12 APPLICATION OF KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT IN THE

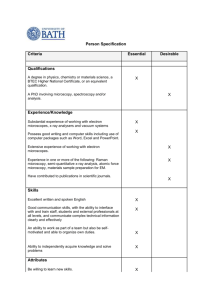

advertisement

APPLICATION OF KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT IN THE MALAYSIAN AIRLINE INDUSTRY: A CRITICAL REVIEW Rain Low Swee Foon and Lum Soo Eurn SEGi University College 9, JalanTeknologi, Taman Sains Selangor, Kota Damansara PJU5, 47810 Petaling Jaya E-mail: rainlow@segi.edu.my ABSTRACT Knowledge has been perceived as the key strategic asset of an organization in the current competitive and unprecedented business environment, particularly in the vulnerable airline industry which has been tremendously affected by the soaring world oil price. As the future success of airlines comes to depend on how quickly and flexibly airlines respond to changes in customer demand, an uncertain business environment as well as competitors’ challenges, greater emphasis needs to be placed on how knowledge management can bring competitive advantage for the organization in the form of superior operational effectiveness and strategic positioning. Knowledge management covers broad and multidimensional aspects like ICT, organizational learning, intellectual capital (human capital, relationship capital and structural capital), organization design (complex knowledge), and e-commerce. The literature review conducted shows that the application of knowledge management in the industry focuses mainly on the four major constructs, namely ICT, organizational learning, intellectual capital and knowledge sharing. The objective of this paper is to analyze the current use of knowledge management in the Malaysian airline industry and to provide a strategy for the future use of knowledge management in the industry. 1.0 INTRODUCTION Knowledge is a shared collection of principles, facts, skills and rules embodied within a firm’s knowledge assets through which competitive advantage is achieved (Stonehouse and Pemberton, 1999). Managing knowledge is a prerequisite for companies operating in today’s hyper-competitive and ever-changing environment whose survival and performance is dependent on their relative speed and ability to develop durable and adaptable knowledge-based competencies (Nonaka, 1991). Knowledge, while difficult to manage, is a strategic organizational asset (Shepard, 2000) and according to Nonaka (1991), is the only lasting source of competitive advantage. Knowledge can be specific or generic to varying degrees (Stonehouse and Pemberton, 1999). Specific knowledge is unique to the firm and as such, is a more likely source of competitive advantage and the basis of core competences compared to generic knowledge which is necessary for operating the business (Stonehouse and Pemberton, 1999). 12 The airline industry with its scale, complexity, highly competitive and volatile nature, and its dependence on knowledge and information as a source of competitive advantage makes an excellent case for demonstrating how Knowledge Management (KM) is used to gain competitive advantage. This study specifically explores the following KM-related aspects in relation to the current and potential use of KM within the Malaysian airline industry. 1.1 Information and Communication Technology (ICT) ICT enables KM by allowing vast amounts of data to be captured, processed, stored and disseminated to the right people at the right time. Internet technology, web-based interfaces, intranets, and portals are key KM infrastructures (Pemberton and Stonehouse, 1999). 1.2 Organizational Learning Organizational learning represents a conscious effort of the organization to develop and is a continuing and continuous process aimed at acquiring skills and knowledge (Pemberton and Stonehouse, 1999). Organizations learn as their individual members learn (Argyris and Schon, 1996) and individual learning is dependent on the organization’s cultural, structure, and infrastructure context in which it takes place; the context can hasten or hamper the learning process (Pemberton and Stonehouse, 1999). 1.3 Intellectual Capital In the competitive business landscape of the 21st century, the new business paradigm of knowledge is power and a knowledge-era global phenomenon has made intellectual capital more crucial than financial capital. Intellectual capital refers to intellectual materials that have been formalized, captured, and leveraged to produce higher-valued assets (Klein and Prusak in Stewart, 1997). It comprises human resources (skills, know-how, competence), stakeholder relationships (customers, suppliers, partners, government), and organizational resources (systems, processes, corporate culture, management style, intellectual property, brands). 