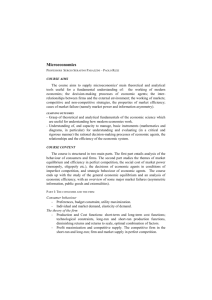

Microeconomics Reading Assignments: Under the heading, Lecture

advertisement

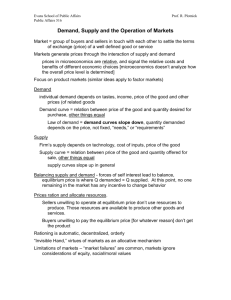

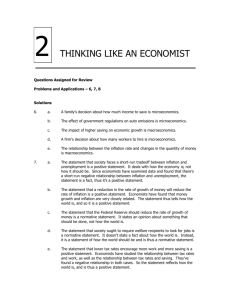

Microeconomics Reading Assignments: Under the heading, Lecture Schedule, I have assigned one chapter or two for you to read each session. Ideally, you may want to read it once before the lecture. It will be somewhat easier for you to understand the lecture that is being covered. A second reading should be done after the lecture. Examinations: Two exams plus the final examination, equally weighted. Also, a case report on a specific economic problem in Hong Kong. Each student is asked to prepare a report on it. Length: 10 – 20 pages. Bonus Points: 1. Every once in a while, I may ask you some bonus questions. If you answer it correctly, you receive a bonus point. Each bonus point is worth 1% of total score. 2. If I make a mistake and you correct it, you would get a bonus point (which applies to only important points). Introduction In the beginning, economics was not diversified, and all economic topics were lumped together and called "economics." After the great depression of the 1930s, there emerged two branches of economics: microeconomics and macroeconomics. Most of the time, a manager’s decisions deal with microeconomic decisions of a firm, although some managers have to pay attention to macroeconomic indicators such as interest rates and exchange rates. Micro comes from the Greek word (micros = small), "Macro" means large. Ragnar Frisch (1895-1973), a Norwegian economist (who along with the Dutch economist, Jan Tibergen, won the first Nobel prize in economics) coined the words "microdynamics" and "macrodynamics" in 1933, to denote what we now mean by micro and macroeconomics. Two main differences: 1. Microeconomics deals with the choice of individuals, individual households or individual firms. Macroeconomics deals with economic aggregates, total production, total consumption, etc. Even in microeconomics, sometimes we also use aggregate concept such as aggregate demand for a product. Still, we are focusing on a single product in microeconomics. In macroeconomics, we talk of GNP, which is an aggregate over many different products. 2. In microeconomics, relative prices play an important role. In macroeconomics, we pay attention to general price level, interest rates, etc., but not to individual prices or markets for specific products. SCARCITY AND CHOICE Individuals make choices: • whether to get an MBA or not • whether to buy a house or rent • whether to buy a car or use bus or train • whether to marry or stay single. 2 Some are non-economic choices moral decisions religious decisions Economic decisions some are purely economic decisions others are moral or religious decisions that have some economic consequences. If moral decisions are made, regardless of economic consequences, those decisions can be truly noneconomic decisions. It is difficult to find any decisions that are totally independent of economic consequences. ⇒ most decisions yield economic consequences, or are affected by economic events. Any decisions, political, religious or social, that use up resources have economic consequences. When economic consequences are taken into account, moral and social decisions are not purely moral or social decisions. Few people can make purely political or religious decisions without taking into account the economic costs or consequences of such actions. There may be tradeoffs between moral/social and economic activities. Societies often do not tolerate tradeoffs ⇒ Lexicographic preferences (no tradeoffs). Throughout the semester, we will be concerned only with economic decisions of economic agents. This does not mean that managers should ignore moral and social consequences of economic decisions. However, such consequences will be ignored in this course, as it is beyond the scope of economic analyses. Example: Managers are supposed to maximize profits. There may be legal means Illegal means Illegal means often yield a higher level of profits than legal means. Hence, the former method is often subject to criticism and prosecution. Drug lords/Mafia/Triad: engage in illegal activities. (Some actions are legal in one country but may be illegal in another.) 3 Similarly, producers also have a number of choices: • • • • • what product to produce whether to expand output whether to shut down a plant whether to buy inputs from abroad whether to produce abroad POSITIVE VS NORMATIVE ANALYSIS (vs. = versus) It is common knowledge that economists often agree. These differences result from different assumptions or hypotheses about how things are or from different views about how things ought to be. different opinions about what is (facts) different opinions about what ought to be (value judgment) Positive economics deals with the question of what is: • Positive statements deal with assumptions about the state of the world and some conclusions. • The validity of a positive statement can be verified in principle, no matter how difficult it might be. Example 1: The weight of the earth is 6 septillion (6x 1024) kilograms. Example: An increase in minimum wage increases unemployment among teenagers. Positive