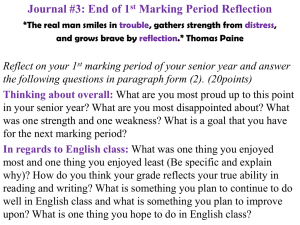

Understanding assessment

advertisement