'Nanny State' Politics: Causal Attributions about Obesity and Support

advertisement

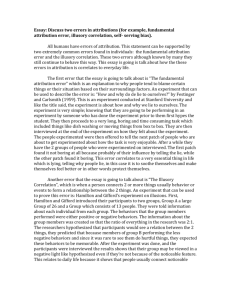

‘Nanny State’ Politics: Causal Attributions about Obesity and Support for Regulation Donald P. Haider-Markel, University of Kansas, Mark R. Joslyn, University of Kansas & Matthew Miles, Brigham Young University--Idaho Department of Political Science 1541 Lilac Lane, 504 Blake Hall University of Kansas Lawrence, KS 66044 Email: dhmarkel@ku.edu Phone: (785) 864-9034 Fax: (785) 864-5700 Abstract: Individuals develop causal stories to explain the world around them, including events, behaviors, and conditions in society. These are narratives that attribute causes to controllable components, such as individual choices, or uncontrollable components, such as broader forces in the environment. We employ attribution theory to understand how group identity and individual characteristics may shape causal attributions about obesity. Based on previous empirical findings we subsequently argue that attributions can explain support for government regulation of the food industry. We test our hypotheses using individual level data from several national surveys of American adults. Our findings suggest that group identities and individual characteristics predispose people to make certain attributions about obesity, and these attributions are correlated with attitudes towards government regulation. We suggest that the issue of obesity is becoming increasingly politicized, making the obesity crisis in America more difficult to address through private or public actions. Manuscript prepared for presentation at the Florida State University Symposium on Regulation in the States, February 20-21, 2014, Tallahassee, FL. 1 We spend considerable time seeking to understand how conditions and events come to be. This effort to attribute causes underlies much of the debate on any given policy issue and structures the opportunities or roadblocks for government action. Policy choices are often constructed around a causal theory that suggests proximate causes for given problems. People search for causes not only for understanding but also to punish, compensate, protect, blame, and legitimize (Brandt 2012; Stone 1997). Political actors in fact utilize causal inferences as tools to shape alliances and allocate costs and benefits; and as some issues increase in salience, our efforts to attribute cause increase as we strive to understand potential solutions. Take for example the rise in obesity and the related increase in child and adult diabetes. By some this is viewed as a public health epidemic, requiring immediate government intervention. Others recognize the problem but balk at the notion that the issue doesn’t reside in the choices made by individuals (Barry, Brescoll, and Gollust 2013). Indeed, some even go so far as to suggest individual choice is more important to protect from the ‘Nanny State’ than it is to protect individual health (Harsanyi 2007). In our ongoing search for causal attributions individuals may use a variety of cues, including ideology and social groups, as a means for reducing the attributional options. Indeed, social identity theorists have long suggested that individuals use their reference group narratives to interpret and understand the world around them. Those with a stronger group identity will be more likely to share elements of group consciousness and thereby have a shared understanding of events. But even when group cues are unclear or lacking on a particular issue, those with a strong group identity are more likely to evaluate an issue in ways that are relevant to their group (Conover 1988). 2 In addition, as issues become politically salient social identity groups are more likely to stake out positions on the issue to gain social or political advantage (Haider-Markel and Joslyn 2013). In the case of political parties and their identifiers, communicating the group’s position on salient issues can be especially relevant (Green, Palmquist, and Shickler 2002; Layman, Carsey, and Horowitz 2006). And as party identities shape attributions, attributions are also then likely to shape attitudes towards a targeted group as well as potential policy options and policy preferences (Barry et al. 2013; Brandt 2012; Haider-Markel and Joslyn 2008). Our project explores the role of social identities and individual characteristics in shaping attributions about obesity and how this role may have evolved in recent years. Beyond group identification we also examine the role of self-serving attributions, or predispositions paint an individual’s current status or condition in a more positive light. We then use attributions about obesity to explain emotions attitudes towards overweight individuals and, subsequently, policy proposals advocated to reduce obesity in society. For each of these analyses we examine data from a variety of surveys of American adults conducted between 2003 and 2013. We begin our discussion with a review of attribution theory and its particular application to understanding obesity and potential policy responses. Our analysis suggests that partisan identities have increasingly shaped attributions about obesity while self-serving attributions are a consistent predictor. Additionally, partisan identities and attributions shape attitudes towards the obese and potential policy responses concerning obesity in society. We argue that our discussion and results favor developing a stronger link between social identity theory and attribution theory. 3 Attribution Theory and Social Identity In his formulation of attribution theory Heider (1944, 1958) emphasized the importance of a controllable, predictable world. People strive to control their environments, and to understand what conditions give rise to a specific behavior or outcome allows individuals to anticipate and respond accordingly (Wortman 1976). People are driven by a practical concern to stabilize and simplify their environments. Presumably knowing what causal factors give rise to specific outcomes allows people to control the likelihood of that outcome, or at least forecast its emergence. In addition, attribution theory suggests that people behave the way they do because of who they are, and because of the types of circumstances that give rise to their behavior. When people formulate an attribution about another individual, for example, they are determining whether behavior is derived from some external or situational element that influences the person or from internal or dispositional forces. Namely, did the Senator speak favorably about the environment because she truly believes in protecting the environment (dispositional), or was she simply pandering to a liberal audience (situational)? Does sexual orientation emerge from social conditions that may foster a specific preference or are people born with an identifiable genetic disposition? Additionally are racial differences in income due to social and political conditions that disadvantage African Americans or are racial distinctions derived from genetics differences? Each question concerns the contribution to behavior of situation/external forces and dispositional/ internal forces; and this duality is a key feature of attribution theory. 