Ego-Social Identity Profiles during Emerging Adulthood by Melinda

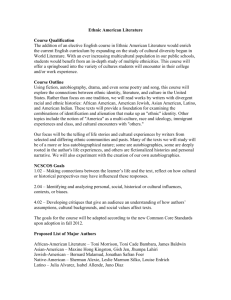

advertisement