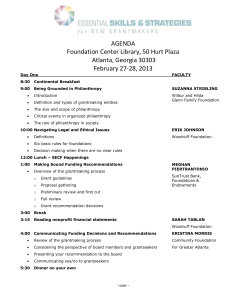

Confronting Systemic Inequity In Education: High Impact Strategies

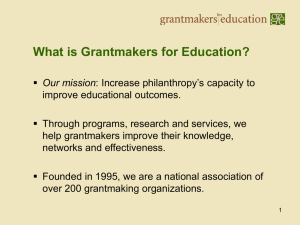

advertisement