Moxy-Fortiori design.indd

advertisement

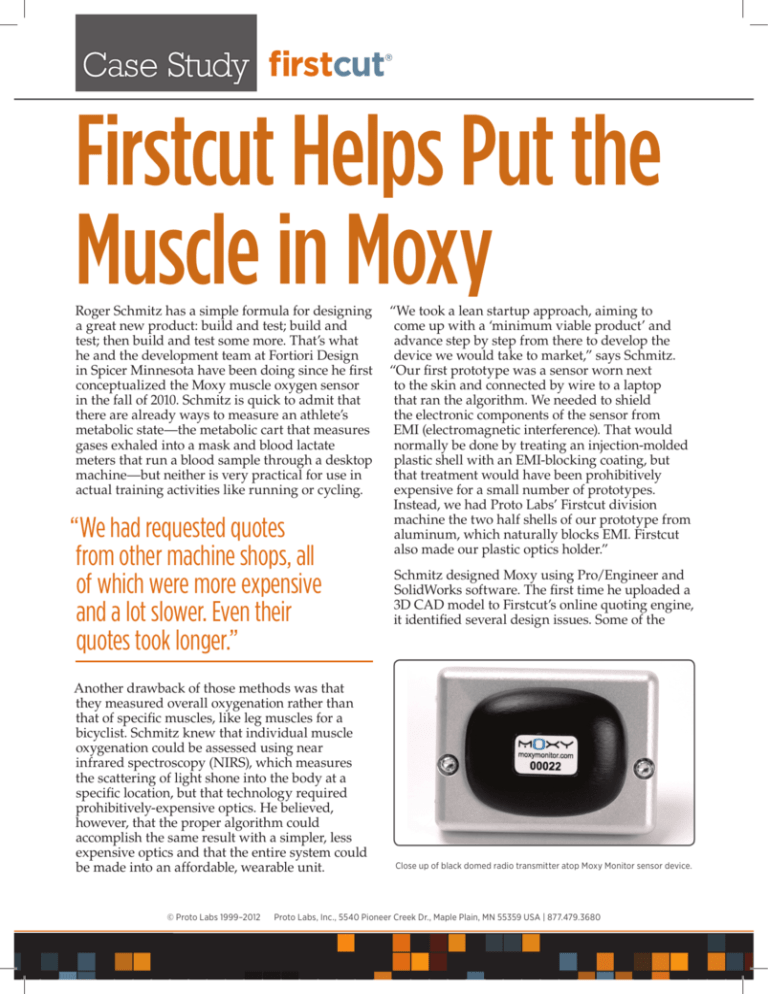

Firstcut Helps Put the Muscle in Moxy Roger Schmitz has a simple formula for designing a great new product: build and test; build and test; then build and test some more. That’s what he and the development team at Fortiori Design in Spicer Minnesota have been doing since he first conceptualized the Moxy muscle oxygen sensor in the fall of 2010. Schmitz is quick to admit that there are already ways to measure an athlete’s metabolic state—the metabolic cart that measures gases exhaled into a mask and blood lactate meters that run a blood sample through a desktop machine—but neither is very practical for use in actual training activities like running or cycling. “We had requested quotes from other machine shops, all of which were more expensive and a lot slower. Even their quotes took longer.” Another drawback of those methods was that they measured overall oxygenation rather than that of specific muscles, like leg muscles for a bicyclist. Schmitz knew that individual muscle oxygenation could be assessed using near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), which measures the scattering of light shone into the body at a specific location, but that technology required prohibitively-expensive optics. He believed, however, that the proper algorithm could accomplish the same result with a simpler, less expensive optics and that the entire system could be made into an affordable, wearable unit. © Proto Labs 1999–2012 “We took a lean startup approach, aiming to come up with a ‘minimum viable product’ and advance step by step from there to develop the device we would take to market,” says Schmitz. “Our first prototype was a sensor worn next to the skin and connected by wire to a laptop that ran the algorithm. We needed to shield the electronic components of the sensor from EMI (electromagnetic interference). That would normally be done by treating an injection-molded plastic shell with an EMI-blocking coating, but that treatment would have been prohibitively expensive for a small number of prototypes. Instead, we had Proto Labs’ Firstcut division machine the two half shells of our prototype from aluminum, which naturally blocks EMI. Firstcut also made our plastic optics holder.” Schmitz designed Moxy using Pro/Engineer and SolidWorks software. The first time he uploaded a 3D CAD model to Firstcut’s online quoting engine, it identified several design issues. Some of the Close up of black domed radio transmitter atop Moxy Monitor sensor device. Proto Labs, Inc., 5540 Pioneer Creek Dr., Maple Plain, MN 55359 USA | 877.479.3680 holes were too deep, there was a minor aspect ratio problem, and some inside corners needed to be radiused. “We made the necessary changes and sent a revised model that Firstcut machined for us,” he says. “We had requested quotes from other machine shops, all of which were more expensive and a lot slower. Even their quotes took longer. The aluminum case parts we got from Firstcut were very cool. It was a complex shape, contoured to fit the wearer’s body on the outside and shaped to fit the electronics inside, but Firstcut’s ballend mills had no problem with it. We called the resulting device Moxy1 and used two prototypes to test runners on a treadmill and adjust our algorithm until we were getting consistent, stable results. Our next goal was to eliminate the wire and the laptop to come up with a wearable device. “Another nice thing about Firstcut is that they could handle the draft in our designs, which most machine shops can’t.” “We appreciate the short lead times and transparency in quoting at both Proto Labs divisions.” The company is now in the final stages of development with a team of about a dozen and partnership with a professional training facility in San Diego. “We’re getting the final bugs worked out,” says Schmitz. “Moxy needs to be 100 percent waterproof, both to withstand sweat and, ultimately, to be used by swimmers, so the shell will have to be fully gasketed. The next prototype version of the shell will be injectionmolded plastic with an EMI-blocking coating, and the entire device will be extensively drop-tested, vibration-tested, water-tested, and lifecycle-tested. We figure we’ll have to build and break between 50 and 70 units before we really know that it’s bulletproof. We’ll use Proto Labs’ Protomold division, which I’ve used before with great success, for molded plastic parts. We appreciate the short lead times and transparency in quoting at both Proto Labs divisions and expect to easily meet our goal of bringing a fully-tested product to market in summer of 2013.” Moxy2 added a microcontroller to the sensor to do the calculations that had previously been done on a laptop. It had a radio transmitter outside the EMI- shielded shell to send the results to a TI Chronos wristwatch for display, using its own battery for onboard power. The new model required revised shells, which were again machined from aluminum stock by Firstcut. “Since we weren’t tied to the laptop anymore we could start doing serious real-world testing,” says Schmitz. “We figured we’d need about 20 copies, but because Firstcut’s turnaround was so fast we initially ordered just four and waited on the other 16 until we’d identified additional changes that could be incorporated into the next version. Moxy Monitor System: Front and back of sensor shown with watch display. Another nice thing about Firstcut is that they could handle the draft in our designs, which most machine shops can’t. Draft isn’t really needed in machined parts, but when we go into full-scale production it will be required for molded or die cast parts and we wanted our prototypes to be as close to production designs as possible.” © Proto Labs 1999–2012 Proto Labs, Inc., 5540 Pioneer Creek Dr., Maple Plain, MN 55359 USA | 877.479.3680