4 The distinction between external and internal forces in fact led political scientists to examine partisan and ideological attributions about a variety of public policy matters. For example, researchers discovered that Democrats and Republicans employed different causal explanations for poverty (Iyengar 1991; Pellegrini et al. 1997). Democrats attributed poverty to environmental factors – institutional biases and market forces – whereas Republicans believed that individuals were to blame for their poverty. Researchers also found that conservatives attributed poverty to individual dispositions while liberals perceived causes in situational sources (Griffin and Oheneba-Sakyi, 1993; Zucker and Weiner 1993). Hughes and Tuch (2000) discovered a similar relationship, showing that structural attributions, as opposed to individualistic, were important predictors of support for race-based policies such as affirmative action and welfare. Evidently, to regard government as the solution, one must first perceive larger environmental factors as the cause of the problem. As Moscovici (1984, 50) aptly observed, “…in societies we inhabit today, personality causality is a right-wing explanation and situation causality is a life-wing explanation.” These studies suggest that it is particularly valuable to conceptualize causal attributions in their functional role (Forsyth 1980). Motivated to attribute in a manner consistent with political predispositions, people select the attribution that squares with their priors (HaiderMarkel and Joslyn 2008; Joslyn and Haider-Markel 2012). A Republican’s tendency to blame the poor for their poverty justifies a limited role for government and reinforces the cherished individualism ethic. Democrats, by contrast, view the poor as victims of larger social and market forces and thus government is the vehicle through which inequality can be addressed. In both instances, causal attributions arise from and justify existing beliefs. Moreover, causal 5 attributions appear to be utilized by political actors as “….essential political instruments for shaping alliances and for settling the distribution of benefits and costs” (Stone 1997; 189). These factors highlight the political implications of causal attributions and the need to examine genetic attributions, an increasingly popular and important category of causal reasoning. Related research on social identity emphasizes the role of inter-group dynamics in shaping attributions. There is a strong tendency for in-group members to attribute positive characteristics to fellow members while the out-group receives less charitable and often negative attributions (Allport 1954; Brewer 1999; Tajfel and Turner 1986). Out-group behaviors are frequently attributed to negative internal dispositions with important situational factors ignored. A positive behavior by the in-group may be viewed as a general disposition by ingroup members but the same behavior by the out-group will be considered a special case and often attributed to chance (Tygart 2000; see also Pettigrew 1979, 1980). Strong group identity can also shape attributions that then influence behavior. For example, Miller et al. (1981) provided evidence that people who attributed systemic forces to their group’s relatively disadvantaged position in society were more likely to vote than people who attributed their group’s disadvantage to individual-level factors. Interestingly, the development of a social identity connected to a referent group is associated with the availability and communication of a politicized collective identity. Such an identity is salient to individuals when they see themselves as “self-conscious group members in a power struggle on behalf of their group” (Simon and Klandermans 2001, 319). “When issues contain clear cues for a group that a person identifies with, the assessment of the issue will probably be biased in the pro-group direction. Where 6 group cues are weak, people with strong group identifications may, none the less, evaluate an issue in group terms relevant to them; consequently, various individuals may be influenced by different group identifications on the same issue (Conover 1988, 63).” From this perspective, collective group identity is social constructed and communicated to group members. This collective identity contains a worldview with attributions that explain the position of the group in society as well as the positions of other groups. For individuals that identify with the group, this communicated worldview can shape attributions about conditions or events that may only indirectly be related to the group (Conover 1988). This might be especially true for explaining situations in areas where many people feel uncertain, such public health problems, including obesity. Social psychologists believe that when people face uncertainty about causal relationships, they often apply causal schemas. Causal schemas derive from past experiences as well as communicated collective group identity and are “…general conceptions the person has about how certain kinds of causes interact to produce a specific kind of effect” (Kelly 1972, 151; see also Conover 1988). The schema then provides a cognitive short-cut, which when applied shapes causal attributions. Additionally, some attribution studies point to the power of language and social context to effect attributions. Causal inference can turn on how an event or condition is characterized and the dynamics of social communications (Antaki and Naji 1987; Fiedler and Semin 1988; Slugoski 1983). Recent developments in public opinion research offer similar conclusions. Because individuals typically rely on heuristics, which