HowEvaluateArteryBruit

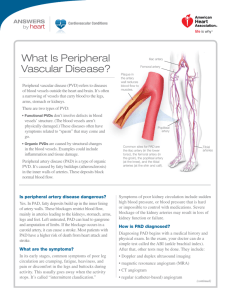

advertisement

CLINICAL INQUIRIES How should you evaluate an asymptomatic patient with a femoral or iliac artery bruit? Evidence-based answer ❚ Additional vascular diagnostic evaluation is not indicated, because no evidence suggests that proceeding with limb revascularization will improve outcomes in limb pain or function (SOR: C, expert opinion). Not enough evidence exists to recommend routine screening for iliac and femoral arterial bruits. Evidence summary modest predictor of disease (LR=2.2, no CI provided).4 One study of 78 patients showed that a femoral or iliac artery bruit accompanied by either thigh claudication or an abnormal femoral pulse predicted PAD. Patients with 2 out of 3 of these clinical findings had an 83% incidence of aortoiliac disease; the incidence was 100% in patients with all 3 findings.5 Another study showed that bruits between the epigastrium and popliteal fossa were found in 63% of 309 patients with arterial disease, but only 7% of 149 patients without PAD diagnosed by AAI or angiogram.6 Femoral artery bruit is better predictor of PAD Further evaluation of an incidental iliac or femoral artery bruit helps assess the patient’s risk of arterial disease. Auscultation of the femoral arteries for a bruit in asymptomatic patients is a moderately good predictor of PAD (likelihood ratio [LR]=4.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.40-9.50). The absence of a bruit doesn’t exclude disease, however (LR=0.83; 95% CI, 0.73-0.95).3 Auscultation of an iliac artery bruit is a more www.jfponline.com 217_JFP0409 217 Katherine M. Walker, MD, CAQSM Brent H. Messick, MD, MS UNC Chapel Hill School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine, and Cabarrus Family Medicine Residency Program, Concord, NC Leonora Kaufman, MLIS Perform an ankle-arm index (AAI, or ankle-brachial index) test to evaluate for peripheral artery disease (PAD) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, cohort studies). If the test detects PAD, recommend steps to modify cardiovascular risk factors (SOR: B, extrapolation from randomized clinical trials [RCTs]). PAD affects 7 million to 13 million Americans, or 3% to 18% of the population. Major risk factors include smoking, older age, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, obesity, cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, hyperhomocysteinemia, and elevated C-reactive protein.1 PAD may cause claudication, ulcers, impotence, or leg or thigh pain, although 20% to 50% of patients are asymptomatic.2 Evidence Based Answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network UNC Chapel Hill, Department of Family Medicine, Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, NC FAST TRACK A femoral or iliac artery bruit in an asymptomatic patient warrants evaluation for peripheral artery disease with the ankle-arm index test. Follow up a bruit with AAI testing Patients with femoral or iliac artery bruits should undergo AAI testing to assess the severity of disease. The AAI has 95% sensitivity and almost 100% specificity in identifying PAD, compared with angiography.3 An AAI >0.90 is considered normal. An AAI of 0.71 to 0.90 indicates mild dis- VOL 58, NO 4 / APRIL 2009 217 3/18/09 11:08:25 AM CLINICAL INQUIRIES ease, 0.41 to 0.70 indicates moderate disease, and ≤0.40 indicates severe disease. Manage risk factors aggressively Although no studies show specifically that modifying risk factors in a patient with asymptomatic PAD affects long-term outcomes, aggressive risk factor management is recommended because PAD is highly associated with cerebrovascular and coronary artery disease.1 No data suggest that treating asymptomatic PAD improves future limb pain or function. Recommendations The American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association 2005 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease2 make the following recommendations for patients with asymptomatic lower extremity PAD: • Identify patients with asymptomatic lower extremity PAD by examination or by measuring the ankle-brachial index so therapeutic interventions known to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, and death can be offered (level of evidence [LOE]: B). • Address smoking cessation, lipid lowering, and diabetes and hypertension treatment according to national guidelines (LOE: B). • Consider antiplatelet therapy to reduce the risk of adverse cardiovascular ischemic events (LOE: C). The United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends against routine screening for PAD (D recommendation).7 ■ Acknowledgments Special thanks to Felipe Navarro, MD. References 1. Peripheral Arterial Occlusive Disease. Fpnotebook [database online]. Available at: http://fpnotebook. com/SUR3.htm. Accessed January 8, 2008. 