounds. 5 6 There is no dispute that Crawford (and this Court’s cases applying Crawford) apply retroactively to cases on direct review, 7 and it has been clearly established that a defendant’s failure to object to preCrawford Confrontation Clause violations is excused because counsel cannot be faulted for failing to anticipate the change in the law in Crawford. See, e.g., People v. Pearson, 56 Cal. 4th 393, 461-62, 297 P.3d 793 (2013) (applying 5 The State concedes that the California Supreme Court rejected this argument and ruled that counsel’s failure to object was no obstacle to that court’s consideration of Petitioner’s federal claim. BIO at 10 and n.5. It should be no obstacle to this Court’s consideration of the claim. 6 Respondent states that the record before this Court might have been different if there had been a defense objection at trial. The suggestion is fanciful. Armed with a California Supreme Court decision which upheld the admissibility of testimony by Dr. Fukumoto regarding hearsay statements from a different autopsy report prepared by a different autopsy surgeon, People v. Beeler, 9 Cal. 4th 953, 979 (1995), it is hardly likely that the prosecution would have done any more than cite that controlling decision if the defense had objected. 7 See Whorton v. Bockting, 549 U.S. 406, 416 (2007) (noting that under Teague v. Lane, 489 U.S. 288 (1989), the rule announced in Crawford is applicable on direct review). 9 Crawford retroactively and holding that defendant did not forfeit constitutional claim by failure to object on Confrontation Clause grounds). This case is an ideal vehicle to resolve the questions presented because the lower court’s opinion is illustrative of the live controversy, with two justices concluding in a thoughtful dissent that the autopsy report statements at issue in this case were testimonial and their admission was prejudicial, and presents a legal framework that contravenes this Court’s precedent and employs illogical and unworkable distinctions in application. As set forth in the Petition, the California Supreme Court’s approach is misguided and constitutionally invalid. See Pet. at 14-20. 4. The State’s final argument – that this case is a poor vehicle for resolving this conflict because any error was harmless – lacks merit. BIO at 28-30. As a threshold matter, no proper harmless error analysis has ever been conducted in this case. The California Supreme Court misinterpreted the scope of the Confrontation Clause violations and, as a result, improperly limited its harmless error analysis to only two statements in the autopsy report. Pet. at 17-18 (state court’s prejudice determination constrained by its conclusion that the introduction of Dr. Fukumoto’s testimony regarding the cause of death and the marks on the ankles resulted from its invalid conclusion that most of the statements in the autopsy report recounted by Dr. Fukumoto were not testimonial). 10 The State argues that any violation of the Confrontation Clause was harmless because Dr. Fukumoto formed the opinions presented in his testimony independently. 8 As set forth in the Petition, the California Supreme Court mischaracterized a number of Dr. Richards’ forensic opinions and conclusions as “objective facts” and failed to recognize that Dr. Fukumoto did not form, and could not have formed, his opinions independently because there was no nonhearsay basis available for much of Dr. Fukumoto’s testimony. Pet. at 19. Contrary to the State’s assertion, the record does not establish that Dr. Fukumoto “formed his opinions independently after reviewing the autopsy report, photographs, microscopic slides, and x-rays taken during the autopsy.” BIO at 5, 18-19. 9 As a general matter, Dr. Fukumoto testified that Dr. Richards failed to make microscopic slides or take photographs of many of the injuries he reported. RT 2152 (no microscopic slide of alleged ear drum injury), 2162-63 (no microscopic slide of alleged nose fracture), 5199 (no photograph or slide of ear 8 The State also argues that the purportedly independent basis for Dr. Fukumoto’s opinions distinguishes this case from the cases Petitioner presented where statements in an autopsy report were found to be testimonial, BIO at 16-20, and immunizes his testimony from violating the Confrontation Clause. These arguments lack merit for all the reasons set forth above. See also n.6, infra. 9 Moreover, as set forth in the Petition, Dr. Fukumoto’s “seeming concurrence” with Dr. Richards’ hearsay statements, based on his review of slides and photographs, exacerbated the prejudice to Petitioner of Dr. Fukumoto’s unconstitutional surrogate testimony by “bolster[ing] his own credibility based on hearsay not subject to cross-examination.” Pet. at 18 (quoting Edwards, 57 Cal. 4th at 773 (Corrigan and Liu, JJ., concurring and dissenting) (internal quotation marks and citation omitted)). 