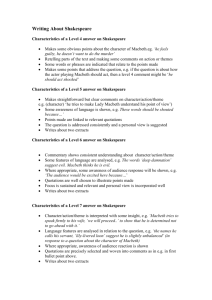

Shakespeare's Greater Greek - Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship

advertisement