2. Hirsch AT, Hazkal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1239-1312. 3. Khan N, Rahim SA, Anand SS, et al. Does the clinical examination predict lower extremity peripheral arterial disease? JAMA. 2006;295:536-546. 4. McGee SR, Boyko EJ. Physical examination and chronic lower-extremity ischemia: a critical review. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1357-1364. 5. Johnston, KW, Demorais D, Colapinto RF. Difficulty in assessing the severity of aorto-iliac disease by clinical and arteriographic methods. Angiology. 1981;32:609-614. 6. Carter SA. Arterial auscultation in peripheral vascular disease. JAMA. 1981;246:1682-1686. 7. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for peripheral arterial disease. August 2005. Available at: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstf/uspspard.htm. Accessed February 27, 2009. FACULTY READ ABOUT BIPOLAR SPECTRUM DISORDERS AND EARN 2.5 FREE CME CREDITS D O N ’ T M I S S T H I S 12 - PAG E C M E S U P P L E M E N T HENRY A. NASRALLAH, MD, PROGRAM CHAIR Professor of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Neuroscience University of Cincinnati College of Medicine Cincinnati, Ohio DONALD W. BLACK, MD FREE Professor of Psychiatry University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine Iowa City, Iowa 2.5 CME CREDITS JOSEPH F. GOLDBERG, MD Associate Clinical Professor of Psychiatry Mt Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York Silver Hill Hospital, New Canaan, Connecticut DAVID J. MUZINA, MD Vice Chair for Research & Education Associate Professor of Medicine Cleveland Clinic Department of Psychiatry & Psychology Cleveland, Ohio STEPHEN F. PARISER, MD Professor of Psychiatry, Obstetrics and Gynecology Medical Director, Psychiatry Clinics Medical Director, Neuropsychiatry Ohio State University College of Medicine Columbus, Ohio Recognizing and managing psychotic and mood disorders in primary care RELEASE DATE: DECEMBER 1, 2008 EXPIRATION DATE: DECEMBER 1, 2009 INTRODUCTION › HENRY A. NASRALLAH, MD LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reviewing this material, clinicians should be better able to: • Achieve early and accurate diagnosis of patients with mood disorders • Utilize available screening tools effectively • Understand the mechanisms of action, hepatic effects, and other metabolic effects of available agents and their potential impact on treatment • Develop an effective treatment plan that includes monotherapy or combination therapy • Select the most appropriate agent(s) for short- and long-term treatment to meet individual patient needs TARGET AUDIENCE Psychiatrists, primary care physicians, and other health care professionals who treat patients with psychotic and mood disorders CME ACCREDITATION STATEMENT The University of Cincinnati designates this educational activity for a maximum of 2.5 AMA PRA Category 1 credits™. Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. This CME activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the sponsorship of the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. The University of Cincinnati College of Medicine is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians. FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES AND CONFLICTS OF INTEREST According to the disclosure policy of the University of Cincinnati, faculty, editors, managers, and other individuals who are in a position to control content are required to disclose any relevant financial relationships with the commercial companies related to this activity. All relevant relationships that are identified are reviewed for potential conflicts of interest. If a conflict of interest is identified, it is the responsibility of the University of Cincinnati to initiate a mechanism to resolve the conflict(s). The existence of these interests or relationships is not viewed as implying bias or decreasing the value of the presentation. All educational materials are reviewed for fair balance, scientific objectivity of studies reported, and levels of evidence. THE FACULTY HAS REPORTED THE FOLLOWING: DR NASRALLAH reports that he is on the advisory board of Abbott, AstraZeneca, Cephalon, Janssen, Pfizer, and Vanda Pharmaceuticals; is a consultant for AstraZeneca, Janssen, Pfizer, and Vanda Pharmaceuticals; receives grants from AstraZeneca, Forest Laboratories, Janssen, Otsuka America Pharmaceutical Inc., Pfizer, Roche, and sanofi-aventis; and is on the speakers bureau of AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Pfizer. DR BLACK