statements do not involve value judgments or opinions. These are normative statements. • Verifying the validity of a positive statement is often difficult in practice. "If the price of a good declines, consumers will buy more of that product." The verifying process often requires some judgment as regards to the specific method to be adopted to verify a claim. To verify this, one has to observe the consumption pattern over a period. How long should one observe the consumer? (normative) 4 Tracking the same consumer is impractical. Consumers do not cooperate long enough to permit your experiment or observations. How large the sample should be to confirm the result? (normative) Should one observe all consumers? Observing all consumers is impossible. Men are mortal (can't observe all) Researchers can observe only a sample, a small fraction of the entire population. How big should the sample be? 0.0001%, 1%, 99%, or 100%? To verify a positive statement, one has to be content with a small sample. Some individuals use a single sample. "I will never make the same mistake" or “I will never date another man (or woman).” Those who keep making the same mistake believe that their samples are too small. The same move may eventually produce a different result. Why Assumptions? Verifying the validity of a positive statement is not simple. It actually involves making some assumptions about the statement of the world. So economists lump all these things that they do not want to verify into a set of assumptions, and start from there. It is just too costly to verify the reality or validity of the assumptions. For instance, we will assume that consumers are "rational", i.e., consumers should maximize utility. Producers are rational, and hence they should maximize profits, etc. With these assumptions, we try to prove or predict the behavior of consumers or producers. Remark: 1. Real world problems are much more complicated than those we study in this course. For instance, there are many irrational people out there. Or most of the rational people are sometimes irrational. A certain behavior may appear to be irrational, but it may be rational in a broader framework. That is, there may be a good reason for an apparently irrational behavior. 5 2. Many economic decisions are solely based on economic factors, but are partly affected by noneconomic factors. (Similarly, some noneconomic decisions may be partly influenced by economic factors). In this course, we are mostly concerned with economic reasoning: (i) It is difficult to predict the behavior of irrational individuals. (ii) The fraction of irrational individuals is small and their decisions do not alter the overall pattern of consumer behavior. Normative economics deal with the question of what ought to be or value judgment. 6 Practice 1. A cut in wages will reduce the number of people who are willing to work. 2. High interest rates prohibit many young people from buying their first home. 3. The government should reduce the number of minority members in the military and increase the number of whites. 4. The government ought to supply a medical insurance scheme for everyone free of charge. 5. The government ought to behave in such a way as to ensure that resources are used efficiently. 6. Hong Kong government should increase its budget allocation to reduce the number of illegal immigrants from China. COMPARATIVE STATICS AND DYNAMICS Equilibrium is a state of balance between opposing influences. Comparative statics compares equilibrium positions when external conditions change. Here we concentrate only equilibrium positions. We are not concerned with how long it takes to achieve the equilibrium positions or by what channel or path the equilibrium is achieved. Dynamics is concerned with whether an economic system in disequilibrium reaches an equilibrium position, how long it takes, and which path it follows to do this. SHORT RUN AND LONG RUN ANALYSIS A short run is a time period during which consumers and producers have not had enough time to make all the adjustments to the new situation. A long run is a time period during which consumers and producers have had enough time to make all the adjustments to the new situation. 7 Consider a sudden increase in the oil price by OPEC. The immediate impact: a sudden increase in the prices of refined oil and other products that use oil. After a while, consumers switch to fuel-efficient automobiles and appliances. These adjustments reduce demand for oil, and lower the oil price. How short is a short run and how long is a long run? This is a difficult question to answer. It depends on the problem in question. In the case of oil price increase by OPEC in 1973, Milton Friedman predicted a decline in oil prices shortly thereafter. However, oil prices rose continuously through the 1970s, and began to decline only in 1980. GM and Chrysler Corporations thought that the oil price increase was temporary and resisted a move to manufacture fuel-efficient cars. As a result, American auto manufacturers lost a sizeable share to Japanese manufacturers. 