1.4 Knowledge Sharing and Culture This process of KM identifies existing and accessible knowledge, in order to transfer and apply such knowledge to solve specific tasks better, faster and cheaper than they would otherwise have been solved (Christensen, 2007). But the willingness to share knowledge is dependent on organizational culture which is embedded within a firm’s structure, stories and spaces (McDermott and O’Dell, 2001). KM-friendly organization culture is a necessity for successful KM implementation. Examples of KM-friendly organization culture are being innovative, trusting, flexible, adaptable, risk taking, performance-oriented, problem solving, team-oriented, with appropriate rewards and incentives, sharing information freely, enthusiasm for the job, tolerant of failure and supportive of superior performance. 13 2.0 INDUSTRY ANALYSIS The Malaysian airline industry is in an oligopoly market structure, where it consists of one full service carrier (FSC) Malaysia Airline System (MAS) and two no-frills carriers, namely AirAsia and Firefly. The Malaysian airline industry is tightly regulated by the government and was dominated by the state-controlled MAS before the government’s domestic liberalization exercise opened up the market to allow AirAsia to join the industry. Following Porter’s (2001) generic competitive strategy, MAS and AirAsia operate on different business models. As a full service carrier (FSC), MAS follows a differentiation strategy and charges a fare premium. In contrast, AirAsia uses a cost leadership strategy. Due to their different strategic positioning, AirAsia and MAS differ in their customer value propositions as well as target market segments. Table 1 provides a summary of the main differentiating characteristics between MAS and AirAsia. Product features Brand AirAsia (LCC) MAS (FSC) One brand: low fare Fares Simplified fare structure, 60-70 percent cheaper than MAS’s fares One product: low fare Small pitch, free seating Brand extensions: fare+service Complex fare: structure+yield management Multiple integrated product Generous pitch, seat assignments Two class (dilution of seating capacity Ticketless, IATA ticket contract Primary Online, direct, travel agent Product Seating Class segmentation One class (high density) Check-in Ticketless Airport Distribution Secondary (mostly) Online and direct booking Point-to-point Connections Customer service Inflight Aircraft utilization Turnaround time Aircraft Ancillary revenue Operational activities Generally underperforms Pay for amenities Very high 25 minutes Single type: commonality Advertising, on-board sales Core (flying), extending to tour operations, financial services, cargo Interlining, code share, global alliances (hub-tospoke) Full service, offers reliability Complementary extras Medium to high: union contracts Low turnaround: congestion/ labor Multiple types: scheduling complexities Focus on the primary product Extensions: e.g. maintenance, cargo 14 Table 1: Product Features of Airasia and MAS (O’Connell and Williams, 2005) In year 2001, AirAsia had successfully stimulated and captured the growth of discretionary air travel traffic by targeting mostly first-time travelers and budget leisure travelers. The business expansion was tremendous and has since captured a significant market share in South East Asian countries. AirAsia is currently the leading domestic carrier with 6.5 million passengers compared to MAS’s 5.4 million. Its low cost strategy and successful positioning strategy in Asian market that has putting it as the market leader in the Asian airline industry. MAS, despite being an award-winning airline, has struggled financially in the past and has only recently completed its business turnaround exercise. Moving on, MAS is embarking on a business transformation to secure its future competitive position. Competition between the two is intensifying as both begin to move into each others’ core markets and engage in price-cutting measures. AirAsia has set up a new franchise airline, AirAsia X to service long-haul routes and as a defensive move MAS has set up its own LCC, Firefly (Thomas, 2007). This, in addition to the airline industry’s turbulent operating conditions, declining yields and increased foreign competition paints a long and difficult road ahead for both airlines. Competitive advantage will have to be gained through operational effectiveness and strategic positioning (Porter, 2001). 3.0 CURRENT USE OF KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT IN THE MALAYSIAN AIRLINE INDUSTRY 3.1 Information Communication Technology The modern airline industry is dependent on ICT for its operations, namely the yield management system (YMS), computer reservation system (CRS), and enterprise resource planning system (ERP). The systems also play a pivotal role in generating and integrating information assets into organizational decision-making and a knowledge building process which helps to improve airlines’ value chains and operational efficiency. YMS helps airlines to maximize revenue for each flight and is instrumental in improving MAS’s previously poor yields. Meanwhile, AirAsia has realized increased revenue (3-4%) for the same number of aircrafts by leveraging on computer forecasted high/ low demand patterns that effectively shift demand from low to high periods and by charging