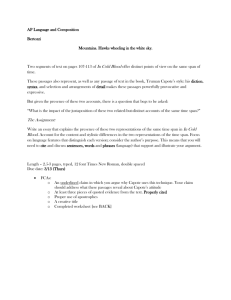

“AS GRACEFULLY AS GREEK TEMPLES”: TRUMAN CAPOTE'S IN

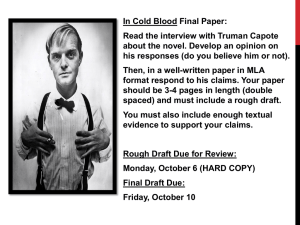

advertisement