can include group cues, to compensate for their lack of knowledge, the choice of words used to describe an issue can significantly change attitudes and opinions about that issue (Cobb and Kuklinski 1997). Specific messages or 7 issue frames have the potential to prime respondents, making certain considerations more accessible in memory and thereby influencing how people understand a given issue (Iyengar and Kinder 1987). Applying this logic to causal attributions, Iyengar (1991) demonstrated that the manner in which TV news frames stories of poverty, crime, and terrorism led audiences to blame poverty on individual as opposed to societal level sources. Likewise, recent research suggests that the manner in which child obesity is framed can influence support for proposed policy solutions (Barry et al. 2013) Related to these findings is the well-known axiom that the public’s attention to politics is intermittent and the causal logic characterizing political affairs is unstable (Stone 1997). As a consequence people seek political authorities to reduce their uncertainty. And, it appears that group leaders, political party elites, and other political elites are well equipped to perform this role, providing talking points and ready-made accounts that influence the public’s causal reasoning (McGraw 2001; Schneider and Jacoby 2005). Groups and Attributions about Obesity To summarize, this line of research in political science and social psychology suggests that attributions are not simply matters of the mind but rather social, political, and communicative in nature. Causal inferences are sensitive to social context, media content and political elite explanation. The very causal schema that people apply under uncertainty may in fact derive from past exposure to group communications. We in fact suggest that group identification implies specific causal schema. 8 In thinking about why some people overweight while others are not, we are faced with basic attribution questions. Likewise, when public health officials declare an ‘epidemic of obesity’ in some populations, we are pressed further to think about societal solutions that are dependent on a casual theory of attribution. Should we attribute obesity to family history and/or genetics, or should we attribute it to individual choices about diet and exercise? As a potential public health issues, should the causal theory about increased obesity rates be linked to family history and/or genetics, to individual choices, or to a social context where inexpensive high-fat food is readily available and inexpensive? Our path to this answer suggests that our group identities and individual characteristics help shape our answers to these questions. Our primary focus here is on partisans as a social identity group and weight-based groups based on their potential individual based incentive to make particular attributions. Among partisans attributions can be particularly polarizing. Existing research suggests that Democratic perspectives on causes typically do not focus on individuals or individual choices. In the Democratic worldview individuals have agency, but more often than not are subject to forces outside their own control. Those forces might be based in biology, social context, or some combination (Haider-Markel and Joslyn 2008). The Republican worldview on causes is almost completely opposite; Republicans tend to put the locus of control precisely on the individual and argue that an individual condition or event is simply a result of personal choices and motivation (Joslyn and Haider-Markel 2012). At the same time those who are overweight have some incentive to attribute their situation to forces outside of their control, such as genetics, biology, or the social context—in other words, outside of individual control. Those without weight problems, meanwhile, have 9 self-esteem reinforcing incentives to suggest their condition is a function of individual choices in food intact and exercise, framed even more persuasively as self-control or self-discipline. Such incentives are called self-serving attributions and function to bolster self-esteem in regards to an individual’s situation. Although women as a group are no more likely than men to have weight issues, we do know that women are inclined to make attributions that suggest broader forces are the cause of some event or phenomenon and not the result of actions by an individual (Gilligan 1983). Indeed, Worden (1993, 206) suggests that women tend to develop an “ethic of care,” with a view that “society as an interdependent and interconnected web of personal relationships.” In this perspective events and conditions are the result of broader systematic forces, generally outside the control of one individual. Such causes could be hereditary or biological, or could result from a broader social context. Men, meanwhile, have an “ethic of justice,” which tends to focus on self-determination, self-discipline, and personal physical strength as driving forces in determining outcomes (Gilligan 1982, 166; Stanko 1990, 110). As such, we would expect women to place causes for obesity outside of the control of the individual while men should be more likely to attribute obesity to individual choices and behavior. Issue Salience and Partisanship We first briefly explore the salience of the issue and the role of partisanship. Recall that we expect political parties to stake out positions on salient issues and communicate those positions to their members, thus creating differences between partisan identifiers. 10 A quick search of the term ‘over weight’ using Google Trends news headlines from 2004 to 2014 indicates that the issue has been very salient over the past decade with a general trend in increasing salience. [Insert Figure 1 About Here] Second, a search of the RoperExpress Data Base reveals few questions asking about obesity until after 2005. Only one poll asked about attributions before obesity before 2006 and the first poll to ask about genetic causes for obesity is a 2006 poll from the Pew Research Center. Given our discussion above we expect that earlier polling on the causes of obesity are unlikely to uncover partisan differences in attributions, while more recent polls should uncover such differences with the onset of partisan competition on the issue. Making use of data from a March 2006 Pew Center for the People and Press survey of American adults we can see that partisans did not make distinctly different attributions about obesity. Pew asked: “For each item I name, please tell me how important this is as a reason many Americans are very overweight—very important, somewhat important, not too important, or not at all important: Genetics and hereditary factors?” A simple Pearson’s correlation between party identification and respondents answers reveals a correlation of .014 (P value = .269). Likewise when asked about the following reason “Lack of willpower about what to eat,” a simple Pearson’s correlation between party identification and respondents answers reveals a correlation of .011 (P value = .740). Therefore, as recently as 2006 there was no statistically significant difference between partisan identifiers and attributions for obesity. 