WHO TOOK MY IP--DEFENDING THE AVAILABILITY OF

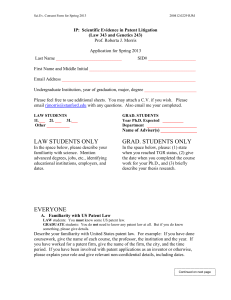

advertisement