German lessons - ToUChstone blog

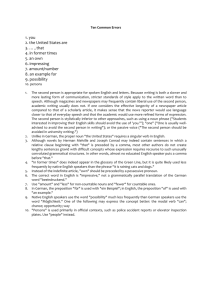

advertisement