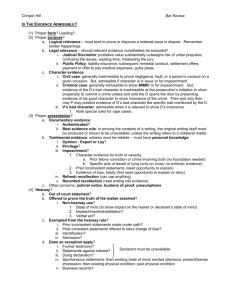

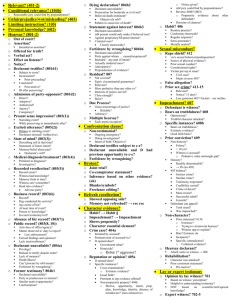

Hearsay - An Exception for Every Objection

advertisement