11 However, as we will see partisan predispositions about obesity have become more established just as a variety of social groups have begun to think about the potential policy choices to address an apparent growing obesity problem in the U.S. Recent Attributions about Obesity and Implications Our next step is to more fully explore the influence of social identities on attributions about obesity and the subsequent influence on attitudes towards overweight people and policy prescriptions for addressing obesity. To do this we make use of a unique dataset based on a June 2013 survey of American adults. A probability sample of 1,596 subjects was recruited by the authors through Research Now to participate in a study measuring political attitudes. Of these, 27% were Republicans and 32% were Democrats. The survey was fielded online from June 18-June 21, 2013. The sample resembles the U.S. population in most respects, including age, gender, income and political interest, but leans Democratic, liberal, and attentive to politics (see methodological Appendix); we believe this left-leaning sample will allow for a more conservative test of our central propositions. Dependent Variables Our first dependent variable is an attribution for being overweight. Our unique survey asked respondents “Thinking about the reasons some people are significantly overweight or obese, do you think it is due more to: Genetic factors a person is born with (14%) or, Eating and lifestyle habits (86%).” When limited to two choices respondents overwhelming made an individualistic attribution that placed the locus of control on the individual and not on her 12 biology or genetics. However, a large enough number of respondents (218) did make a biological attribution for a reasonable comparison between groups. Our second set of dependent variables capture emotional responses or attitudes towards overweigh people. We asked respondents “How unsympathetic or sympathetic are you towards obese people? Very unsympathetic, Somewhat unsympathetic, Somewhat sympathetic, or Very sympathetic?” Later in the survey we also asked “How angry are you towards obese people? Very angry, Somewhat angry, or Not at all angry?” We also posed the following question as a feeling thermometer questions: We’d like to get your feelings toward some of our organizations and groups who are in the news these days. We’d like you to rate groups using something we call the feeling thermo meter. Ratings between 50 degrees and 100 degrees mean that you feel favorable and warm toward the group. Ratings between 0 degrees and 50 degrees mean that you don't feel favorable toward the group and that you don't care too much for that group. You would rate the group at the 50 degree mark if you don't feel particularly warm or cold toward the group.” We expect that those making a genetic attribution will be more likely to show sympathy, have higher feeling thermometer scores, and will be less likely to show anger towards overweight people. Our third set of dependent variables examines preferences towards policies directed at overweight people and/or the rising level of obesity in society. We first asked: “Do you think companies should be allowed to refuse to hire people just because they are significantly overweight, or not? Yes, should, or No, should not.” Next we asked a series of policy related questions and the extent to which the respondent favor or opposed each on a four point scale: 1) How you strongly would you favor or oppose holding the fast food industry legally 13 responsible for the diet-related health problems of people who eat fast food on a regular basis?, 2) How you strongly would you favor or oppose government regulations that limit saturated fat content in food?, and 3) How you strongly would you favor or oppose an extra tax on foods that are high in saturated fat content? Each of these questions is coded with strongly favor as four and strongly opposed as one. Independent Variables Our primary independent variable for the attitudes toward overweight people and the policy questions is the response to our question about attributions. Recall group identification variables are central to our analysis of understanding attributions. Our survey did not include any strength of identity questions but it did ask respondents to classify themselves based on a number of categories, including race and ethnicity, gender, income and class, and partisanship. For our models predicting attributions we include variables accounting for each of these groups. Here we are primarily interested in party identification and gender. Party identification is measured on respondent self-placement on a seven-point scale. Since responses from Democrats and Independents were similar, we recoded the measure with all Republicans coded as one and all others coded as zero. We expect that Republicans will be less likely to make a biological attribution and be less likely to support government policies intended to reduce obesity. Race is measured with a dichotomous variable coded one if the respondent indicated Caucasian for race, and zero otherwise. We measure gender with a variable coded one for 14 female and zero for male. We have no clear expectations for race but given that women are more likely to identify attributions that are outside of the control of an individual (HaiderMarkel and Joslyn 2008; Weiner et al. 2011), we expect that women will be more likely to make a biological or genetic attribution. Women should also be more likely to support government policies intended to reduce obesity. We also account for respondent education level, and age. Education is simply a seven point scale with ‘grade eight or less’ coded as one, and ‘post-graduate