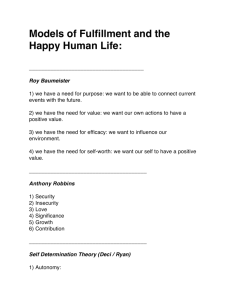

The Role of Need Fulfillment in Relationship Functioning and Well

advertisement