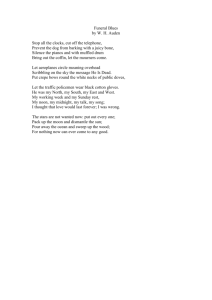

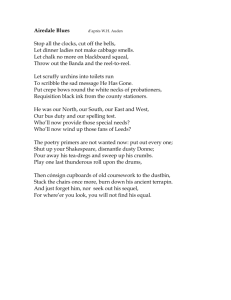

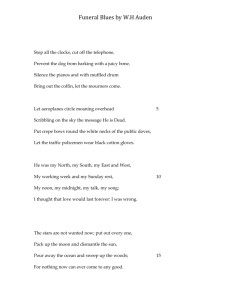

W.H.Auden

advertisement

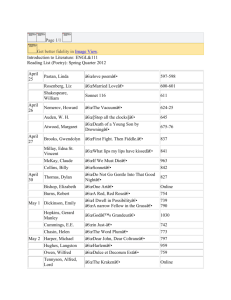

Alex Weathersby English/Irish Poetry Dr. Drummond December 7, 2008 A Remarkable Critic “The Fall of Rome” fits almost perfectly into the typical thematic framework of his early work of the late 1920’s through the 1930’s despite its having been written postWorld War II, and after Auden’s move to the United States. In “The Fall of Rome,” Auden draws connections between the decline of the Roman Empire and what he views as the utter hypocrisy and backwardness of contemporary society. He does this through juxtaposition of contrasting ideals that are illustrated through brief but powerful images. Each stanza contains another picture of the declining Roman society, and therein another societal criticism. “The Fall of Rome” is as clear an example as any other of the societal perspective and social criticism that are so prevalent in Auden’s early work, and his feeling that his contemporary society is corrupt and diseased, and that it lacks any forward progression, are all expressed with beautiful, specific images, which represent a larger theme of social stagnancy. Auden’s theme of societal inability to progress is expressed in the first stanza through a series of brief images much like those he uses throughout the entire poem to convey his intended meanings. The images found in the first stanza will set the tone for the rest of the poem, and Auden therefore chooses pictures that feel tired and desolate. He creates a storm by describing the sea: “The piers are pummeled by the waves” (Ricks 609). This creates a mental image of constant, persistent testing of man’s creation by natural forces. Having just come from the Second World War and the Great Depression, England must surely have felt as though it was constantly being battered, both from the Weathersby 2 inside and out, and Auden captures this with his first line. The next image he creates is one that expresses, with an incredible poetic beauty, Auden’s feelings about society’s position: “In a lonely field the rain / Lashes an abandoned train” (609). This picture is a direct description of Auden’s view of society’s lack of movement. The image of the “abandoned train,” sitting “In a lonely field” to be battered by a downpour is an image of a machine that is designed for progress, industry and improvement that has been completely ignored and allowed to sit in a time of complete stagnancy. It also seems likely that this image is one which describes Auden’s feelings of societal stagnancy due to the obvious lack of locomotives early in the first millennium A.D., and because he is describing Rome—at least on the surface—this image is quite clearly one which describes a sentiment or social phenomenon that Auden has observed. The final line and image is one of foreboding, and one which describes Auden’s feeling of constant threat as “The outlaws fill the mountain caves” (609). On the Roman level this seems to describe the gathering of Germanic hordes north of the Alps, as well as civil unrest during and following the period of the Barracks Emperors. But for Auden, this picture is not only the ever-ominous threat of war during the early to mid 20th century, but is also a description of the internal war that he saw being waged within society. This idea carries support from other works, and in fact connects quite closely with a poem that is placed directly before “The Fall of Rome” in Edward Mendelson’s compilation of Auden (Knox 22). This poem is titled “Under Which Lyre,” and it describes the societal reinstatement of the conscripts from World War II, and shows a strange period of reconnecting with normal procedures and daily tasks. One Weathersby 3 stanza in particular stands out in connection with the internal strife in society following the war that connects to the image of “outlaws fill the mountain caves”: Let Ares doze, that other war Is instantly declared once more ’Twixt those who follow Precocious Hermes all the way And those who without qualms obey Pompous Apollo. (Auden “Under” ll. 32-37) Auden seems here to describe not an anxiety over foreign threats, but instead a new battle that forms in society between the progressive intellectuals: “Precocious Hermes” who is both constantly moving towards his destination and is intellectually precocious, and “those who without qualms obey / Pompous Apollo,” or those who have been gifted but seem nonetheless to pursue their own vanities. This pursuit of vanity, as opposed to a sort of intellectual humility, is one of the major points of criticism for Auden in “The Fall of Rome.” In the second stanza, he creates a stark contrast between the images of vanity of the Roman citizenry, and the corrupt nature of the government organizations. In the first line he says, “Fantastic grow the evening