training’ coded as seven. Age is the respondent age in categories with 18-25 as one, and 65 and older as six, with the remaining categories 26 to 64 as exclusive nine to ten year categories. Although the more educated tend to make non-individualistic attributions, on some issues, such as attributions for success in life, they do make self-serving individualistic attributions (see Haider-Markel, Joslyn, and Miles 2013). As such we have no clear expectations for education level or for age. Finally we asked respondents about self-assessed weight; we asked: “In your view are you: Very underweight, Underweight (weigh less than you should), About the right weight, Overweight (weigh more than you should), or Very overweight?” Almost 51 percent of the respondents considered themselves at least overweight. For the analysis we coded those indicating they are about the right weight or underweight as zero and those who indicated overweight or very overweight as one. We expect to observe a self-serving attribution whereby overweight people would prefer – and are motivated to select – the genetic attribution, as that cause removes much of the blame for one’s own obesity and may in fact justify the status quo individually and in society. Results and Discussion 15 Attributions and Emotions towards Overweight People First we examine how attributions might influence emotional reactions to persons who are overweight or obese. We asked respondents “How unsympathetic or sympathetic are you towards obese people? Very unsympathetic, Somewhat unsympathetic, Somewhat sympathetic, or Very sympathetic?” Later in the survey we also asked “How angry are you towards obese people? Very angry, Somewhat angry, or Not at all angry?” The genetic attribution implies less control over behavior and therefore more positive emotional states toward the obese. By contrast, a lifestyle attribution suggests volition and thus control – hence negative feelings toward obese. Therefore we expected that we should observe higher reports of sympathy and less anger toward obese people among those who attribute obesity to genetics than among those who attribute obesity to lifestyle. This is indeed what we observed: among those making genetic attributions we saw much higher levels of sympathy (81%) and non-anger (88%) than among those who made lifestyle attributions (55% sympathy and 82% non-anger). Perhaps this is intuitive: if obesity is not perceived as controllable then people feel greater sympathy toward others with the condition and certainly do not hold malice. By contrast, lifestyle attributions suggest a choice and people carry at least some anger (18%) and lack sympathy (45%) towards overweight people. Particular attributions clearly generate different emotional responses towards overweight people. But to what extent do these attributions and emotional responses shape policy preferences? We asked respondents “Do you think companies should be allowed to 16 refuse to hire people just because they are significantly overweight, or not? Yes, should (25%), or No, should not (75%).” A simple path analysis reveals a -.05 correlation between making a genetic attribution and anger at obese people, while there is a .20 correlation between being angry at obese people and believing companies should be able to discriminate in hiring obese people.1 Likewise there is a .17 correlation between making a genetic attribution and feeling sympathy toward obese people while there is a -.27 correlation between feeling sympathy toward obese people and believing companies should be able to discriminate in hiring. Finally, the direct correlation between making a genetic attribution and believing companies should be able to discriminate in hiring is -.09, so relatively weak compared to the emotional responses and support for discrimination. Next we examined the relationship between attributions and ratings of obese people on the Feeing Thermometer, and subsequent belief that companies should be able to discriminate in hiring obese people.2 A path analysis reveals a .12 correlation between a biological attribution and the Feeing Thermometer rating. The correlation between a respondent’s Feeling Thermometer rating and a belief that companies should be able to discriminate in hiring obese people is -.25. Thus, it is clear that attitudes towards obese people are shaped by attributions and these attitudes subsequently can shape attitudes about the behavior of private companies. We turn now to multivariate analysis and broader policy proposals meant to address obesity in society. Multivariate Analysis 1 2 All reported correlations are statistically significant at p <.05 or better All reported correlations are statistically significant at p <.05 or better 17 Table 1 provides estimates derived from each equation. We first predict attributions about obesity using our independent variables and then we add the attribution response to our models predicting policy preferences. The results for the model predicting the likelihood of making a genetic attribution about obesity are displayed in column one of the table while the results predicting policy preferences are displayed in the remaining four columns. As predicted partisanship is a significant predictor of attributions with Republicans significantly less likely to make a genetic attribution for why some people are overweight. Meanwhile, respondents that consider themselves at least somewhat overweight are more likely to make a self-serving attribution that biology determines weight. Our other predictors do not appear to significantly influence the likelihood of making a particular attribution. [Insert Table 1 about Here] Turning to policy preferences in column two of Table 1 the results indicate that making a genetic attribution and partisanship influence the likelihood of making a particular policy preference. Respondents making a genetic attribution for obesity were significantly less likely to indicate that private employers could refuse to hire someone who was obese. Meanwhile, Republicans were significantly more likely to indicate that private employers could refuse to hire someone who was obese. These results are robust and remain even if we include the attitudes towards obese people discussed earlier, suggesting that attributions and partisanship are powerful predictors of support for employment discrimination. 