a premium for late bookings (Kho et al., 2005). The CRS helps to fuel AirAsia’s dramatic growth (from 2.2 million to 7 million passengers within 2 years) and minimize costs as a direct sales engine by eliminating commissions paid to travel agents and ticketing and handling costs (AirAsia, 2008). MAS’s e-ticketing is to save it RM 19 per ticket and e-CRM is helping it to manage its frequent flyer loyalty program and utilize customer database more effectively (MAS, 2007). Other KM technologies such as collaboration, mobile work, content management, business intelligence, business process management (BPM), and knowledge sharing are also employed within the industry. MAS’s new Integrated Human Resource Management System has helped it to reduce administration costs, improve data management and increase its HR division’s efficiency (MAS, 2007). See Appendix 1for on how ICT enables connectivity to multiple direct sales channels in the aviation industry. 15 3.2 Organizational Learning MAS and AirAsia are continuously learning to gain knowledge, that when applied, will lead to improved organizational performance. MAS, after its successful business turnaround is learning to internalize the new ways of working whereas AirAsia is learning to cope with its market expansion and cost efficiency. Together, they are learning to cope with the difficult operating conditions faced by many global airline companies. Going further, the organizational learning context consists of three elements; people, processes and technology. Staff is a key aspect of knowledge management as knowledge is developed and controlled by them. According to Ingram and Baum (1997), organizations can learn from their own and their industry’s experience which MAS did with its diverse business committee team. Both airlines use an integrated performance management system to improve staff competency and secure future talent. MAS’s e-learning portal provides it with personalized, timely, current, and user-centric educational activities via consolidated access to learning and training resources from multiple sources. MAS and AirAsia both own training academies as part of their human capital development plans and have made leadership development a priority. KM has helped both airlines to continuously improve their operational effectiveness by setting procedures, standards, performance targets and adopting best practices. Efforts are aimed towards improving the cost structure through more effective yield management and better fuel hedging strategies. AirAsia, with its aim to become the lowest cost airline in every market that it serves is relentless in cutting costs. It has clear policies and guidelines covering all areas of flight operations. Its pilots have managed to lower fuel consumption by 20 % and doubled the landings it gets from the tires (Ricart and Wang, 2005). Technology plays a major role in KM. Pemberton and Stonehouse (1999) assert that only those businesses that keep abreast with technological developments will be able to manage knowledge effectively; resulting in rapid learning and greater intelligence that will lead to the generation and sustenance of competitive advantage. MAS’s internal division facilitated the replacement of its severely inadequate legacy accounting system to result in improved quality and timeliness of information for management decision-making and significant reduction in manpower (MAS, 2007). Technology also forms the basis of airlines’ distribution model. Both airlines are now engaging in a promotional price war via their company websites. AirAsia and MAS have emerged from their respective double-loop (Argyris and Schon, 1978) and generative learning (Senge, 1992) with new ways of doing things and new business opportunities. MAS is using its knowledge from the recently ended business turnaround exercise to improve its future competitiveness. It has set up Firefly, a new budget airline to compete more effectively with AirAsia. Through Firefly, MAS also intends to learn the knowhow of managing a low-cost operation before adopting Firefly’s processes into MAS (MAS, 2007). Meanwhile, AirAsia is generating new competences centered on industry learning by adding financial services, and tour and accommodation to its product offer. It is also expanding into long-haul flight operations through a new franchise airline. 