Medical treatment - Victorian Law Reform Commission

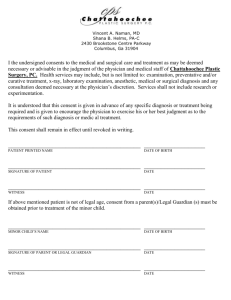

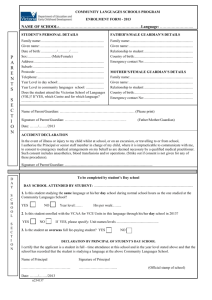

advertisement