Nov 2013 - Supervisor of Salvage and Diving

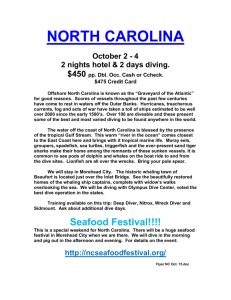

advertisement