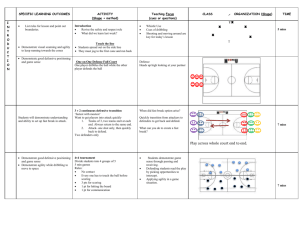

2010 - World Organisation Against Torture

advertisement