Humphreys, K. L., †Katz, S. J., Lee, S. S., Hammen, C. L., Brennan

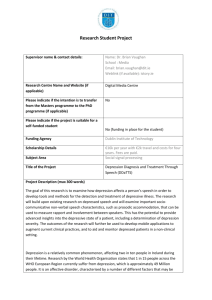

advertisement