Women who cross borders - black magic?

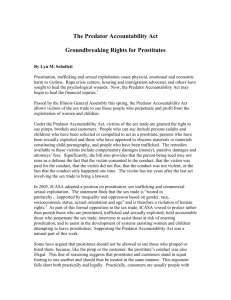

advertisement