16 3.3 Intellectual Capital Analysis on the intellectual capital in the Malaysian airline industry can be grouped into three different perspectives. They are human resources, stakeholder relationship and organizational resources. In terms of the human resources aspect, AirAsia’s people play a key role in the success of its low-cost business model. AirAsia trains its employees to be innovative multitaskers and team players. AirAsia also stresses internal recruitment and relies on its Human Resources Department for this. Meanwhile, MAS is moving towards greater employee empowerment and involvement and is using web-based talent management solutions to support compliance training, reporting, and performance management across its global workforce. Both airlines have taken steps to protect their intellectual capital in the event of staff turnover by having succession plans for key personnel. Maintaining favorable relationships with stakeholders is paramount for any businesses, especially in the airline industry, where stakeholders yield considerable power. AirAsia’s excellent negotiation and lobbying skills with governments, airport authorities, international partners and suppliers have been critical success factors to the company especially in supporting its business development and planning strategies. AirAsia, indeed started its business by tackling the basic flight passengers’ need, which is low-cost; and offered the routes which were not effectively served competitors. In other words, AirAsia possessed the knowledge capabilities of identifying what customers want, creating profitable routes under-served by other airlines within South-East Asia, as well as efficiently increasing flight frequencies in established and high growth markets. MAS has taken a more proactive approach in engaging its stakeholders (government, partners and suppliers) through a new External Relations Department to help meet its various interests. As a result, MAS has entered into various new code-sharing partnership agreements with other airlines as well as establishing a Suppliers’ Forum for supplier relationship management. Both airlines also actively engage their stakeholders in their performance, issues and plans using a variety of means such as the media and intranet to raise their company profiles and improve communication with employees. AirAsia regards its AirAsia brand as a valuable asset and has been aggressively promoting it using bold branding strategies such as high-profile sports sponsorships (such as Formula One racing and Manchester United Football Club), and charity and community projects to raise brand awareness in both its current operating and non-operating markets. It has also leveraged its powerful brand and branding expertise to diversify into financial services, tour and accommodation. Meanwhile, MAS is using its established premium airline brand to attract and retain more passengers. Both leverage on their respective expertise in training and development (AirAsia) and aircraft maintenance and services (MAS, AirAsia) to perform third party work to generate additional profit streams. MAS’s revenue from third party work grew from RM 100 million in 2005 to RM 300 million in 2007 (MAS, 2007b). 3.4 Knowledge Sharing and Culture Airlines share knowledge with both internal members and external parties such as financial institutions, government, commercial partners, suppliers, and customers to establish a powerful network which they can leverage to their advantage. Through code-sharing and inter-linking 17 with other airlines MAS has established a well-balanced network that covers all of its key markets and this has had a direct positive impact on its bottom line. Communication, trust, flatter organization structures and supportive information systems are evident in the corporate culture of both airlines and according to Al-Alawi et al. (2004) are imperative factors for knowledge sharing to take place. MAS and AirAsia are using their intranet and other informal communication channels such as email, memos and bulletin boards to breakdown communication barriers. Silo mentality is counterproductive to the sharing of knowledge as the focus is inward and information communication is vertical. Acknowledging this, MAS has stressed on open and honest communication, effective consensus building and teamwork. This includes setting up a formal whistle-blowing policy, cross-functional business committee teams, constant communication and disclosure of business plans to employees. Its CEO heads the special committee tasked with transforming MAS’s corporate culture and sends emails to employees in his effort to communicate his new vision for the company’s culture. Meanwhile, since its takeover, AirAsia has always practiced open management and provides above average industry disclosure (AirAsia, 2007). AirAsia’s informal team culture also helps organizational members to bond, which according to Nonaka (1994), helps to facilitate knowledge sharing. 