Guidelines for Care: Person-centred care of people

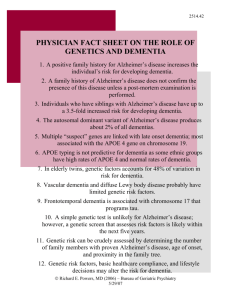

advertisement