the inner strength of women in khali̇d husseini's a thousand

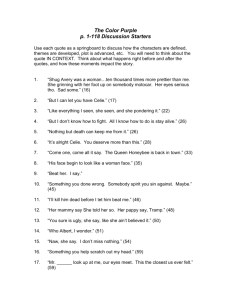

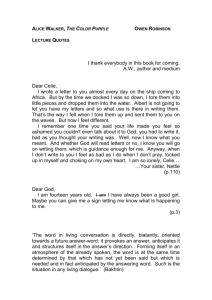

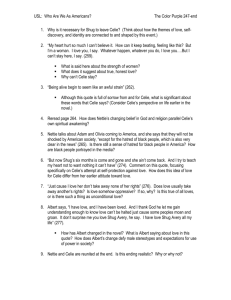

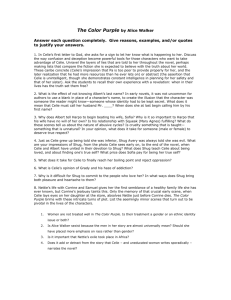

advertisement