Charles Zavitz - Canadian Friends Historical Association

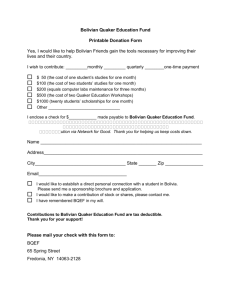

advertisement