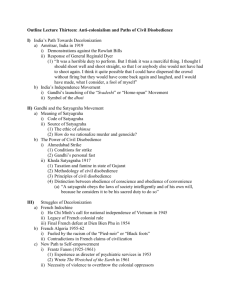

A Jurisprudential analysis of Civil Disobedience in South Africa

advertisement