11 drum), 5201-02 (no microscopic slides, measurements, or adequate photographs of alleged genital lacerations). With regard to specific injuries, Dr. Fukumoto admitted that he was unable to observe the “incisional” injury to the ear drum to which Dr. Richards referred in the autopsy report because the ear drums that Dr. Richards purportedly removed from the body were either “lost or misplaced” and he failed to make microscopic slides or take photographs of the specimen, RT 2152, 5198-200; he relied entirely on Dr. Richards’ description of the adhesive residue, not on any photographic evidence, RT 5197, RT 2160-61; and he was unable to observe the alleged laceration injuries to the victim’s genitalia because Dr. Richards failed to make microscopic slides, take adequate photographs, or provide any measurements of the reported injuries, RT 5201-02. Although Dr. Fukumoto clearly and repeatedly stated on the record that he did not have an independent basis for many of the opinions presented through his testimony, the State nevertheless erroneously asserts that these opinions had an independent, non-hearsay basis. For example, the State asserts that Dr. Fukumoto relied upon his examination of an x-ray of the victim’s nose for his testimony that her nose was fractured. BIO at 22, 27. But Dr. Fukumoto testified he was not qualified to read the x-ray image. RT 2142. The State also contends that Dr. Fukumoto’s opinion that the reported vaginal and rectal injuries occurred before death was based upon his “personal[] stud[y]” of the 1986 microscopic slides. BIO 12 at 7. But Dr. Richards did not create a slide of anal tissue, and “[n]o tissue response is noted” in the single slide of vaginal tissue produced. See CT 658-59.. The State contends that Dr. Richards described x-rays in his autopsy report, providing a foundation for Dr. Fukumoto to form independent opinions. BIO at 2. In fact, in the section entitled “X-ray” of the autopsy report, Dr. Richards noted the “x-rays show nothing of pertinence save for the extensive dental work” and he did not include a description of any x-ray that could have supported any portion of Dr. Fukumoto’s testimony at issue. Appendix (App.) C at 2 (describing x-ray showing wrist ligatures and belt buckle and dresser handle attached to neck ligature). When all of the testimonial statements from the autopsy report are properly considered, it is clear that their admission at the guilt trial and second penalty trial was extremely prejudicial to Petitioner. The statements admitted in violation of the Confrontation Clause provided the primary foundation for the theories of firstdegree felony murder and both special circumstances (torture murder and burglary murder), and had no evidentiary basis other than Dr. Richards’ autopsy report. Dr. Fukumoto’s testimony relaying the autopsy report statements constituted the only evidence of the victim’s injuries, the pain the victim may have experienced, and sexual assault. The State ignores Petitioner’s arguments regarding the unconstitutional admission of testimonial statements regarding the victim’s alleged vaginal and anal 13 injuries. See, e.g., Pet. at 7-10 (describing Dr. Fukumoto’s testimony regarding vaginal and anal injuries “consistent with” sexual assault with a mousse can, the prosecution’s heavy reliance on the alleged sexual assault in its case for torture, and Dr. Fukumoto’s admission that his testimony regarding the genital injuries relied entirely upon hearsay statements from the autopsy report because the injuries were not visible in photographs or microscopic slides produced during the autopsy). Indeed, the State does not contest that the only evidence of sexual assault was admitted in violation of the Confrontation Clause. Dr. Fukumoto’s testimony regarding the alleged vaginal and anal injuries, and their consistency with a mousse can, relied wholly on Dr. Richards’ testimonial statements in the autopsy report describing genital lacerations and injuries not measured nor documented in any autopsy photographs or microscopic slides. Even the prosecutor conceded, in his closing argument at the guilt phase, that the genital and anal injuries were only “visible to Dr. Richards’ [sic] eyes.” RT 2934. Without the evidence of sexual assault, the State lacked the evidence for torture-murder or burglary felony-murder based upon intent to commit sexual assault, as well as the evidence