4.0 STRATEGIES FOR THE FUTURE USE OF KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT Effective implementation and application of KM among organizations are critical in the current knowledge-based economy. Moreover, in the current climate of continuous change and uncertainty, airlines face critical problems and serious challenges (Doganis, 2006). New knowledge (especially strategies) has to develop regularly in order to stay competitive in the industry. The future success of airlines will be largely dependent on how quickly and flexibly airlines respond to both competitive and market changes (Franke, 2004). Competitive advantage as mentioned by Porter (2001) can be achieved through operational effectiveness and strategic positioning. The firm’s unique knowledge provides the main source of its competitive advantage; allowing it to combine conventional resources in distinctive ways and provide superior value to customers (Saito et al., 2007). It is believe that ICT will continue to be the central element in most knowledge management implementations in this competitive market. ICT will help airlines to automate and streamline processes to reduce complexity and costs as well as to provide greater convenience to the transportation of passengers and freight. Through the integration of knowledge management system and customer relationship management system, ICT will assist airlines in enhancing their transaction-data processing, to make better informed decisions, value-added customized products and services, improve customer-based knowledge and value-driven relationship building. ICT will support both codification and personalization knowledge management strategy which it is used to create, capture, process, store and disseminate knowledge to organization members and other authorized parties. Instant messaging, chat rooms, and expertise location applications for example, provide individuals with tailored learning for more effective knowledge transfer. Social networks that form the basis of an online corporate-wide directory are embedded with instant messaging and e-mail links that provides a valuable resource for employees that go beyond the corporate directory (Powers, 2006). This will enable employees to locate a network 18 of experts to collaborate with or get help from better informed people to solve business problems or form communities of practice. Another ICT device, the asset management solution is a knowledge sharing program which has a series of repositories that contains intellectual capital, key resources, and discussion forums that all support the business and provides a place for staff to access and retrieve knowledge. In short, communication and collaboration technologies like video conferencing and groupware will assist knowledge creation at the group level (Saito et al., 2007). Continued advancements in pricing and revenue optimization system will help airlines to maintain their competitiveness and increase their profit margin. Promising technologies like radio-frequency identification (RFID) when realized will also bring significant improvements to FSC’s baggage handling system (MAS, 2007b). However, for strategically important knowledge to be distributed rapidly around organizations, ICT based knowledge management system needs to be combined with learning from direct experience. Organizational learning is vital as airlines seek to acquire new knowledge and upgrade their core competences in order to give them competitive advantage over rivals. This can be achieved through many means such as acquiring more knowledge workers, training and development, knowledge sharing, strategic alliances, corporate intelligence, e-learning, benchmarking, and learning from direct experiences. It is highly useful for airlines to adopt a learning cycle framework which combines both active and passive stages of learning. According to Honey and Mumford (1989), the learning process will help organizations to learn more effectively. Successful KM leaders like BP use the framework to capture lessons before, during and after any event (Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC), 2008). The learning process can be supported by simple process tools embedded within the company’s intranet with lessons arising from the learning loop agreed and distilled by a community of peers across the organization that has a stake in agreeing and defining organizational best practice (SAIC, 2008). Both specific and generic lessons are then incorporated into special folders on the corporate intranet, where they represent a living focus for the company’s experience around strategic and operational areas (SAIC, 2008). This however will not truly give airlines the competitive advantage that they seek from their learning processes. In order to achieve this, organizational learning must be carefully charted and be given a strategic perspective by knowledge experts such as a Chief Knowledge Officer (CKO). The CKO identifies the organization’s knowledge needs (knowledge sourcing); finds ways to meet that need (knowledge abstract); identifies and refines various ideas and principles into specific outcomes (knowledge conversion), shares and distributes the knowledge (knowledge diffusion) as well as regularly monitoring and accessing the necessity of new knowledge development. Acquiring knowledge workers is also the core factor for airlines to achieve and sustain competitive advantage. Knowledge workers are value creators and value adders to organizations, and their major contributions come from their abilities to process and apply knowledge and information (McFarlane, 2008) to create distinctive advantage for organizations and thus, achieve competitive