18 The results also indicate that respondents that classify themselves as overweight are less likely to support employment discrimination as are women. Both results confirm our expectations. Interestingly those older respondents and those with more education were significantly more likely to support private companies discriminating against overweight individuals. Although these results were not expected, it could be that older respondents and the more educated are attempting to factor in the insurance and lost productively time resulting from hiring overweight employees. Unfortunately our data do not allow us to explore this issue in greater detail. Column three displays the results of our model predicting whether respondents supporting hold the fast food industry legally responsible for obesity. Here our results begin to differ with our expectations. Although Republicans were more likely to oppose this policy measure, those making a genetic attribution for obesity were no more likely to oppose the measure than those attributing obesity to lifestyle choices. And perhaps even more surprisingly, respondents indicating that they are overweight were somewhat more likely to oppose holding the fast food industry legally responsible than were respondents that are not overweight. Since overweight individuals were more likely to make genetic attributions it could be that these same individuals have exonerated the fast-food industry from any culpability for their situation and are therefore even more likely than other respondents to oppose legal sanctions. It also stands to reason that the attribution choices we provided: a biological one or a personal choice attribution, do not point to a contextual attribution that might include the context of what food is available to the consumer. In hindsight it may have been preferable to 19 provide an attribution option for respondents that was completely contextually based and was not linked to biology or individual choices or behavior. The results for the final two policy questions: favoring government regulations on saturated fat and favoring higher taxes on foods with saturated fats, reveal results similar to the model for fast food industry policy. However, there are a few notable differences. Although Republican opposition to these measures is consistent, overweight individuals are more likely to disapprove of government regulations on saturated fat, but are no more likely than others to oppose increased taxes on foods higher in saturated fat. So while overweight individuals, who disproportionally attribute obesity to biology, do not support increased regulation, they are not likely to oppose higher taxes on unhealthy food more than anyone else. More educated respondents were meanwhile no more likely to support regulation, but were more likely to support higher taxes on foods with higher saturated fat. We could perhaps infer that the more educated support an incentive-based policy in this area since they are no more likely to attribute obesity to biology or lifestyle than the less educated. And given the lack of certainty about causes, an incentive-based system might be easier to support than a regulatory system that assumes a contextual or lifestyle choice underlying cause. In summary, our analyses reveal that the influence of partisan weight-based identities shape attributions and some policy preferences. In fact, the partisan influence we observe on attributions for obesity extends to preferences on discrimination by private companies and support for government policies intended to curb obesity. The limitations of our data perhaps do not reveal the full extent to which attributions can shape policy preferences or the extent to 20 which a weight-based identity might shape preferences for policy, but our initial results do provide some directions for additional research. Conclusions People naturally seek to understand why conditions, behaviors, and events come to be; we try to make sense of the world and attribute causes to reduce our own uncertainty. However, in our attempts to understand we face considerable uncertainty about causes and often turn to others for ready-made explanations. Social identity theorists suggest that groups communicate schemas or worldviews that do indeed provide causal attributions. Individuals that identify with these groups are therefore more likely to adopt the group’s causal attributions. Our research engaged this perspective and sought to combine attribution theory with social identity theory to understand the attributions individuals make about the determinants of obesity. We employed data from a 2006 random sample national survey of adults as well as a unique 2013 survey of American adults to examine whether partisan and weight-based identities influence the likelihood of making biological attributions about obesity and whether these attributions, along with the relevant identities, continued to shape policy preferences related to attempts to reduce obesity in society. Our analyses allow us to draw several important conclusions. First, our results support our linkage between attribution theory and identity theory by indicating that partisanship and weight-based identity influence the likelihood of making a particular attribution. We demonstrated that Republicans are more likely to attribute being 21 overweight to individual lifestyle choices while overweight individuals are more likely to attribute being overweight to biology or genetics. In particular the powerful role of partisan identities is consistent with existing theory and empirical evidence about attributions (HaiderMarkel and Joslyn 2008; Joslyn and Haider-Markel 2012; Weiner et al. 2011). Second, attributions shape emotions towards overweight people. Those making lifestyle choice attributions for obesity were more likely to have more negative feelings towards the obese, more likely to unsympathetic, and more likely to feel actual anger. IN turn we provided evidence that attributions shape support for hiring discrimination towards obese people, both directly, and indirectly, through shaping emotions towards these individuals. Third, attributions for obesity are powerful predictors of support for discrimination by private companies; those who attribute obesity to biology are significantly less likely to support hiring discrimination by private firms. And partisans differ here as well; Republicans were significantly more likely to support private discrimination of obese individuals than were Independents or Democrats, even controlling for attributions. Finally, our analysis revealed that gender and education do not predict attributions or policy support precisely as we expected. Indeed, our analysis highlights the need for more precise measures of attributions for obesity as well as additional measures of policy preferences. Implicit in our findings is the notion that individuals might also make contextual attributions that may or may not be outside of the control of individuals. We believe that additional research, and more precise survey questions, can better capture the nuances of how obesity, and its causes, has become politicized and how attributions about obesity help to shape the potential policy solutions to what is a documented health epidemic. 