reports that he is a consultant for Forest Laboratories and Jazz Pharmaceuticals and receives grant(s) from Forest Laboratories. DR GOLDBERG reports that he is on the advisory board, speakers bureau, and serves as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly & Co, and Glaxo SmithKline. DR PARISER reports that he receives grants from Pfizer and is on the speakers bureau for AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer. DR MUZINA reports that he is on the advisory board of AstraZeneca and Bristol-Myers Squibb; and is on the speakers bureau of AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Sepracor, and Wyeth. PLANNING COMMITTEE: Kay Weigand, University of Cincinnati; and Kristen Georgi, Charles Williams, and Katherine Wandersee for Dowden Health Media have disclosed no relevant financial relationship(s) with any commercial interests. No off-label use of drugs or devices are discussed in this supplement. SUPPORT Supported by an educational grant from AstraZeneca. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This CME activity was developed through the joint sponsorship of the University of Cincinnati and Dowden Health Media. It was edited and peer reviewed by The Journal of Family Practice. T he diagnosis and management of psychotic and mood disorders is an evolving process and an important clinical topic for primary care clinicians (PCPs). Although many reports exist on the prevalence and treatment of depression in primary care, far less information is available about patients in this setting with depression accompanied by symptoms of mania or hypomania.1 To facilitate a dialogue on the identification and treatment of psychotic and mood disorders, we invited 4 expert faculty members to present actual patient cases followed by a panel discussion in which the collective experience of all the faculty lends further practical insights into the nuances of management of such patients in both inpatient and outpatient settings. In particular, these cases underscore the importance of being alert to critical clues in a patient’s history or the family’s history. A larger version of this panel discussion appears in a supplement to the December 2008 issue of CURRENT PSYCHIATRY. We’ve extracted the portion that we felt would be of most interest to primary care providers. The case selected for presentation here is by David Muzina, MD, and concerns a 20-year-old man who was referred for psychiatric evaluation by his PCP and psychologist for treatment of mood swings, anxiety, and confusion. He had been given sertraline and then venlafaxine, but discontinued both medications on his own. His symptoms began rather abruptly 14 months earlier, coinciding with an intense program of weight lifting and supplement use to change his self-described smallness. Profound, persistent sadness and feeling “dead inside” were his chief complaints, and they had led to a break-up with his girlfriend, which distressed him greatly and preoccupied his thinking. He also believed his parents were hiding from him the truth of a significant birth defect. Following the case presentation is a faculty discussion of several pivotal issues in the management of mood disorders: • Pitfalls to avoid during the diagnostic evaluation • Pros and cons of monotherapy and combination therapy • Mechanisms of action of available medications and implications for an effective treatment plan • Suggestions for enabling patient compliance with prescribed regimens We hope the insights you glean from this exchange of practical clinical issues will enhance and confirm your own approach to diagnosing and treating patients with psychotic and mood disorders. REFERENCE © 2008 AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRISTS AND DOWDEN HEALTH MEDIA jfponline.com and currentclinicalpractice.com 1. Das AK, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in a primary care practice. JAMA. 2005;293:956-963. Supplement to The Journal of Family Practice ❙ Vol 57, No 12s ❙ December 2008 S5 AVAILABLE ONLINE AT JFPONLINE.COM Recognizing and managing psychotic and mood disorders in primary care Read a case referred to psychiatry by primary care and find out how experts manage the care of patients with psychotic and mood disorders. FAC U LT Y } HENRY A. NASRALLAH, MD, PROGRAM CHAIR } DONALD W. BLACK, MD } JOSEPH F. GOLDBERG, MD } DAVID J. MUZINA, MD } STEPHEN F. PARISER, MD THIS CME ACTIVITY IS SUPPORTED BY AN EDUCATIONAL GRANT FROM ASTRAZENECA AND DEVELOPED 218 218_JFP0409 218 THE JOINT SPONSORSHIP OF THEPRACTICE UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI AND DOWDEN HEALTH MEDIA. VOL 58, NO THROUGH 4 / APRIL 2009 THE JOURNAL OF FAMILY 3/18/09 11:08:29 AM