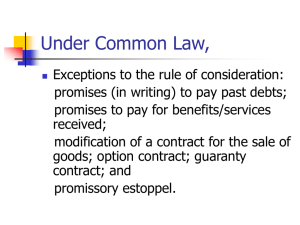

COMMERCIAL TRANSACTIONS UNDER THE

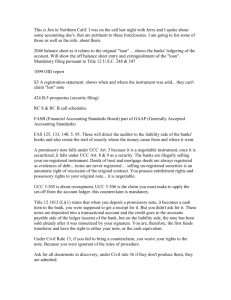

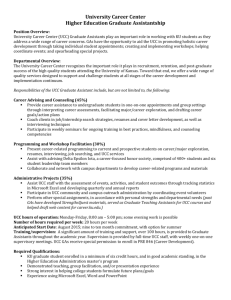

advertisement