advantage. In order to fully capitalize on the vast amount of knowledge captured within their knowledge repositories, local airlines need to assign dedicated experts such as a CKO to leverage organization-wide knowledge. The creation of a CKO position also sends an important signal to 19 the organization that knowledge is an asset to be shared and managed (Stuller, 1998). However, this can only be implemented effectively within a knowledge- friendly organization structure with an existing strong knowledge culture. Great concern has been raised regarding the protection of potential intellectual capital lost due to staff turnover (DeLong, 2004) and to ensure continued organizational effectiveness, airlines need to preserve their corporate memory by capturing knowledge and facilitating the transfer of both explicit and implicit knowledge between staff (Al-Hawamdeh, 2002). Possible KM tools and techniques to deal with this problem include the use of ICT, meetings, mentoring, learning logs, and job profiling. KM will continue to play a critical role in managing customer relationship and competitive intelligence (Al-Hawamdeh, 2002), focusing on the speed and manner in which information is being collected, processed and disseminated to the right people, at the right time and right place and how airlines will best respond to such information in competitive terms. Airlines will also be looking into how to encourage knowledge sharing within the organization and build a supportive culture to enable this. As most KM models are formed in the context of Western framework and management practices, local airlines may need to raise awareness and understanding of KM in order to reduce people’s reluctance to share their knowledge (Chowdhury, 2006). This can be done through various means such as corporate-wide campaigns, employee education, leadership by example, and appropriate reward systems. Although the industry has been promoting a culture of transparency, trust and teamwork, the practice of knowledge sharing is still at an early stage. Hence future KM efforts will see the implementation of groupware that will promote greater collaborative efforts and assist in creating and supporting communities of shared interest and information need. Knowledge repositories will continue to be of importance to airlines and in the near future should include lessons learnt from best and worst practices and other relevant information. A knowledge transfer department or other infrastructure should also be considered to oversee the development and maintenance of the organization’s knowledge base (Liebowitz, 1999). Social networks whose features include message boards, blogs, live chat rooms, and podcasts will help to breakdown hierarchical barriers and promote informal communication channels. This will in turn help to create, coordinate, and transfer organizational knowledge. In order to ensure a knowledge sharing culture, airlines will also need to maintain their lean, flexible organization structure and motivate their people to share knowledge by rewarding those who contribute useful information into the system. 5.0 CONCLUSION The knowledge era business environment has made businesses heavily reliant on knowledge to stay competitive in an industry. The amount of information created is overwhelming and the knowledge produced has become more complex and complicated. This paper discusses the basic, yet important aspects of KM for the airline industry. Our literature studies concluded that generic knowledge is necessary to run the industry’s complex daily operations whereas specific knowledge is imperative for airlines’ competitive advantage. MAS and AirAsia, which operate in an oligopoly market structure in Malaysia practice KM to support their respective competitive business and strategies. Their oblique approach to KM does not necessarily mean KM is being perceived as of low importance in the industry, but rather as something that 20 requires gradual application and implementation by systematically incorporating KM tools and techniques into their existing stage of business. ICT has been used in innovation, knowledge development, knowledge utilization and knowledge capitalization, which in turn has produced unique business strategies, lowered the cost of operation of airlines and increased organizational efficiency. Meanwhile, organizational learning has led to new, improved modus operandi and new business development for both airlines. Similarly, both airlines manage and leverage their intellectual capital to their maximum advantage. However, with the challenging road ahead in the airline industry there is an increasing need to maintain competitive advantage and to progress beyond the industry’s current state of KM. AirAsia’s KM practices will need to support its expanding business besides sustaining its cost-leadership advantage in the industry; whereas MAS will have to face challenges of its hybrid strategy of competitive pricing strategies and differentiation which may allow the market