Exhuming Hesiod - The Geneva School

advertisement

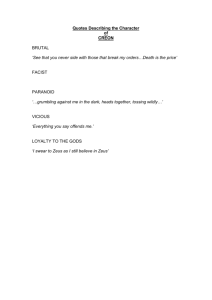

January 13, 2012 Exhuming Hesiod Nick DeGroot 5th Grade Latin; Latin II, V, AP It is generally true that once something is buried, the task of recovery is most difficult, particularly if one has forgotten where to look. Regardless of whether the buried item was once great or insignificant, physical or even intangible, the obscuring effect of burial works equally well in all cases. When once something has been buried and its location forgotten, insight as to its location is, perhaps, the first hope of recovering the lost item. What follows may offer a bit of insight into the nature and location of something great that we have long lost to time’s interring sands. The Greek poet Hesiod is not a household name, and for the last two centuries he has fallen out of vogue and taken as his primary residence the libraries and classrooms of classics departments within the academy. The academy is not to blame for this, I think, for Hesiod has always stood in the shadow of Homer, his more popular contemporary and fellow epic poet. That is not to say that Hesiod has always struggled for popularity, however, for this late-eighth-century B.C. poet from Boeotia (pronounced “bee-oh-sha”, the region of Greece to the northwest of Athens) was intensely popular in classical Athens (i.e., the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.) and the Hellenistic world (i.e., Italy, Greece, Asia Minor, the Levant, and North Africa, ca. 323–31 B.C.), and his influence on some of the more popular figures of antiquity was profound. Plato, if we take him seriously in Books Two and Three of the Republic, would have him banned from his ideal state. Vergil, on the other hand, the greatest poet of the Latin language and, arguably, of the western world, drew inspiration from Hesiod in the writing of his Georgics and (to some degree) the Aeneid. Of the several extant works attributed to Hesiod, scholars generally recognize two as genuine: the Theogony and the Works and Days. While we do not have exact dates for the writing of these poems, we would probably not be far off by placing them between 750 and 700 B.C.; and this puts them right at the beginning of the western literary tradition. They are relatively short epic poems that deal, respectively, with the rise of the gods—Zeus in particular—to supremacy over the world as it currently exists, and how best to live in such a world. The Theogony, which is Greek for “the origin of the gods,” is as systematic an account as we shall get from antiquity of whence the gods came, whom they loved, and how they fought. From it we inherit such stories as the original “clash of the Titans,” i.e., their unsuccessful war with the Olympian gods; the myth of Pandora (though she’s not so named until her appearance in the Works and Days); and the story of Prometheus the fire-bringer, his mountainside bondage, and his being tortured by the daily devouring of his liver by Zeus’ eagle. The Works and Days, as its title implies, takes as its ostensible theme “work” (viz., agriculture, the primary occupation of the pre-modern world) and the calendar, especially as it relates to farming. From it we inherit an elaboration on the stories of Prometheus and Pandora, our concept of a “golden age,” and the source of the stereotypical caricature of the (ancient) Greeks’ misogynistic, curmudgeonly outlook on life. But it would be a shame if this were all we understand of Hesiod. For if we regard the Theogony as a mere genealogy of the gods and the Works and Days as the first farmers’ almanac of the West, we will never truly get to know our “fathers” (i.e., both Hesiod himself and all those Greeks and Romans over whom he exerted such formative influence), and we shall fail to lay hold of the full inheritance of beauty and wisdom bequeathed to us by this particular “father” of ours. In order to dive deeper into our understanding of Hesiod (and, consequently, of all those who have adopted his—and Homer’s—gods), the most convenient approach may be through the Works and Days. We would do well to remind ourselves at the outset that though the Greeks had no scriptures as we have, their poets (who often invoked the inspiration of the Muse[s]) served them in many of the same religious, ethical, and cultural capacities. We may be surprised, then, to discover in this pagan poet rather clear echoes of the Wisdom Literature of the Old Testament (among other writings of the ancient Near East). For example, a significant theme of the Works and Days is the hardness of the human condition and the subsequent need for hard work and dutiful conduct toward the gods; and this sounds not too dissimilar from what we find in the books of, say, Ecclesiastes and Proverbs. An even more illuminating parallel between Hesiod and the Old Testament lies in the supposed source of justice, or “that which is right.” “Right” (dikē in Greek), according to Hesiod, is a goddess and a daughter of the king of the gods, Zeus himself. Notwithstanding some of the aspects of Zeus’ character which might have made him difficult for Plato (among others) and repugnant to a good many Christians from antiquity through today, it is Zeus nevertheless who orders “right,” and it is he who protects her. Human ability to discern “right” derives from Zeus, and he rewards those who honor her and punishes those who harm her: Lay these things to heart and hearken unto Right; forget altogether violent force. For this was the custom which Kronos’ son [Zeus] laid down for humans: whereas fish, beasts, and flying birds of prey devour one another—since Right is not among them—to humans he has given Right, which is by far the best. For if a man should be willing to declare among the people what things he knows to be right, to him wideseeing Zeus would give prosperity; but he who lies, willingly perjuring himself in his witness, therein violating Right, he is blighted beyond cure: his line will drop off rather obscurely thereafter. Yet the line of a man of good witness will thereafter be the better. (Works and Days, 274-85) By no means am I suggesting that Hesiod is a latent Jew or proto-Christian; he is very much a Greek, and his poems reflect a characteristically Greek view of life. He is, however, human, and he is one of the earliest fathers of our tradition. Furthermore, our tradition is comprised of humans, humans who developed wonderful and terrible ideas, to be sure, but humans nonetheless. If we get to know those humans who comprise our tradition—however far up the family tree they may be— we might be surprised to find how fundamental to their experience has been the question of what it means to be human. Indeed, each branch of our tradition (viz., western and Judeo-Christian) has long been asking that question, and nearly as often it finds the answer rooted in the living of life according to “right,” which itself derives from that god whom the tradition deems supreme. Let us, therefore, as heirs of this wisdom handed down by our fathers, work with might and main to prevent our rich inheritance from becoming buried.