22 Methodological Appendix A probability sample of 1,596 subjects were recruited by Research Now to participate in a study measuring political attitudes. The study was fielded from June 18-June 21, 2013 Members of the panel complete an extensive member profile survey before they are selected to participate in a particular research project. In addition, Research Now employs a digital fingerprinting technology that prevents more than one person from completing a survey from the same computer, and they use Geo-IP validation to ensure that the computer used matches the geographic location of the survey respondent. Participants are recruited using the eRewards invitation only methodology. Those who have not received an invitation to participate via email, are blocked from participation in the survey. The AAPOR response rate to this study was 11.87%. The demographic characteristics of this panel closely resemble that of the United States population on several important traits. Table A.1 displays the demographics of this sample compared to MTurk samples (adapted from Berinsky, et al. 2012) and the Annenburg National Election Study (Johnston, et al. 2008). Survey Demographics Demographics Female Age (mean years) Education (% completing some college) White Black Asian Latino (a) Multi-Racial Party Identification Democrat Independent Republican N June 2013 survey 51.65% 50.5 31.43% MTurk 60.1% 20.3 - NAES 2008 56.62% 50.05 62.86% 80.9% 5.31% 5.25% 4.95% 2.71% 83.5% 4.4% - 79.12% 9.67% 2.53% 6.3% 2.37% 31.98% 41.18% 26.85% 1,596 40.8% 34.1% 16.9% 484-551 36.67% 20.82% 30.61% 19,234 23 References Atkeson, Lonna Rae, and Cherie D. Maestas. 2012. Catastrophic Politics: How Extraordinary Events Redefine Perceptions of Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bartels, Larry M. 2002. "Beyond the Running Tally: Partisan Bias in Political Perceptions." Political Behavior 24 (2):117-50. Baumeister, Roy F., and Leonard S. Newman. 1994. Self-Regulation of Cognitive Inferences and Decision Processes. Personal and Social Psychology Bulletin 20(1):3-19. Berinsky, Adam J. 2009. In Time of War: Understanding American Public Opinion from World War II to Iraq. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Berinsky, Adam J., Gregory A. Huber, and Gabriel S. Lenz. 2011. "Using Mechanical Turk as a Subject Recruitment Tool for Experimental Research." http://web.mit.edu/berinsky/www/files/MT.pdf: Working Paper Brandt, Mark J. 2012. “Onset and Offset Deservingness: The Case of Home Foreclosures.” Political Psychology 34(2):221-238. Brown, Adam R. 2010. "Are Governors Responsible for the State of the Economy? Partisanship, Blame, and Divided Federalism." The Journal of Politics 72 (3):605-15 Diemer, M. A., Mistry, R. S., Wadsworth, M. E., López, I. and Reimers, F. 2013. “Best Practices in Conceptualizing and Measuring Social Class in Psychological Research.” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 13: 77–113. Evans, Geoffrey, and Robert Anderson. 2006. "The Political Conditioning of Economic Perceptions." The Journal of Politics 68(1):194-207 24 Gaines, Brian J., James H. Kuklinski., Paul J. Quirk., Buddy Peyton., and Jay Verkuilen. 2007. “Same Facts, Different Interpretations: Partisan Motivation and Opinion on Iraq.” The Journal of Politics 69(4):957-974. Gerber, Alan. S., and Gregory A. Huber. 2010. “Partisanship, Political Control, and Economic Assessments.” American Journal of Political Science 54(1):153–173. Gomez, Brad T., and J. Matthew Wilson. 2003. "Causal Attribution and Economic Voting in American Congressional Elections." Political Research Quarterly 56:271-82. Gomez, Brad T., and J. Matthew Wilson. 2008. "Political Sophistication and Attributions of Blame in the Wake of Hurricane Katrina." Publius: The Journal of Federalism 38(4): 633-50. Green, Donald, Bradley Palmquist, and Eric Shickler. 2002. Partisan Hearts and Minds: Political Parties and the Social Identities of Voters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Griffin, W.E., and Y. Oheneba-Sakyi. 1993. “Sociodemographic and Political Correlates of University Students’ Causal Attributions for Poverty.” Psychological Reports 73(6):795-800. Gilligan, Carol. 1982. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Haider-Markel, Donald P., and Mark R. Joslyn. 2008. “Understanding Beliefs about the Origins of Homosexuality and Subsequent Support for Gay Rights: An Empirical Test of Attribution Theory” Public Opinion Quarterly 72(2):291-310. Haider-Markel, Donald P., Mark R. Joslyn, and Matt Miles. 2013. “Who Can Succeed in the 25 ‘New Normal’?: Social Identities and Attributions about Success.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, IL. Harsanyi, David. 2007. Nanny State: How Food Fascists, Teetotaling Do-Gooders, Priggish Moralists, and Other Boneheaded Bureaucrats Are Turning America into a Nation of Children. New York: Random House. Hellwig, Timothy, and Eva Coffey. 2011. "Public Opinion, Party Messages, and Responsibility for The Financial Crisis in Britain." Electoral Studies 30 (3):417-26. Heyman, Gail D., and Susan A. Gelman. 2000. "Preschool Children's Use of Trait Labels to Make Inductive Inferences." Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 77(1): 1-19. Hibbing, John R., and Elizabeth Theiss-Morse. 2001. What is it About Government that Americans Dislike? Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. Horwitz Allan V. 2005. “Media Portrayals And Health Inequalities: A Case Study Of Characterizations Of Gene X Environment Interactions.” Journals of Gerontology Series B. 60(2):48–52 Jones, Edward E., David E. Kanhouse, Harold H. Kelly, Richard E. Nisbett, Stuart Valins, and Bernard Weiner. 