8 PARTIAL AND GENERAL EQUILIBRIUM ANALYSIS Partial equilibrium analysis uses the ceteris paribus assumption. This is a Latin phrase which means "other things being equal." In practice, other things are never "equal" or remain the same. However, if the changes in the other things are small, the ceteris paribus is a reasonable approximation. Partial equilibrium analyses are used in two situations: 1. The first case is when we are interested in an event that affects only one industry. An example is a labor strike which occurs only in one industry with the impact on other industries almost negligible. 2. The second case is when we are concerned with first order effects, i.e., the impact of an event only on one industry. The event may have impacts on other industries, but these impacts may be outside the scope of the analysis or interests. For instance, we may want to analyze the impact of an automobile import quota. The primary effect is felt in the automobile industry. The auto industry may ask an economist to study the impact on quota on automobile prices. Obviously, such an import quota will have an impact on the steel industry, the aluminum industry, the glass manufacturing industry, the upholstery industry, etc. These effects are secondary or tertiary. Partial equilibrium analysis was popularized by the English economist, Alfred Marshall. (1842-1924) Most of the time, we use this approach. This approach permits graphical analyses. General Equilibrium analysis is concerned with the effects of a change (in policy variable or exogenous conditions) after all sectors have made adjustment to the new situation. For instance, the import quota on automobiles will have impacts on gasoline, steel, aluminum, glass, platinum, and other industries, and these in turn will have further impacts on the auto industry. Models Economic analysis begins with models. What is a model? It is simply a description of the economist's view of how the economy works. 9 Economists generally build simple models and then gradually complicate them. Why? The modeler or the analyst has a finite mind, and cannot capture the total reality. He always looks at the real world from an angle. The above picture shows wine production in a California winery. It has too many details. While the picture may accurately describe the production activity of a vineyard, it has too many unnecessary details that are not relevant to an analysis at hand. Instead of an accurate picture or snap shot of many buyers (men and women) that might be interested in buying a product, N identical consumers may be used to describe a market. Often we talk of the representative consumer with no description of its gender. (In reality, there may not exist any consumer who looks like the representative consumer, who is neither male nor female.) 10 (crowd on the eve of pallio, Siena, Italy) Also, a typical consumer buys thousands of different products each year. However, the model is interested in a particular market. Instead of describing individuals who consume thousands of goods, we often single out one or two goods and then lump all other goods together. For example, if we are interested in analyzing consumer choice between Genetically Modified products, and genetically modified organism (GMO)-free products, we may assume the individual consumes X (the product being investigated) and Y (GMO-free goods) and Z (all other goods), instead of listing thousands upon thousands of goods. 11 The model must contain some essential aspects of the real world that need to be analyzed. What are essential depends on the problem, i.e., they depend on the purpose of the desired economic analysis. However, since the real world is complicated, the economist's task of constructing a simple model is not very simple. In constructing a simple model, the economist has to make some "simplifying" assumptions. Examples: No uncertainty All consumers have the same tastes One or two goods. None of these assumptions are realistic. However, some aspects of reality are irrelevant or negligible for the problem to be analyzed. Some "unrealistic assumptions" are justified on the ground that they enable us to concentrate on the essential aspects of the problems while ignoring irrelevant details. A model is a simplified sketch of the real world. Economists favor simple models because they are easier to understand, communicate and test with data. There are two common criticisms: (i) The model is oversimplified. (2) Assumptions are unrealistic. 12 Remark 1: It is better to start with a simplified model, make sure that it is working and predicts something, and then progressively complicate it. Remark 2: Milton Friedman To be important, a hypothesis must be descriptively false in its assumptions. Choosing CEOs/Leaders Western Method: First, choose MBAs/Drs from top business schools. Then recycle them among the business firms. Problem: The rich and well-educated do not understand the middle class. The current financial mess is the result of the inability of policy makers to understand the middle class and the poor. Paul Volcker: 1979-1987 (during the Great Inflation era, 1980-1984, Carter era). Harvard MA. Alan Greenspan: 1987-2006, Fed Chairman, dropped out of Columbia Univ. Eventually received a PhD from NYU in 1977. Ben Bernanke, 2006- , Harvard BA, MIT PhD, 1979. Japan: Choose CEOs internally. They understand every aspect of a firm’s operation, and set wages fairly. 13 14