to recognize its branding efforts as a five-star value carrier. Hence the “now” and “then” gaps represent the future void that KM needs to fill today. REFERENCES Airasia (2007), [Online] <www.airasia.com.my> [Accessed on 23 August 2008]. Argyris, C. and Schon, D. (1978), “Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective”, Addison Wesley, Reading, US. AirAsia, 2007, Company annual report year 2007, AirAsia, Malaysia. Al-Alawi, A.I., AlMarzooqi, N.Y. and Mohammed, Y.F. (2007), “Organizational culture and knowledge sharing: Critical success factors”, Journal of Knowledge Management, 11(2), 22-42. Al-Hawamdeh, S. (2002), “Knowledge management: Re-thinking intellectual management and facing the challenge of managing tacit knowledge”, Information Research, 8(1), paper no. 143 [Available at http://InformatonR.net/ir/8-1/paper143.html] Chowdhury, N. (2006), “Building KM in Malaysia”, Inside Knowledge, 9(7), [Online]http://www.kmtalk.net/article.php?story=20060727043623849 [Accessed on: 25 April 2008]. Christensen, P.H. (2007), “Knowledge sharing: moving away from the obsession with best Practice”, Journal of Knowledge Management, 11(1), 36–47. Davenport, T.H. and Prusak, L. (1998), “Working knowledge: How organizations manage what they know”, Harvard Business School Press, US. DeLong, D.W. (2004), “Lost knowledge: Confronting the threat of an aging workforce”, Oxford University Press, US. Doganis, R. (2006), The Airline Business, 2nd ed., Routledge, London. 21 Franke, M. (2004), “Competition between network carriers and low-cost carriers-retreat battle or breakthrough to a new level of efficiency”, Journal of Air Transport Management, 10(1) 1521. Honey, P. and Mumford, A. (1989), “The Manual of Learning Opportunities”, Honey, P (Ed.), Ardingly House, Maidenhead. Ingram, P. and Baum, J.A.C. (1997), “Chain affiliation and the failure of Manhattan hotels”, 1898-1980, Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 68-102. Kho, C. Aruan, S.H., Tjitrahardja, C. and Narayanaswamy, R. (2005), “AirAsia- Strategic IT initiative”, Faculty of Economics and Commerce, University of Melbourne, Australia. [Online] <http://sandygarink.tripod.com/papers/AA_SITA.pdf>. [Accessed on: 24 April 2008] Liebowitz, J. (1999), Knowledge management handbook, CRC Press, New York. MAS 2007, Business turnaround plan, <cms.malaysiaairlines.com/mys/eng/about_us/investor_relations/MAS [Accessed on: 25 April 2008]. MAS, [Online Way_F.pdf -> MAS 2007b, Business transformation plan, MAS, [Online] <www.malaysiaairlines.com/getfile/78aa4d9c-4963-40838063be16e50d4b5a/BTP2.aspx>. [Accessed on: 25 April 2008]. McDermott, R. and O’Dell, C. (2001), “Overcoming cultural barriers to sharing knowledge”, Journal of Knowledge Management, 5(1), 76-85. McFarlane, D.A. (2008), Effectively managing the 21st century knowledge worker, Journal of Knowledge Management Practice, 9(1), [Online] <www.tlainc.com/articl150.htm> [accessed on 24 Sept 2008]. Nonaka, I. (1991), “Knowledge-creating company”, Harvard Business Review, 69(6), 96-104. Nonaka, I. (1994), “A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation”, Organization Science, 5(1), 14-36. O’Connell, J.F. and Williams, G. (2005). “Passengers perception of low cost airlines and full service carriers: A case study involving Ryanair, Aer Lingus, AirAsia and Malaysia Airlines”, Journal of Air Transport Management, 11(4), 259-272. Pemberton, J.D. and Stonehouse, G.H. (2000). Organisational learning and knowledge assets – an essential partnership, The Learning Organization, 7(4), 184-194. Porter, M.E. (2001). “Strategy and the Internet”, Harvard Business Review, 79(3), 62-78. 22 Powers, V. (2006), “IBM’s KM Strategy”, KM World [Online] http://www.kmworld.com/Articles/ReadArticle.aspx?ArticleID=16907&PageNum=2> [Accessed on: 19 April 2008]. Ricart, J.E. and Wang, D. (2005), “Now everyone can fly: AirAsia” Asian Journal of Management Cases, 2(2), 231-255. SAIC.com 2008, KM & British <http://www.saic.com/km/who.html>. Petroleum, [Accessed on 10 May 2008] Saito, A., Umemoto, K. and Ikeda, M. (2007), “A strategy based ontology of knowledge management based technologies”, Journal of Knowledge Management, 11(1), 97- 111. Shepard, S. (2000), Telecommunications convergence, McGraw-Hill, NewYork. Senge, P. (1992), The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization, Century Business, London. Stewart, T.A. (1997), Intellectual Capital: The New Wealth of Organisations, London: Nicholas Brealey Stewart. Stonehouse, J.D. and Pemberton, G.H. (1999), “Organizational learning and knowledge assets”, The Learning Organization, 7(4), 184-193. Stuller, J. (1998), “Chief of corporate smarts”, Training, 35(4), 28-37. Taylor, A. (2008), Lecture slides, University of Abertay Dundee, UK. Whittle, S, (2007), How to use social networks for business gains?, Zdnet http://resources.zdnet.co.uk/articles/features/0,1000002000,39290463-3,00.htm?r=1 [Accessed: 10 May 2008] 23 Appendix 1 (Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation, 5 April 2005) 24