1972. Attribution: Perceiving the Causes of Behavior. New York: General Learning Press. Joslyn, Mark R., and Donald P. Haider-Markel. 2012. “The Politics of Causes: Mass Shootings and the Cases of the Virginia Tech and Tucson Tragedies” Social Science Quarterly 94(2):410-23. Keller, Johannes. 2005. "In Genes We Trust: The Biological Component of Psychological 26 Essentialism and Its Relationship to Mechanisms Of Motivated Social Cognition." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 88(4): 686-702. Kruglanski, Arie W. and Donna M. Webster. 1996. “Motivated Closing of the Mind: “Seizing” and “Freezing.”” Psychological Review. 103(2):263-283. Kunda, Ziva. 1990. “The Case for Motivated Reasoning.” Psychological Bulletin 108(3): 480-498. Layman, Geoffrey C., Thomas M. Carsey, and Juliana Menasce Horowitz. 2006. “Party Polarization in American Politics: Characteristics, Causes, and Consequences.” Annual Review of Political Science 9(1):83-110. Levy, Sheri R., Steven J. Stroessner, and Carol S. Dweck. 1998. "Stereotype Formation And Endorsement: The Role Of Implicit Theories." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74(6): 1421-36. Lord, Charles G., Lee Ross, and Mark R. Leeper. 1979. “Biased Assimilation and Attitude Polarization: The Effects of Prior Theories on Subsequently Considered Evidence.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37: 2098-2109. Maestas, Cherie D., Lonna Rae Atkeson, Thomas Croom, and Lisa A. Bryant. 2008. "Shifting the Blame: Federalism, media, and public assignment of blame following Hurricane Katrina." Publius: The Journal of Federalism 38(4): 609-632. Malhotra, Neil. 2008. "Partisan Polarization and Blame Attribution in a Federal System: The Case of Hurricane Katrina." Publius: The Journal of Federalism 38 (4):651-70. Malhotra, Neil, and Alexander G. Kuo. 2008. "Attributing Blame: The Public’s Response to Hurricane Katrina." The Journal of Politics 70 (1):120-35. Marsh, Michael, and James Tilley. 2009. "The Attribution of Credit and Blame to Governments 27 and Its Impact on Vote Choice." British Journal of Political Science 40:115-34. Peffley, Mark, and John T. Williams. 1985. "Attributing Presidential Responsibility for National Economic Problems." American Politics Quarterly 13 (3):393-425. Pellegrini, R.J., S.S. Queirolo, V.E. Monarrez and D.M. Valenzuela. 1997. “Political Identification and Perceptions of Homelessness: Attributed Causality and Attitudes on Public Policy.” Psychological Reports 80:1139-1148. Rothbart, M., and Taylor, M. 1992. “Category labels and social reality: Do we view social categories as natural kinds. In G. R. Semin & K. Fiedler (Eds.), Language and social cognition (pp. 11–36). London: Sage. Rudolph, Thomas J. 2003a. "Institutional Context and the Assignment of Political Responsibility." The Journal of Politics 65 (1):190-215. Rudolph, Thomas J. 2003b. "Who’s Responsible for the Economy? The Formation and Consequences of Responsibility Attributions." American Journal of Political Science 47 (4):698-713. Rudolph, Thomas J. 2006. "Triangulating Political Responsibility: The Motivated Formation of Responsibility Judgments." Political Psychology 27 (1):99-122. Sibley, C. G. and Kurz, T. 2013. “A Model of Climate Belief Profiles: How Much Does It Matter If People Question Human Causation?” Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy. 13(1): 245–261. Suhay, Elizabeth, and Toby Epstein Jayaratne. 2012. “Does Biology Justify Ideology? The Politics of Genetic Attribution.” Public Opinion Quarterly 77(2):497-21. 28 Taber, Charles S., and Milton Lodge. 2006. “Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs.” American Journal of Political Science 50: 755-769. Tetlock, P.E. 1985. Accountability: A social check on the fundamental attribution error. Social Psychological Quarterly. 48, 227-236. Tilley, James, and Sara B. Hobolt. 2011. "Is Government to Blame? An Experimental Test of How Partisanship Shapes Perceptions of Performance and Responsibility." The Journal of Politics 73 (2):316-30. Weiner, Bernard, Danny Osborne, and Udo Rudolph. 2011. “An Attributional Analysis of Reactions to Poverty: The Political Ideology of the Giver and the Perceived Morality of the Receiver.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 15(2):199-213 Williams, Steve. 1984. “Left-Right Ideological Differences in Blaming Victims.” Political Psychology, 5(4):573-581. Winter, L., and Uleman, J.S. 1984. “When are social judgments made? Evidence for the spontaneousness of trait inferences.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 237-252. Wlezien, Christopher, Mark Franklin, Daniel Twiggs. 1997. “Economic Perceptions and Vote Choice: Disentangling the Endogeneity.” Political Behavior 19(1):7-17. Worden, Alissa Pollitz. 1993. “The Attitudes of Women and Men in Policing: Testing Conventional and Contemporary Wisdom.” Criminology 31 (2): 203–41. Yzerbyt, Vincent., Charles M. Judd, and Oliver Corneille. Eds. 2004. The Psychology Of Group Perception: Perceived Homogeneity, Entitativity, and Essentialism. New York: Taylor & Francis. 29 Zucker, G.S., and Bernard Weiner. 1993. “Conservatism and Perceptions of Poverty: An Attributional Analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 23(6):925-943. 30 Table 1. Predicting Attributions for Obesity and Related Policy Preferences. Overweight Because of Genetics Companies can refuse to hire Genetic Attribution ----- -.720** (.211) Republican -.402** (.166) .401** (.153) -.204 (.197) -.003 (.152) .134 (.078) .076 (.052) .427** (.125) -.548** (.123) .432* (.182) -.859** (.125) .297** (.066) .130** (.041) -1.618** (.388) -2.498** (.340) Independent Variables Overweight White Female Education Age Constant/cut 1 Fast Food Legally Responsible Favor Gov’t Regulations on Fat Favor Extra Tax on Fat Food .151 (.139) .098 (.138) -.034 (.142) -.836** (.103) -.192* (.096) -.187 (.130) -.126 (.097) -.047 (.051) -.037 (.033) -.787** (.100) -.213* (.093) -.158 (.127) .271** (.094) -.072 (.049) -.086** (.031) -.839** (.101) -.167 (.096) .122 (.129) .110 (.095) .216** (.050) -.056 (.032) -1.645 -2.655 -.553 /cut 2 .496 -1.136 1.145 /cut 3 2.500 1.012 2.868 Log Likelihood -610.653 -829.358 -1765.896 -1993.647 -1928.487 Pseduo R-square .02 .08 .03 .03 .04 Chi Square 19.32 151.03 90.79 108.61 151.35 Notes: Coefficients are Logistic and Ordered regression coefficients; standard errors are in parentheses. ** p < .01, * p < .05. The data are from a June 2013 random sample survey of American adults conducted for the authors by Research Now. 31