gowns” (Ricks 609). This stands out and seems awkward in the stanza which goes on to describe: “Agents of the Fisc pursue / Absconding tax-defaulters through / The sewers of provincial towns” (609). Auden uses juxtaposition in the first line to compare this image with the rest of the stanza to point out the absurdity of the vain obsession with personal appearance, even while society crumbles all around. Auden uses the second description to illustrate the government’s use of relatively menial tasks to avoid confronting major social issues. While Rome is in steep decline, the “Agents of the Fisc” are occupied pursing the tax-defaulters through “the sewers.” His language serves to reinforce the menial nature of the governmental pursuit, which makes a priority out of the Weathersby 4 relatively unimportant back-alley issues, as depicted in his description of “The sewers of provincial towns.” This particular criticism seems almost universally consistent of overwhelmed governments, and was certainly relevant throughout the middle of the 20th century, when the entire world was focused on a war that was never fought. This issue certainly stains against the egocentric concerns of the citizenry of the first line that seem terribly narcissistic after the stanza is through. Auden contrasts these two not only with language, but also with punctuation. Of the two marks of punctuation in the stanza—one of which is a period that marks the end, the first is a semi-colon after the description of “the evening gowns.” Auden chooses this place for punctuation to separate the two images and further isolate the first line. This isolation creates a remarkably distinct contrast. Auden goes on to develop this criticism of societal vanity and governmental backwardness two stanzas later in a description that uses the same contrast of images between the first line and the rest of the stanza. This criticism is another that carries disdain towards the ruling bodies. Throughout his work, Auden seems generally displeased with the conduct of the heads of state in contemporary society as illustrated by this passage from “The Managers”: “…Can They so much as manage To behave like genuine Caesars when alone Or drinking with cronies, To let their hair down and be frank about The world? It is doubtful.”(Auden Selected 124) This attack on “Caesars” manifests itself in “The Fall of Rome,” as well. In fact, Auden uses the same image of the Caesar as a representation for the heads of the government in his inner-stanza juxtaposition as an illustration of corruption. The stanza Weathersby 5 begins with the line, “Caesar’s double-bed is warm.” Auden uses this line to criticize the hypocrisy of the government that is seemingly comfortable, even sleeping, much like the wearers of “the evening gowns,” amongst serious societal struggles. One such issue is embodied in the rest of the stanza “As an unimportant clerk / Writes I DO NOT LIKE MY WORK / On a pink official form” (Ricks 609). Following his critique of the ignorant government, he shows one of the results. In Auden’s poem, unengaged leaders lead to an unengaged body of citizens, like the clerk who “writes I DO NOT LIKE MY WORK.” It is through his poetic wording and use of powerful literary techniques in works like “The Fall of Rome” that Auden reveals his progressive intellectual side in its truest form. Auden is a poet who possesses not only the ability to articulate concepts and controversies, but he is also a poet who is able to convey his intellectual conviction in a beautiful and passionate way. When Auden has a criticism, he exhibits it as a theme in his poetry, and his poetic ability allows him to criticize openly and powerfully. Yet Auden still does not seem a distant prophetic critic of society, but will often engage closely on a sentimental level with the world around him as exemplified by his works like “Musee des Beaux Arts” (3) and “The Unknown Citizen” (Auden Collected 142). This makes Auden particularly admirable as a poet who not only possessed extraordinary poetic skill and intellect, but felt human and a member of the society that he sought to better. Works Cited Auden, W. H., ed. Selected Poetry of W.H. Auden: Second Edition. New York: Random House, Inc., 1971. Weathersby 6 Auden, W. H., ed. The Collected Poetry of W.H. Auden. Kingsport, TN: Kingsport Press, Inc., 1961 Auden, W. H.. “Under Which Lyre.” 20 Nov. 2008. <www.cs.rice.edu/~ ssiyer/minstrels/poems/1082.html Knox, Bernard. “W. H. Auden.” Grand Street 1 (Winter 1982): 18-27. JSTOR. Carlyle Fraser Lib. 17 Nov. 2008. Ricks, Christopher B., ed. The Oxford Book of English Verse. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. Weathersby 7 Most Commonly Annotated Works 1) “Musee de Beaux Arts” 2) “Epitaph on a Tyrant” 3) “Funeral Blues” 4) “The Shield of Achilles” 5) “Lullaby” 6) “In Memory of W.B. Yeats” 7) “The Unknown Citizen” 8) “The Letter” 9) “September 1st, 1939” 10 “Autumn Song”