underlying both the special circumstances. Even if this Court determines that other evidence presented at trial supports a burglary-based first-degree murder theory and special circumstance, the prosecution’s introduction of testimony regarding statements in the autopsy report 14 had a prejudicial effect on the jury’s determination at the sentencing phase. This is a case where these statements may have made the difference between life and death. The jury failed to reach a verdict on the penalty decision at Petitioner’s first trial. The prosecution knew that the emotional impact of Dr. Richards’ statements about the victims’ injuries was critical to obtaining a death sentence. In his closing argument at the second penalty trial urging the jury to return a death verdict, the prosecutor relied substantially on Dr. Fukumoto’s unconstitutional testimony about Dr. Richards’ statements regarding the victim’s injuries. RT 6414-15. Absent Dr. Fukumoto’s testimony about these injuries and the prosecutor’s related arguments, the jury may not have sentenced Petitioner to death. The State’s assertion that Petitioner suffered no prejudice as a result of the unconstitutional admission of Dr. Fukumoto’s testimony is flawed for another reason. As Justice Liu recently explained in his dissent in another California capital case, the California Supreme Court’s formulation of Chapman harmless error analysis, which it applied in this case, contravenes this Court’s precedent. See People v. Jackson, 2014 WL 825247, *33-36, *45-60 (Cal. Mar. 3, 2014) (Liu, J., dissenting). 10 10 Justice Liu opined, as four members of this Court concluded in a statement respecting the denial of certiorari in Gamache v. California, ___ U.S. ___, 131 S. Ct. 591 (2010), the California Supreme Court’s application of the Chapman harmless error standard improperly places the burden of persuasion on the defendant. Jackson, 2014 WL at *33, *58; see also People v. Aranda, 55 Cal. 4th 15 CONCLUSION For the foregoing reasons, the petition for a writ of certiorari should be granted. Dated: March 24, 2014 Respectfully submitted, By: Quin Denvir Counsel of Record 1614 Orange Lane Davis, CA 95616 Telephone: (916) 307-9108 Attorneys for Petitioner Robert Mark Edwards 342, 379, 383, 283 P.3d 632 (2012) (Liu, J., concurring and dissenting) (noting that the majority found the omission of an instruction to be harmless under Chapman despite the state’s concession in its answer brief that the error required reversal). The California Supreme Court’s jurisprudence further ignores the fact that it is the state’s burden to prove that the error was not harmless by repeatedly inferring that there is no reasonable possibility of prejudice where the record is silent or indeterminate as to actual prejudice. See, e.g., People v. Whitt, 51 Cal. 3d 620, 798 P.2d 849 (1990) (explaining that the Chapman standard creates a strong presumption that the defendant was prejudiced where prejudice can be assessed from the record and finding no prejudice where the record was silent as to prejudice); Jackson, 2014 WL at *58 (describing the state court’s “recurring maneuver” in its harmless error jurisprudence of “infer[ring] no reasonable possibility of prejudice where the record is silent or indeterminate as to actual prejudice”). 16 CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE I certify that the attached petition for writ of certiorari is proportionately spaced, has a typeface of 13 points or more and contains approximately 3,522 words. Date: March 24, 2014 _______________________ Quin Denvir Attorney for Petitioner Robert Mark Edwards 17 PROOF OF SERVICE I am a citizen of the United States and a resident of Sacramento County. I am over the age of eighteen years and not a party to the within above-entitled action; my business address is Rothschild Wishek & Sands LLP, 765 University Avenue, Sacramento, California 95825. On the below named date, I served the within REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONER People v. Edwards Case No. S073316 On the parties in said action as follows: XXX (By REGULAR MAIL) by placing a true copy thereof enclosed in a sealed envelope with postage thereon fully prepaid, in the United States post office mail box at Sacramento, California, addressed as follows: Deputy Attorney General Arlene A. Sevidal 110 W. A Street, #1100 Box 85266 San Diego, CA 92186-5266 Robert Edwards CDC No. P-11700 San Quentin State Prison San Quentin, CA 94974 I, Geena Renda, declare under penalty of perjury that the foregoing is true and correct. Executed this 24th day of March, 2014, at Sacramento, California. __________________ Geena Renda 18