MELTON-THESIS - OAKTrust Home

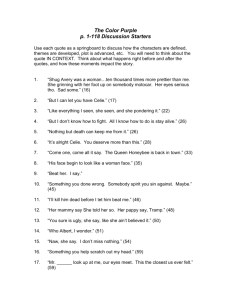

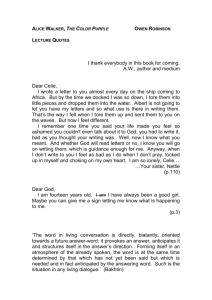

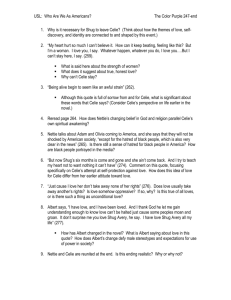

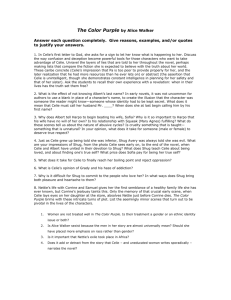

advertisement